The first time they met, French artist Françoise Gilot seemed more interested in her salad than in Jonas Salk—somewhat embarrassing for her friend Chantal Hunt, who had insisted she join them for lunch. Chantal’s husband, John Hunt, the executive vice president of the Salk Institute, had invited Salk to their home to discuss “Institute issues.” Gilot had warned Chantal that she was tired from completing the lithograph series at the Tamarind Workshop in Los Angeles, and she needed some rest before returning to Paris. “I’m going to go have lunch at a restaurant,” she told her friend. “I don’t want to see a scientist.” Chantal said she didn’t need to talk. “Fine,” Gilot replied, “I don’t talk.”1

The next evening, Gilot accompanied the Hunts to a black-tie dinner at the Institute. Seated with other artists, she enjoyed herself. Although she didn’t notice Salk, he saw her. Later he told Françoise he found the situation curious. One day she behaved “like a lump,” he said. The next day she was “laughing like I don’t know what.” He wondered, “Who is this person?”1 So he invited Gilot to the Institute for a private tour.

Once there, this woman who had silently looked at her salad two days before began talking with great animation and sophistication, a mixture of self-confidence and femininity. Salk knew almost nothing about art, and Gilot could not converse about science, but they had one common interest, modern architecture. That was a start.

Jonas became enthralled with Françoise. He didn’t know much about her life, except that she was a successful artist, although he had seen none of her paintings, and that she had been Pablo Picasso’s mistress, although he likely had not read her best-selling memoir, Life with Picasso. The past didn’t interest Salk; he was looking to the future.

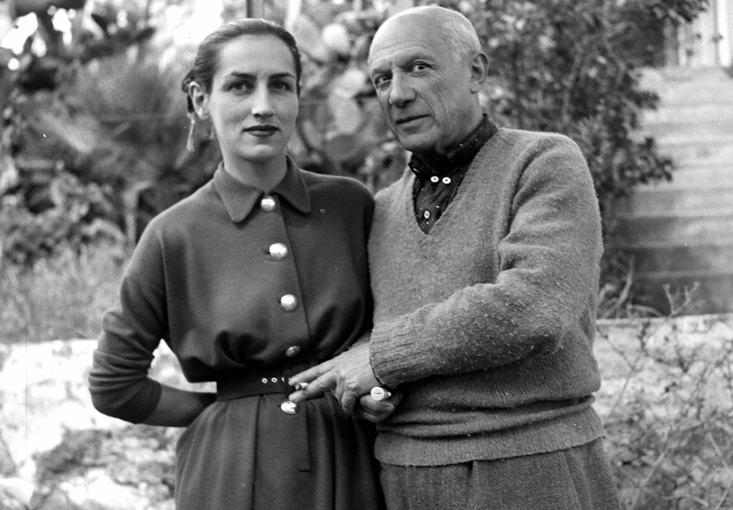

The outbreak of World War II marked a tragic time in Gilot’s life. Every week she learned of comrades who had died participating in the Resistance and Jewish friends who had been deported. She felt an urgency to contribute in some way. “I felt that upholding the cultural values we shared was an individual duty and a necessity.”2 In May of 1943, Françoise had her first exhibition. Around the same time, she met Pablo Picasso. “I believe that if I had met Picasso in normal circumstances, nothing would have happened between him and myself,” she reflected.1

Alain Cuny, a popular actor, had invited Françoise and her friend the artist Geneviève Aliquot to dine at Le Catalan, a Left Bank restaurant frequented by actors and artists. They had just ordered when Cuny pointed out Pablo Picasso. Throughout dinner, Gilot noticed Picasso was staring at their table. Afterward, he brought over a bowl of cherries and asked Cuny to introduce his friends. Cuny told him they were artists. Picasso laughed. “Well, I’m a painter, too. You must come to my studio and see some of my paintings.”3 The first visit, amidst a bevy of admirers, seemed innocuous. But despite their age difference of 40 years, a relationship blossomed, first intellectual, later sexual. “One thing stood out very clearly,” she wrote, “the ease with which I could communicate with him.”3

The past didn’t interest Salk; he was looking to the future.

