1

In the beginning it was known as TMM 41450-3. Then things got more personal.

Yes, life had already taken to the heavens, long ago in the Carboniferous, eons before TMM 41450-3’s discovery in the spring of 1971. Some claim it was from gills that wings had originally sprouted, others that they grew from limbs. Some believe wings were a novelty, arising in tiny nubs that bud during development. There is little to go by; the guessing game rules. But whether wings on the Insects came from breathing or walking, in the waters or on land; whether they had or did not have a prior history—they needed to lift but ounces. And this, in comparison to TMM 41450-3, was child’s play.

It was only later that the true challenge came, in the line of the Vertebrates. For there was lift and drag and thrust to navigate, and the terrible weight of the bones. Yes, after TMM 41450-3 evolution would yet converge, copying the ingenious solution. But before the birds, before the bats, before the planes, it was the lizards who took to the skies.

2

Much had transpired since the first fish walked onto land. For after a time, by laying eggs, the tetrapods could forsake the waters completely. It was then that they split into two separate lineages: the sauropsids that would lead to the dinosaurs, and the synapsids that would lead to man.

On the human side countless lineages rose and fell, their names exotic and now forgotten: Caseids, Ophiacodontids, Gorgonopsians, Venjukoviamorphs. But there was progression, too, along a signal mammal axis: nostrils that moved from the front to the back of the mouth, so that their bearers did not need to hold their breath while they chewed; legs that fit below the bodies rather than sprawling to the sides so that trotting replaced waddling, the up-and-down movement relieving the S-shaped slither, decoupling breathing from ambling. And there were the brains, principally, that swelled and grew longer in development, tearing out the loose rear bones of the jaw, fashioning the delicate middle ear, ballooning to create the neocortex. This, in the end, would make all the difference.

But how to pull upward, into the heavens? It was the lizards who solved the puzzle.

The other lineage began with small two-legged carnivores, but grew into the fiercest forms the planet had known yet. In the waters, swordfish-shaped ichthyosaurs cut through the oceans, together with the serpentine-necked plesiosaurs, some 80 feet long. On land the dinosaurs romped, curdling the blood of all the creatures around them. And 220 million years ago, lizard cousins of the dinosaurs began tilting their heads to the heavens. For soon the pterosaurs would take to the great big blue above.

3

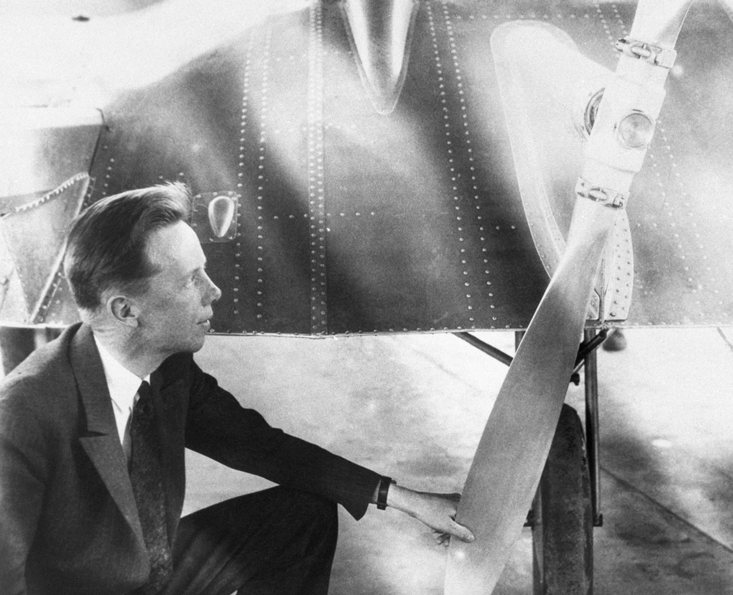

John K. “Jack” Northrop was born in Newark, New Jersey. At 21, in 1916, he became a draftsman for the Loughead Aircraft Manufacturing Company, founded four years earlier by the Loughead brothers, Allan and Malcolm. There was the “flying boat,” setting the American nonstop record for longest seaplane flight, from San Francisco to San Diego. There was the revolutionary monocoque fuselage of “the poor man’s airplane,” whose folding wings allowed it to be stored in a garage. The company folded in 1921, but the Loughead brothers opened shop again in 1926. Now there were Wiley Post and Amelia Earhart, flying Northrop’s Lockheed Vega monoplane into the record books. Northrop even lent his hand to the wing of T. Claude Ryan’s M-1, a bird that would set in motion Charles Lindbergh and the Spirit of St. Louis.

