There’s a lot of talk in this country about the federal deficit,” then-Senator Barack Obama said in a 2006 commencement address at Northwestern University. “But I think we should talk more about our empathy deficit.” What we need, he said, was the ability to “see the world through those who are different from us.”

Since Obama’s speech, the phrase “empathy deficit” has gained a foothold, appearing everywhere from academic journals to mainstream media outlets. Among the varied responses to the 2016 United States presidential election were calls for a greater general empathy. Many liberals tried to peer across party lines to understand the motivations of Donald Trump voters, for instance interviewing Republican constituents and reading books about rural poverty (think J.D. Vance’s Hillbilly Elegy or Arlie Hochschild’s Strangers in Their Own Land). But these efforts didn’t alleviate tension between parties, which might be because empathy-building efforts don’t always work. They can even backfire in some cases: when people take the perspective of someone they think will act selfishly, they act more selfishly themselves.1 If empathy deficits fuel social divisions, why doesn’t empathy building salve them?

Maybe the problem is not with the remedy, but with the diagnosis. Empathy is not like the volume knob on a stereo, which tunes all frequencies of a piece of music identically; it’s more like an equalizer, which boosts different frequencies by different amounts. Rather than empathizing more or less overall—and changing the quantity of a single empathy deficit—we tune our empathy, boosting it for some while lowering it for others. Even people who empathize a lot can still suffer from an empathy imbalance—greater empathy for people who look, think, and act like themselves (their ingroup) and reduced empathy for those who don’t (their outgroup).

Research suggests that imbalances can be a bigger problem than deficits. This year, psychologists Emile Bruneau, Mina Cikara, and Rebecca Saxe measured the empathy in three ingroup-outgroup pairs: Americans versus Arabs, Greeks versus Germans, and Hungarians versus refugees. They found that people who empathized more with their ingroup than outgroup—an empathy imbalance—held more negative attitudes toward outsiders, and even a willingness to harm them. In fact, a person’s imbalance mattered more than their overall level of empathy.2

Conflict resolution programs designed to increase overall empathy could backfire if they increase ingroup empathy in an already imbalanced situation. The more empathy someone feels for their ingroup, the more damage they might be willing to inflict to protect it. The people who are most bound to their own group also tend to be the most biased, unwilling to consider information distasteful to their group’s preference. In one study, psychologist Geoff Cohen showed that in evaluating new laws, people care more about which political party proposed it than the content of the law. What’s more, people aren’t aware of this tendency and maintain that their evaluation reflects personal beliefs and an objective assessment of policy content.3

The best response to social divisions may sometimes involve doing something counterintuitive: lowering empathy for our ingroup and distancing from our own kind.

But is this even possible?

Although they may be less apparent, there have also been episodes of ingroup de-empathizing that address empathy imbalances rather than deficits. In January 2017, U.S. senators John McCain and Lindsey Graham publically criticized Trump’s travel ban preventing people from seven Muslim-majority nations from entering the U.S., calling it a “self-inflicted wound” in the fight against terrorism. McCain, who has since been crowned “Critic in Chief” by The New York Times, frequently condemns Trump: He pushed back when Trump called the U.S. military raid in Yemen “a huge success,” and when Trump suggested the U.S. and Russia were moral equals. Despite being a lifelong Republican, McCain regularly speaks out against his own party.

People can ignore the instinct to follow the crowd—particularly if someone already has.

There are similar stories on the left. After Trump’s election, the Anti-Facist (Antifa) movement resurged and, in February, stoked violence while protesting Milo Yiannopolous’s speech at the University of California, Berkeley, breaking windows and launching fireworks at campus buildings. Liberals quickly distanced themselves in response, asserting that this outburst undermined their values. In condemning the edge of their own party, they extended an olive branch across party lines.

Researchers call these acts “emotional compensation:” adjusting one’s own feelings to balance out those of their peers when a person feels their group has gone emotionally awry. For instance, the psychologist Amit Goldenberg finds that individuals express more guilt at social injustice if they see their group as too comfortable with it. He and his colleagues presented Jewish Israelis with a news story about a Palestinian girl who was deported under a new immigration law. He told some people that other Israelis felt little guilt, and others that their group felt a lot of it. The less guilty their group seemed, the more guilt they felt individually.4

Rejecting the feelings or actions of one’s own group also plays a role in whistleblowing. The psychologists Adam Waytz, James Dungan, and Liane Young argue whistlebowing involves a tradeoff between the desire to be fair and the desire to be loyal. These desires clash when an ingroup does something a member deems unethical. Waytz and colleagues asked individuals to write essays about the importance of fairness or of loyalty, then perform an unrelated group-based task (in which they wrote out the numbers 1 to 30 in English). At the end of the experiment, participants were given an opportunity to inform the researchers about a fellow participant’s rule breaking during the task. People who wrote about valuing fairness were more likely to report on ingroup rule breaking, while people who wrote about valuing loyalty were more likely to let bad behavior slide.5

Waytz, Dungan, and Young suggest that institutions should promote fairness norms—just and ethical treatment of all persons and groups—and even try to redefine loyalty among members to include the reporting of unethical behavior. This way, whistleblowing—and, potentially, other kinds of emotional compensation—could come to be seen as a pro-group behavior done to preserve a group’s integrity instead of an act of betrayal. Internal disagreement can even come to be celebrated. The American Foreign Service Association, for example, honors employees with Constructive Dissent Awards for challenging departmental policies in non-public forums.