Those were intoxicating times for Gilot. Picasso introduced her to Alice B. Toklas, Gertrude Stein, and Henri Matisse. Françoise delved into her own work, studying at the École des Beaux Arts. A recent movement called New Realities, in which artists created pure abstract paintings, influenced her, and by 1945 she was gaining notice for her art. In May of 1946, Gilot agreed to move in with Picasso. She learned a lot from him, adopting his work habits. At the same time, she found how difficult he could be. “When he wanted, he was the most charming man,” she told television talk show host Charlie Rose. Yet he had terrible mood swings.

“Why do you always contradict me?” Picasso used to ask her.

“Because it’s a dialogue,” Gilot replied. “Otherwise you can speak to yourself.”1 In the fall of 1953, she took her two children and left. In October of 1969, Gilot traveled to Los Angeles to complete some lithographs. It was on that trip that the Hunts introduced her to Salk.

When Gilot stopped in New York on her way back to Europe, Salk appeared, as if by chance. After that he followed her to Paris, so she invited him to La Galloise for Christmas. “There was no way to find out who bewitched whom,” she told Charlie Rose. “All I can say is that a powerful whirlwind was blowing.”1 Salk found Gilot to be the most alluring and most intellectually engaged woman he had ever known. She had a wonderful laugh, a refreshingly honest way of viewing the world, and the same intensity about her endeavors as he had about his.

Gilot knew Salk’s story from news reports and Richard Carter’s biography, but none of these captured the man behind the public persona. He did not have a typical scientific mind; rather, he seemed to be an intuitive scientist—“an artist in a different field,” she concluded, with a philosophical, almost mystical bent. He cared deeply about his work, not for his own benefit but for mankind’s. People described him as aloof, but she perceived his inherent shyness. “He was always alone,” Gilot observed. “He never had any people to understand him.”

Some thought the attraction had another side. “She was exciting,” Sylvia Salk contended, “because she had been Picasso’s woman.” Beyond any appeal arising from the other’s celebrity status or the physical attraction, however, lay the similar way they approached their work—with unflagging zeal. Passionate about her art, Gilot often worked on 10 to 12 paintings at the same time. And Salk had written in his night notes: “I seem to want to be on 24-hour call in relation to my basic commitment.”4 It appeared to be an excellent match.

Six months after they met, while the sun was setting over Santa Monica Bay, Salk asked Gilot to marry him. She later recounted the scene to Rose in her television interview. When Jonas proposed, she had replied, “A relationship would be all right, but I don’t want to get married.”

“Why not?” he asked.

“Because I don’t want to live with anybody more than six months a year. That’s it. I need my own time to myself, plus I have my children.”

Jonas handed her a piece of paper. “Write down everything that you don’t want,” he directed. “I’ll give you an hour.” Françoise proceeded to write down those elements that would make the marriage unsuitable for her.

Jonas read it over. “Very good. It fits my life perfectly.”

“But we don’t know each other,” she cautioned, “and it may be disastrous because you’re a scientist, and our lives are very far apart.”

“No,” Jonas countered, in what seemed more like a business transaction than a romantic moment, “even if we’re not so happy, at least we’ll be like a citadel; we’ll be a fortress for each other.”

Françoise thought about it. Both felt exhausted by the world and sought a refuge. “In that case, let’s try,” she replied.1

Gilot was 48, an artist, a determined free spirit. Salk was 55, a scientist, averse to conflict. They would live half the year almost 6,000 miles apart. “All our friends on both sides predicted impending doom,” Gilot recalled.