Chief engineer now of his own corporation, Northrop seemed an endless fountain of invention. There was the A-17 attack plane for the Army Air Corps, and for the Navy, the BT-1 bomber. There was the world’s first stressed-metal-skin commercial plane, the Alpha; the 200-miles-per-hour Beta; and, to revolutionize “airmail,” the Gamma. When the war came, it brought with it the P-61 Black Widow night fighter. With its radar-guided armaments it practically shut down Hitler’s night raids, planting fear in the enemy and saving scores.

Northrop was obsessed with his airplanes: He was born to revolutionize aviation.

For Northrop’s heart was in the skies.

4

But how to pull upward, into the heavens? It was the lizards who solved the puzzle, defying the dictator, Gravity.

First there were the bones to hollow, and their walls to strengthen with internal struts. Gradually, fortified, the walls could diminish until they were as thin as iron leaves. Then there were the hind limbs, which in an explosive spurt would launch their bearers upward: these would need to redouble and toughen. But most important of all was the lengthening of the ring finger, the fourth digit on the forelimb, once an equal among mates. For as it grew and extended, grotesquely elongating, a membrane of skin enveloped it and did not let go, forming a sail between itself, the shoulder, and the hind leg. Thus could the bones on each side become like a half-mast, supporting a wing surface, durable and taut. And as the wings became blade-like, growing aerodynamic, they thickened in the direction of travel and tapered behind. Spinning in vortices, air could travel more quickly now above the long narrow wing than below it, creating the pressure difference that would lift them into the skies.

Later, independently, birds and bats would copy the model, and, feeling clever, human aircraft designers would one day call it a cambered airfoil.

5

Early in the spring of 1971, a 22-year-old graduate student named Douglas Lawson made a big discovery. Atop a sandstone ridge in Big Bend National Park in Texas, he uncovered the world’s largest pterosaur yet.

Already in the 1800s they’d been unearthed from limestone, their names becoming legend: Dimorphodon, Nyctosaurus, Pterodactylus, Tapejara. Some had bulbous beaks, dodo-like; others, shovel-shaped ones crowded with teeth; still others, elegantly tapered ones as fine as sharpened quills. Some had giant crests, perhaps to woo their lovers, perhaps as heavenly rudders. There were those that snatched flying insects in midair; others, fish from the surface of the seas; still others, cockles in the estuaries and shallows. They were insectivores, carnivores, maybe even scavengers. But taking to the air, surprisingly, they would all escape terrestrial predators, develop new ways to hunt, and widen the range for mating. It was from above that the pterosaurs discerned the Earth, and all its living creatures. Alone in the other-world, for 150 million years they were masters of the skies.

When it flew, exploiting thermals, it could travel 10,000 miles in a single flight.

The known pterosaurs, more than 100 species strong, ranged from large to the size of sparrows, and yet not one was as colossal as this lizard-bird mammoth of the Cretaceous. Unbelieving, Lawson went digging, and soon found what he looked for: the thin, drawn-out plow-shaped skull, unearthly, with the eyes set like a toucan’s at the base of the crested head; the serpentine neck vertebrae, longer than could be imagined; the hollow bones and supporting struts; the fossilized fur, indicator of warm-bloodedness; the quadrupedal launch pads. And finally the fourth finger, elongated beyond comprehension, until it formed a strut that supported a massive wing, 50 feet across.

It was clear: On land, the giant creature stood upright on its forelegs with its wing membranes folded like umbrellas, as tall as a giraffe. When it flew, exploiting thermals, it could travel 10,000 miles in a single flight. More fantastic than any dragon, the tailless beast pushed the limits of biomechanics. It was the greatest flying machine ever invented.

