It’s not hard to find close elections.

In 2015, a Mississippi state house race ended in a tie, after which the winner was decided by drawing straws. A 2013 mayoral race in the Philippines was deadlocked and resolved with a coin toss. A 2013 legislative election in Austria was decided by a single vote, after wrangling over the validity of a ballot featuring a vulgar cartoon. Heck, I didn’t have to look far to find examples: In 1990, my own uncle lost his bid for Congress by less than 1 percent of the vote.

But there is one election that is so consistently close, and so important, that it deserves special consideration—the United States presidential election.

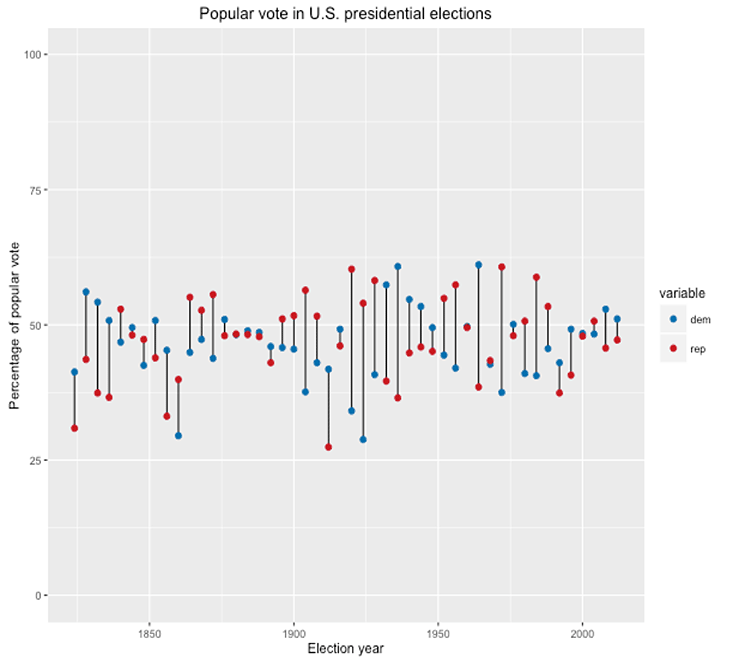

I plotted the top two popular vote-getters in every U.S. presidential election since 1824, using data from The American Presidency Project. The top two contenders, typically a Democratic and a Republican, but occasionally a Whig, have danced closely around the 50-50 mark for nearly 100 years. Only four times since 1824 has the winner received more than 60 percent of the popular vote. Since 2000, the candidates have been separated by an average of 3.5 points. The median and average separations have been 8.2 and 9.5 points since 1824—a figure skewed upward due to a few outlying and not particularly close races. (The electoral tally doesn’t usually appear so close because the Electoral College tends to magnify differences in the popular vote.)

This is a feature of U.S. politics that many of us have become accustomed to. So is it unsurprising? Not really. “Considering all of the factors that go into what would make an election close or not close—incumbency, the brand of the parties—my perspective is that there’s a surprising rate of close elections,” Eitan Hersh, a Yale political scientist and the author of Hacking the Electorate: How Campaigns Perceive Voters, told me.

The question is, why?

In September 2012, the Mitt Romney campaign was gasping its last breaths in an ultimately unsuccessful race to unseat the incumbent President Barack Obama. The journalist Matt Taibbi took to the pages of Rolling Stone to lament that the race was even as close as it was. He attributed that fact in part to “the power of our propaganda machine.” That machine, of course, is the bullhorned news media.

The machine, Taibbi continued, “has conditioned all of us to accept the idea that the American population, ideologically speaking, is naturally split down the middle, whereas the real fault lines are a lot closer to the 99-1 ratio the Occupy movement has been talking about since last year.” The media, Taibbi was suggesting, was partly responsible for ginning up close races where they shouldn’t otherwise exist.

The media’s incentives to tout a close race seem obvious: A close race brings high drama. High drama brings eyeballs. Eyeballs bring subscribers and ad revenue. Rinse and repeat. I asked David Yepsen, director of the Paul Simon Public Policy Institute at Southern Illinois University, Carbondale, about this theory. For 34 years and nine presidential campaigns, Yepsen covered politics for The Des Moines Register.

Yepsen agrees that media attention can drive a race toward the 50-50 point. “Reporters, if they see a good race for an important office, will write about it,” he says. “And all of a sudden people are paying more attention and the race can tighten up.” But media can also have the opposite effect. Reporters may quickly kiss off a third-party candidate, for example, who doesn’t seem to stand a chance, thereby giving her even less of a chance. So media coverage can cut both ways. “Some of this is chicken or the egg,” Yepsen says.

Perhaps the U.S. presidential election is usually close simply because so many Americans are constantly dissatisfied with the status quo.

Besides, media isn’t the only party interested in making a race look close. In partnership with state Democratic parties and the 2012 Obama campaign, Hersh surveyed political insiders involved in presidential campaigns about how they thought their candidate would do. It turned out they thought races were closer than they were. Incumbents, who generally win and by a lot, think their races are going to be closer than they are. Challengers, who often have no shot, also think they’re going to be closer. “Very few people are willing to admit that they’re probably going to lose,” Hersh says.