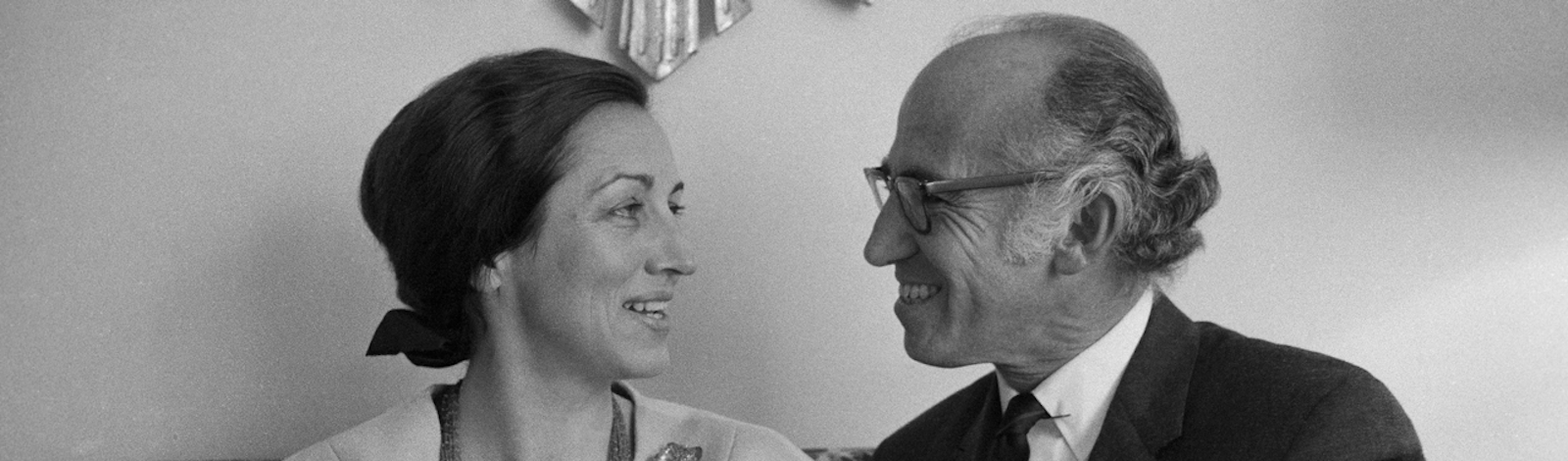

On June 29, 1970, Françoise Gilot and Jonas Salk married in Neuilly-sur-Seine. Françoise wore a simple, stylish dress, and Jonas a dark suit and tie. Gilot’s children, Claude, Paloma, and Aurelia, and Salk’s sons, Peter, Darrell, and Jonathan, attended the wedding, as did Chantal and John Hunt, who had introduced them. Their children met for the first time as their parents prepared to say their vows. Twenty-three-year-old Claude Ruiz-Picasso worked in New York as a photographer for Condé Nast; 21-year-old Paloma was studying jewelry design in Paris; and Aurelia Simon, just 13, attended boarding school. Of Salk’s sons, Jonathan felt the most comfortable, having just spent six months in Paris. Although pleased for their father, whom they had rarely seen so joyous, Salk’s sons must have questioned his impetuousness. He had met Madame Gilot only eight months earlier.

“We did not really know each other well when we got married,” Gilot admitted. They had been together only a few times. “We were more than middle-aged, and the type of love we shared was an adult love, not passion like when you are 18. We understood each other very well, and that was basically the foundation of our union.”

In late August, Françoise, Jonas, and Aurelia returned to La Jolla and moved into a house Salk had rented with spectacular views of the coastline. He could barely wait to introduce—some thought show off—his new wife. “He was absolutely thrilled,” Christine Forester recalled. At a dinner party at the Foresters’ home, Jonas and his new bride danced into the morning hours long after everyone else had collapsed. Forester had never seen him dance more than an occasional waltz. Besides introducing Gilot to friends, Salk also brought her to meet his ex-wife Donna, as if to get her approval. After that, Donna referred to Françoise as her “wife-in-law.”