It can be hard to distance one’s self from one’s own group, but ingroup de-empathizing is not just possible—it is common. When used right, it helps resolve conflict when traditional methods fall short, and can encourage groups to engage in a wider self-reflection.

Individuals express more guilt at social injustice if they see their group as too comfortable with it.

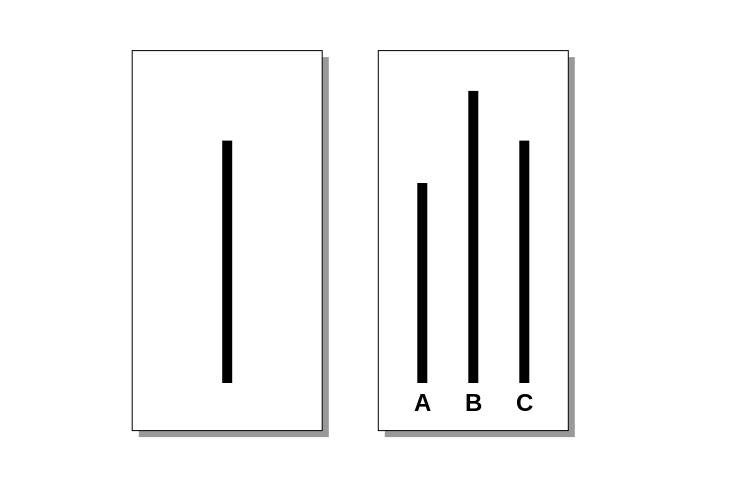

In a famous series of experiments on conformity in the 1950s, psychologist Solomon Asch demonstrated people’s extraordinary sensitivity to social influence in deciding on truth claims. Asch assembled a group consisting of study participants mixed with research staff pretending to be study participants. He then asked them to decide whether a set of lines had the same length or not. When the research staff pretended to believe that two lines of different size were actually equal in length, the real participants tended to agree with them, doubting their own judgment. In Asch’s experiments, 75 percent of participants agreed with an incorrect answer at least once.6

In further studies, Asch showed that such conformity is not inevitable, and people can ignore the instinct to follow the crowd—particularly if someone already has. When the research staff pretending to be regular participants were not in unanimous agreement, it made it easier for participants to resist the pull of the group, and considerably reduced rates of conformity. Courage is contagious, and when one person speaks out against their group others follow suit. Inside every group member is a potential lone dissenter who can restore a sense of individuality and create a foundation for constructive dissent.

Though it’s not easy, distancing ourselves from our own ingroups can help one person become a few people, a few people become a group, and a group become a movement. And that can make all the difference.

Erika Weisz is a doctoral candidate in the Stanford Social Neuroscience Lab. She studies motivations that drive people toward or away from empathy, and develops empathy-building interventions.

Jamil Zaki is a professor of psychology at Stanford University and the director of the Stanford Social Neuroscience Lab. He has written about psychology and neuroscience for The New York Times, The Wall Street Journal, thenewyorker.com, The Atlantic, Nautilus, Scientific American, Wired, and The Huffington Post. He is currently at work on a book, Choosing Empathy, which focuses on building empathy under difficult circumstances.

References

1. Epley, N., Caruso, E., & Bazerman, M.H. When perspective taking increases taking: reactive egoism in social interaction. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 91, 872–889 (2006).

2. Bruneau, E. G., Cikara, M., & Saxe, R. Parochial empathy predicts the reduced altruism and the endorsement of passive harm. Social Psychological and Personality Science (in press).

3. Cohen, G. L. Party over policy: The dominating impact of group influence on political beliefs. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 85, 808–822 (2003).

4. Goldenberg, A., Saguy, T., & Halperin, E. How group-based emotions are shaped by collective emotions: Evidence for emotional burden and emotional transfer. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 107, 581-596 (2014).

5. Waytz, A., Dungan, J., & Young, L. The whistleblower’s dilemma and the fairness-loyalty tradeoff. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology 49, 1027-1033 (2013).

6. Asch, S.E. Studies of independence and conformity: A minority of one against a unanimous majority. Psychological Monographs 70, 1-70 (1956).

Lead image credit: Bernhard Lang / Getty Images