In other words, the politicians themselves push voters and each other to believe in a close race. “You don’t need the media narrative to get you there,” Hersh says.

There are other forces in play that could favor close elections. In congressional (as opposed to presidential) races, winning margins can be driven down by the uniquely American practice of gerrymandering districts. This is a process by which district boundaries are redrawn to the advantage of one political party. In general, parties will want to draw these boundaries so as to give the most seats to their side. But in so doing, giving a candidate with a cushy advantage in a safe district even more votes is essentially wasting those votes. A more efficient way to gerrymander is to create many districts that favor your party by slim (even uncomfortably slim) majorities, so you can rack up more seats with the same number of voters. This, in turn, can create close races when there wouldn’t otherwise have been one.

The relevance of gerrymandering to the U.S. presidential election, however, is tenuous at best. Only two U.S. states use congressional districts to decide on electoral college votes (Maine and Nebraska), and it’s not clear whether the impression of closeness in a congressional race impacts voter psychology in the presidential race.

Perhaps the U.S. presidential election is usually close simply because so many Americans are constantly dissatisfied with the status quo. But Hersh isn’t convinced by that either. “There’s no reason they should see it all the time,“ he explains. “If they saw it all the time, it would suggest something crazy, like all their incumbents do a bad job.” On the other hand, regularly close elections could indicate a lack of engagement, and a lack of real policy alternatives available to voters. Voter engagement as measured via turnout of the eligible population, however, has reached as high as over 60 percent in 2008, and job approval ratings for outgoing presidents have been as high as 66 percent, in the case of Bill Clinton. These sentiments were not sufficient to avoid yet another close election in 2000.

None of these theories seem to squarely hit the mark. But there is another candidate explanation, and it is one that nearly every expert that I talked to zeroed in on: the median voter theorem.

The U.S. holds federal elections using a first-past-the-post system, in which voters vote for one candidate for a given office, and the candidate who receives more votes wins. It’s an approach that tends to create strong two-party systems—in our case, it’s donkeys vs. elephants, with third parties making only small and infrequent splashes in the pool of American democracy. This is an old idea called Duverger’s Law. (That’s Maurice Duverger, a French sociologist and politician, who died in 2014.)

This law, in turn, allows us to invoke the ice cream parable.

Imagine a long, straight boardwalk on a sunny summer day, running alongside a beach that is everywhere packed with sunbathers. Two ice cream vendors, each with a movable ice cream stand, compete for the boardwalk’s humming business. They both arrive at the beach as the temperature is spiking and the would-be customers are clamoring, and must decide: Where to set up shop?

Suppose one vendor decides to set up at the eastern terminus of the boardwalk. The other, seasoned from many long summers of ice cream vending, sets up just a bit to his west, being thus closer to and more convenient for the vast majority of the sunbathers, stealing the bulk of the first vendor’s business. The first vendor is not at all pleased with this new arrangement, and so moves a bit to his competitor’s west, retaking much of the business. The competitor is similarly displeased, moves to the west again, and on and on the ice cream vendors’ dance goes, until both set up shop as close as possible to the boardwalk’s center. There, they split the beach’s business, and neither can profitably steal any of the other’s customers. They are, a game theorist would say, in equilibrium.

“Each party strives to make its platform as much like the other’s as possible.”

That is, in thin guise, the median voter theorem. The two ice cream vendors are politicians. The sunbathers are voters. And the boardwalk is the left-right political spectrum. By positioning themselves along the allegorical boardwalk, presidential candidates are adopting a policy platform—a political position, somewhere between left and right extremes. A voter prefers the candidate with the political position closest to her own, just as the sunbather prefers the closest ice cream. The outcome, this theory predicts, is that both candidates adopt centrist positions and split the vote essentially down the middle. Et voilà: a close election.

The median voter model is, of course, a somewhat brutish abstraction—a workhorse model of mid-level college courses in microeconomics or formal political theory. It ignores aspects of politicians beyond ideology (like personality) and it ignores politicians’ incentives beyond winning (like party loyalty). But it’s illustrative, an animating story, and a useful structure in which to ponder an electoral magnet sitting at the 50-percent mark, drawing in candidates.

The model dates to the work of the mathematician Harold Hotelling, later formalized by the economist Duncan Black and popularized by the economist Anthony Downs. Hotelling’s brief aside in 1929 was the paragraph that launched a thousand political science careers:

The competition for votes between the Republican and Democratic parties does not lead to a clear drawing of issues, an adoption of two strongly contrasted positions between which the voter may choose. Instead, each party strives to make its platform as much like the other’s as possible. Any radical departure would lose many votes, even though it might lead to stronger commendation of the party by some who would vote for it anyhow.

If you move to a far end of the beach, a few folks there will thank you for the ice cream. But you’ll have lost many customers along the way. A century later, the theory remains as powerful as it was then. “Over time, the competitive pressures of the two-party, first-past-the-post system inevitably encourage the two parties to find a coalition that makes them competitive,” Andrew Hall, a Stanford political scientist, told me. The median voter theorem is the On the Origin of Species of elections.