Just as the media continued to equate Salk with the polio vaccine, it forever linked Gilot with Pablo Picasso. The Harrisburg News, reporting their marriage, identified Gilot as Picasso’s mistress of 11 years. After noting her “discreet wedding” to Salk, the article went on to describe her life with Picasso.5 A Philadelphia Inquirer article about Salk’s work on multiple sclerosis mentioned his marriage to Gilot, “an artist who was the mistress of the late Pablo Picasso.”6

Salk’s childhood had centered on studies, his adulthood on work. He never let exercise, the arts, or leisure distract him. Now that changed. On weekends, he and Gilot went to the La Jolla Beach and Tennis Club to swim or hiked in the nearby hills. They bought season tickets to the Old Globe Theatre. He listened to Schubert and Schumann, enjoyed the opera, even took Aurelia to an occasional musical comedy. He studied French, relaxed at Parisian cafes. As he sailed with Françoise in the Aegean, he learned one could travel for enjoyment. He practiced yoga and meditation, underwent Rolfing, participated in a sensitivity group. Françoise changed his diet, eliminating red meat and lowering the fat and salt content. Within six months, he had lost 25 pounds.

Friends, colleagues, and family noticed major changes in Salk’s appearance. “He was a man who had no inherent taste,” according to Salk’s colleague Jack MacAllister. In an article entitled “Jonas Salk Unfolding,” a journalist described his transformation: “External signs can’t be missed. The suit and ties … have been replaced by dapper, almost mod outfits—ascots, turtlenecks, flared pants, bright ties under dark sport jackets. His hair has grown out in attractive waves.”7 Pictures prior to his marriage show a weary-looking Salk, a bit thick about the middle, in a dark suit and thick glasses, with short-clipped hair—an older version of the man whose face millions knew. Now his hair curled down to his collar; he sported sideburns and wore a scarf tied around his neck. For photos, he held his glasses and perfected a thoughtful, peaceful pose. Sylvia Salk called her brother-in-law “Frenchified.”

“Ours was the union of two very busy people who were completely dedicated to their work, and so it was not the typical husband-wife relationship.”

The media now displayed photographs of Salk with a strikingly beautiful woman at his side. She smiled lovingly as he received the All-India Institute of Medical Science Award, or while President Jimmy Carter put the gold Medal of Freedom around his neck. She donned a fashionable gown to attend an Institute fundraiser, accompanied by Governor Ronald Reagan and his wife, Nancy, along with Steve McQueen and Ali McGraw. At home, Gilot proved to be a gracious hostess, welcoming friends and heightening Salk’s social standing among the resident fellows. “Françoise brought out the lighter side of Jonas,” Maureen Dulbecco observed. “He could be very amusing and enjoy a good laugh.” Gilot often invited her European friends for dinner, providing haute cuisine, fine wine, and stimulating conversation. “It was like a Salk clique,” Christine Forester remarked.

Although Salk’s European colleagues called Gilot “a gracious hostess,” some who worked with him expressed less regard for her. “He married the artist’s concubine,” Don Wegemer sniped. “We used to say, ‘Another Jewish guy has fallen victim to a French woman.’ ” Walter Mack, Salk’s friend from Ann Arbor, also disapproved: “All of a sudden he decided Donna wasn’t good enough. He divorced her and married some French actress.” Salk’s secretary Lorraine Friedman, ever protective of her boss, never understood why he chose Gilot. “She wasn’t particularly interested in being known as Jonas’ wife,” she observed. “She had a life of her own.” Salk’s research associate Fred Westall referred to Gilot as “Picasso’s ex”; nevertheless he considered their marriage a good arrangement. “She needed somebody of the stature of Picasso; she can’t just marry somebody on the street. And he needed someone who was ‘ta-da.’ ” She snubbed Westall on several occasions. “She is the strongest lady I ever met,” he carped. Sylvia Salk thought the newlyweds deserved each other. “She was part of the jet set,” she remarked. “It made his life more exciting. But if they had to live together 365 days a year, I’m sure they never would have made it.”