His hand shaking, Lawson scribbled on the canister: TMM 41450-3.

6

Sure, there was the F-89 Scorpion all-weather interceptor, the first American nuclear-armed fighter. There was the X-4 Bantam research plane that Chuck Yeager used to investigate near-sonic flight. Later there would be the SM-62 SNARK, the country’s first guided intercontinental ballistic missile; the T-38 Talon; and the F-5 Tiger. But despite all these, there was only a single success that mattered. For there was always one dream in John K. Northrop’s soaring heart.

Tailless, no fuselage, high-lift, low-drag—early on, Northrop determined: He would build the world’s first “Flying Wing.” A plane without a tail? To most the thought was laughable. But Northrop knew that the heavens cried out for it. And he would not disappoint their gods.

It was during World War II, when the Earth was scorched and burning, that Northrop began to design the wings that would first take to the skies. One after the other they arrived, in succession: the first all-magnesium, all-welded aircraft, the XP-56 fighter, and after that, the XP-79, its pilot prone. Then came the four-engine-powered B-35, “poetry in motion.” Without the weighty fuselage, the tail surfaces, and the bulky engines and cowlings, rather than overpowering drag the flying wings reduced it. Soon they could deliver the same payload 25 percent farther, faster, higher.

A sliver in the sky, they’d be difficult to shoot down or detect by radar.

But Northrop’s greatest plane of all was yet to arrive; it would come when the din of bloodshed had subsided. Its climb rate and low noise and vibration levels let it glide almost silently, 40,000 feet above. With a range of 10,000 miles and a wingspan of 170 feet, it was a knife’s edge cutting up the sky at 464 miles per hour. Climb, bank, dive: its dual hydraulic systems made operation easy. For the B-49 bomber was the most awesome bird ever to climb into the sky.

Northrop’s vision, alas, would not in the end go into production. Mysteriously, the U.S. Air Force ordered the flying-wing bombers on the assembly line scrapped, the existing prototypes destroyed, the jigs and the dies abandoned. Instead, a more conventional airplane was duly contracted to the competition: the B-36, with a fuselage and a tail like all the rest of them. Northrop retired prematurely and never recovered. Despite all his triumphs, he went to his grave a broken man. For there was one dream to which he’d fastened his desires.

7

In the end there would be a double comeuppance, or at least a bittersweet ode to solitude. For in his old age, Northrop received a letter from NASA: the flying wing had been rediscovered. Following his death, the B-2 Spirit stealth bomber would be constructed, the fiercest aircraft the world had yet known.

A year before that letter came, an even greater gesture was occasioned when, according to the dictates of Linnaeus, TMM 41450-3 was given its proper Latin name. Lawson christened it Quetzalcoatlus, after the feathered serpent god of the Aztecs, born to a virgin who had swallowed an emerald, or so according to legend. Representing wind and learning, Quetzalcoatl was the boundary maker and transgressor of earth and sky, a creator of mankind. But bowing to history, and the intricacies of human sentiment, Lawson gave it a second name—Quetzalcoatlus northropi—for the pioneer who had learned its secrets.

And yet, like the B-49, Quetzalcoatlus would be mysteriously discarded. It and Northrop had arrived before they were summoned; this was their tragic common fate. Prematurity would be both creatures’ undoing: no lonelier destiny has been known to date.

The pterosaurs would go extinct, eclipsed by the birds, the only surviving dinosaurs. After the pterosaurs, reptiles would need to settle for being alligators in muddied waters, hopelessly sluggish turtles, and snakes slithering on their bellies in the dirt. And while the birds would flourish, and after them the bats, never again would nature match the flying lizard’s lonesome majesty.

This, perhaps, was by some cosmic design inevitable. For when all was said and done, there was nothing personal about it, in the least.

Oren Harman is a professor of the history of science at Bar Ilan University. His book The Price of Altruism won the Los Angeles Times Book Prize in Science and Technology and was a New York Times Notable Book of the Year.

From Evolutions by Oren Harman, to be published by Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

Lead Image credits: Science Photo Library / Getty Images; Ivan Cholakov / Shutterstock