The theory has considerable explanatory power. We often find liberal Republicans in the generally liberal Northeast, and conservative Democrats in the generally conservative South. These are parties and candidates locating near the center of their own specific beaches. The economist Tyler Cowen has argued that the median voter tends to get what he or she wants, even if those things are very expensive—like Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid—and regardless of whether a Democrat or a Republican is in office. And a well-known 1980 paper by the economist Randall Holcombe leveraged data from 257 Michigan school districts, finding that the median voter model accurately predicted educational expenditures. Holcombe concocts theoretical expenditures, based on median voter ideas, and compares them to actual expenditures, and finds that the difference between the two, in the average district, is less than 3 percent regardless of the party in power. He writes: “The theoretical median voter model provides a good explanation of empirical reality.”

Median-voter strategy can also explain some of our recent presidential election. At the start of the 2012 presidential race, Romney and Obama were running combative, pugilistic campaigns—80 percent or more of both campaigns’ advertisements were negative. Romney was being criticized for shipping jobs, and parking his money, overseas, while Obama was being criticized for not giving small business owners their due. Typical stuff, really. But by the presidential debates, the two candidates often found themselves in agreement. On corporate and individual tax rates, energy production, the importance of education and of community colleges, market regulation, health care costs, certain deportations, the pursuit of al-Qaida, an approach to Iran’s nuclear program, and the need for the country to “move forward,” the two candidates had travelled to the center of the beach over the year-long campaign. The two were playing it centrist—“pussyfooting,” as Hotelling put it 90 years ago.

On and on the ice cream vendors’ dance goes, until both set up shop as close as possible to the boardwalk’s center. There, they split the beach’s business.

The median voter theorem can’t account for everything, however. There a dimension beyond policy—and therefore beyond the median voter theorem—to presidential elections. It’s what political scientists call “valence,” and it refers broadly to the dimension of personality, including things like competence, trustworthiness, likeableness, and—much-discussed in 2016—temperament. These are arguably more important in an executive position like president than in a legislative position like representative, where a candidate is vying to be just one member of a larger body.

The ability of a candidate to tweak his or her valence is, typically, less than their ability to tweak a campaign platform. Therefore, if valence dominates an election, the median voter theorem would seem to diminish in importance. “Candidates are obviously way more than just their positions,” says Hall. “When you start to incorporate that into a median-voter-like model, things become much more complicated.” The louder the din of personality and valence in the election, the weaker the median voter theory becomes—and, presumably, the less reason we have to expect a close election.

What’s remarkable, though, is that even in elections where valence dominates, poll numbers can remain close. Like, for example, in the election about to be held.

This November, valence is loud indeed. As a presidential candidate, Trump seems sui generis—at least since the likes of segregationist populist George Wallace, another outspoken character who led in polls but lacked the blessing of his party. This year’s contest is also unique because valence is arguably its defining dimension. The personalities of the two candidates could not be more different, one often sounding more like a shock-jock than a traditional candidate and the other a lifelong politician with whom many voters have trust issues.

Also, Trump is not acting like a rational ice cream seller. He has not appeared to move his policy portfolio, to the extent he has one, toward the center. “Rational candidates end up pivoting, and trying to move as much as they can back toward the center. But of course right now there’s one presidential candidate who’s not doing that at all,” Tom Vogl, a Princeton economist, told me.

Nevertheless, this race remains fairly close, tightening with just days until Election Day. It’s currently projected to be twice as close as the average popular vote margin separating presidential candidates over the past 200 years. As I write, FiveThirtyEight estimates that the two candidates are separated by 3.5 percent in the popular vote. Even in this most unusual of elections, which has defied precedent and prediction on a daily basis, there seems to be a gravitational force cutting through the noise, pulling the race to its 50-50 knife’s edge.

So if we accept the notion that, in 2016, we’ve left the one-dimensional world of the classical median voter theorem, we can ask ourselves the question anew: Why is this race close? Some possibilities spring to mind. Perhaps the historically negative perceptions of the candidates by voters happen to be nearly perfectly canceling each other out by chance. Perhaps the candidates’ particular clashing personalities exist in a sort of tenuous electoral stasis. Or, maybe valence is overestimated, and some form of the median voter theorem still applies, with voters taking the standard positions of the two parties as default. (There’s been precious little serious talk of new policy in this race, after all.) Or, perhaps, there is a thorny game being played between the candidates, a satisfactory model of which we haven’t yet understood—the median voter theorem in multiple dimensions.

Whatever the case may be, this outlying campaign will be debated and dissected in lecture halls and journals for years to come. “I think the campaign will draw more scholars of American politics to the topic of populism,” says Hersh. And, perhaps, it will spur new ideas on the interplay and relative importance of policy, valence, the median voter, and close elections. In that sense, one thing is sure: punditry and political science will have to change, at least a bit, to account for it.

Oliver Roeder is a senior writer at FiveThirtyEight.