Jack MacAllister considered these comments unwarranted. He loved the new Jonas: “He grew up in New York poor, and he never had taste. After he married Françoise, he looked younger and more handsome. She brought out a side he didn’t know he had.” MacAllister grew fond of Gilot. Although an intellect, she could be giddy and silly. “It was a whole new world for Jonas,” MacAllister pointed out. “He’d never lived that way. He had lived in a lab. He was a guy in a white coat.” Russell Forester concurred, describing his friend as “1,000 percent happier.”7

His sons noticed the change, too. Jonathan observed that his father seemed delighted to be married. Françoise encouraged his creative side. He started to paint, write poetry; he was living the cosmopolitan life he thought he wanted. “Françoise was more present, involved,” Jonathan maintained, “and clearly, there was a bit of a makeover.” Darrell, on the other hand, thought his father had lost his roots. “Some of it was a little frou-frou,” Jonathan agreed, “but he was happy, and that’s great.”

Before long, the newly married couple began to live apart. “Jonas was a man of his word,” Gilot said. “We were not together year-round.” She spent at least six months in Paris or at her New York studio. “I am not the usual wife. Ours was the union of two very busy people who were completely dedicated to their work, and so it was not the typical husband-wife relationship.” Most viewed it as an unusual arrangement. “When she was there,” one of Gilot’s friends noted, “she really had her attention on being there, being with him, entertaining, doing whatever to be part of that community. But when she wasn’t there, he retreated into his introverted world.” In her absence, Salk resumed his pattern of working incessantly and calling the architect Christine Forester to see what she and her husband Russell planned for dinner.

Although Gilot spent just half the year with her husband, she nonetheless appreciated his diverse facets. “Jonas was many persons in one,” she commented in an interview years after his death. In pursuing science, he used his intuition almost more than rational thought. “Things could be evident to him that were not evident to others, creating a lot of misunderstanding about his thinking. Jonas also had a prophetic side in him regarding the evolution of humankind, and in this, as in many other aspects, he was not well understood.” She described him as self-possessed, never showing irritation or bad temper, even in trying circumstances. She enjoyed his sense of humor, the way he said funny things with a deadpan mien so people couldn’t tell if he was joking. And he was kind. “Many people didn’t see that.” He often appeared self-absorbed when he was contemplating mankind’s future. “He was basically optimistic,” Gilot concluded, “even though he had encountered more than his share of opposition.” In painting portraits of her husband, what Gilot tried to capture was his spirit of discovery. “We were compatible mainly because, even though we were in different fields, we had that same intrinsic drive, the drive to get into an equation with the unknown. The spirit of discovery allows one to get something known out of the unknown. That’s what he had. That’s what I loved best in him.”

Though many could not fathom their marital arrangement, Salk and Gilot’s relationship matured as they grew to know each other better. “We found new discoveries all the time,” Gilot recalled. And Salk maintained, “I have achieved in terms of personal relationships as much with Françoise as I could possibly fantasize.”7 When asked in an interview how she had ended up with two of history’s most powerful men, Gilot replied: “Lions mate with lions.”1

Charlotte Decroes Jacobs is the Ben and A. Jess Shenson Professor of Medicine (Emerita) at Stanford University. She has served as Senior Associate Dean and as Director of the Clinical Cancer Center, and is the author of Henry Kaplan and the Story of Hodgkin’s Disease.

Adapted from Jonas Salk: A Life by Charlotte DeCroes Jacobs. Copyright © 2017 by Charlotte DeCroes Jacobs and published by Oxford University Press. All rights reserved.

References

1. Rose, C. “An Hour with French Painter Francoise Gilot” Charlie Rose, PBS (1998).

2. Gilot, F. Françoise Gilot: An Artist’s Journey – Un Voyage Pictoral Atlantic Monthly Press, New York, NY (1987).

3. Gilot, F. & Lake, C. Life with Picasso McGraw-Hill, New York NY (1964).

4. Jonas Salk Papers Mandeville Special Collections Library, University of California, San Diego (1969).

5. Harrisburg News, June 30, 1970.

6. “Jonas Salk Stalks Another Killer” Philadelphia Inquirer (1978).

7. Keyes, R. Jonas Salk unfolding. Human Behavior (1973).

Lead Image: Bettmann / Contributor / Getty Images