Here is the predicament that most of us seem to be in. We are not virtuous people. We simply do not have characters that are good enough to qualify as honest, compassionate, wise, courageous, and the like. We are not vicious people either—dishonest, callous, foolish, cowardly, and so forth. Rather we have a mixed character with some good sides and some bad sides. This is the most plausible interpretation of what psychology tells us. It is also true to our lived experience in the world.

Those are the facts as I see them. Now comes the value judgment—this is a real shame. It is very unfortunate that our characters are this way. It is a good thing—indeed, a very good thing—to be a good person. Excellence of character, or being virtuous, is what we should all strive for.

Admittedly, the news is not all bad. It would be a lot worse if most of us were vicious people. Imagine what it would be like to live in a world full of mostly cruel, self-centered, dishonest, and hateful people. It would be hell on earth.

Nevertheless, at this point we are confronted with a significant gap:

What strategies are there to try to develop a better character, and which of these strategies show substantial promise? In my book The Character Gap: How Good Are We?, I consider a number of different strategies. One I find quite interesting is what we might call “virtue labeling.”

Suppose you come to believe, as I do, that most of the people we know do not have any of the virtues. So your friend, your boss, your neighbor … you need to change your opinion of all of them.

Now here is the interesting idea—even with this new outlook firmly in mind, you should still go ahead and call them honest people next time you see them. You should still praise them for being compassionate. You should go out of your way to comment on their courage.

Why would you do such a thing? Isn’t that just wrong?

Let’s wait and see. The idea is to attach a label to people you know. Labels make a big difference. For with that label attached to them, there is a good chance that they will try to live up to it. And perhaps the more they care about living up to the label, such as honest person, the more they will actually become that honest person.

Extoll the honesty of your friends, even if you have to bite your tongue in doing so.

Thanks to some clever experiments, we know that this kind of thing works quite well, at least in some contexts. Here are examples:

The tidy study: The most famous experiment was published back in 1975 by the University of Nebraska psychologist Richard Miller and his colleagues. One group of fifth graders was labeled “tidy.” The researchers tried to persuade a second group of kids to be tidier. A third group functioned as the controls. The results? It was the “tidy” group that actually was the tidiest.1

The tower-building study: Another study with children, this time conducted by Roger Jensen and Shirley Moore in the 1970s at the University of Minnesota, had one group receive “cooperative” labels, while a second received “competitive” labels. Later in the same day, the kids played a tower-building game. It turned out that by the time they played the game, many of the children forgot their labels, but still the ones in the “cooperative” group placed double the number of blocks in the game!2

The environmental study: To take a more recent study from 2007, consider what happened when the economist Gert Cornelissen at the Pompeu Fabra University in Italy used the label “very concerned with the environment and ecologically conscious” for some customers looking for TVs. These labeled customers turned out to be more environmentally responsible in their shopping than (i) shoppers in a control group, and even (ii) shoppers who had been urged to be more environmentally mindful in their spending.3

What is going on here? What explains these results?

One thing we know is that the label does not need to work its magic at the conscious level; indeed, many participants did not even recall the earlier labeling. Yet it still made a difference. Furthermore, we know that when we get labeled a certain way, other people will expect us to act that way in the future. If the label is a positive one, we don’t want to let them down. We like being thought highly of and want that to continue.2,3 Beyond these preliminary observations, though, there does not seem to be a well-developed and widely accepted model in the psychology literature to explain how character labeling makes such a difference. For instance, do people actually come to believe that they are honest, and integrate that belief into how they think and act? Or is it just that they know that others believe this about them, regardless of whether they share this perspective, too?

Leaving aside this unfortunate lack of clarity, you might have noticed that the studies above did not involve clear examples of moral traits—the examples were tidiness, competitiveness, and ecological consciousness. So do we have any reason to think that this labeling effect happens in the moral realm too? Yes we do. For the same pattern of results shows up in studies involving what are obviously morally relevant labels. In an early study, for instance, Robert Kraut at Carnegie Mellon had his assistants knock on doors during the day and ask people at home to make a donation to a heart association. For those who did donate, half were labeled, “You are a generous person. I wish more of the people I met were as charitable as you,” and half were not labeled.4 For non-donors, half were labeled as being “uncharitable” and half were not.

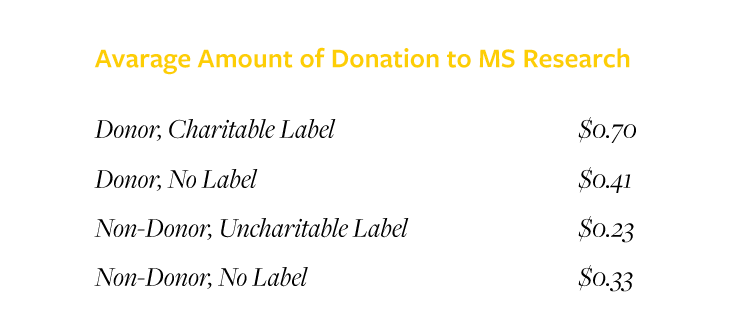

What difference did these labels make? Well, a week later the same people were this time asked to donate to a local funding-raising campaign for multiple sclerosis. Here were the results:4

Note the significant difference in donation amount in the first two lines, a difference that seems to be influenced by the difference in label.

Or consider how Angelo Strenta at Dartmouth College and William DeJong at Boston University gave the label “kind, thoughtful person” to some participants, and a few minutes later an actor dropped a stack of 500 computer punch cards. These labeled folks helped to pick up an average of 163.5 cards and spent 30.1 seconds doing so. By comparison, the results were 84.4 cards and 21.6 seconds for those in the control group who never got the label!5

So indeed labeling people with moral virtue terms does seem to make a difference, at least as far as the preliminary evidence suggests. Given this, let’s think for a moment about how we might take these findings and use them in developing a strategy for bridging the character gap. One idea goes something like this. Start praising your children or your spouse for their compassion, even if you have reason to doubt it. Extoll the honesty of your friends, even if you have to bite your tongue in doing so. Whenever anyone does something nice to you, thank him or her for being a gracious or loving or kind person, rather than just showing appreciation for a particular kind act.

The more word gets out, the less effective the labeling will become as people grow suspicious.

Suppose you are a middle-school teacher. You have reason to suspect that some of your students might have cheated on a recent homework assignment. Soon you have to give them an important test, and the classroom is crowded. You worry that there might be some temptation to glance at other exams or trade answers under the desks. You could ask them to not cheat. You could remind them of the possibility of suspension or expulsion. Yet what comes to mind is the psychology research on the power of labeling. So instead you go out of your way to convey the message in the days leading up to the test that you think they are honest people. Then on the big day you say something like, “Given that this is such a trustworthy class, I’m not worried about copying and I’m not going to separate you.” Or perhaps you try, “Because I know that you all care about honesty, I’m sure that you’ll do the right thing.”

The hope, in all these examples mentioned above, is that you will see a change over time as these folks—your family members, friends, and students—actually improve their behavior, even if gradually, in the direction of living up to the expectations of the label.

That is the hope, at least. But how realistic of a hope is it, really? It is certainly a clever idea. But I think we should be hesitant to adopt it, for three important reasons. First, we really have no idea if virtue labeling actually works.

Wait, didn’t I just mention a bunch of studies where it does? But we need to be careful. For one thing, there have actually not been that many studies done to study this phenomenon, especially when it comes to using virtue labels, which is our main interest here. Of course, that doesn’t by itself show that the strategy is unpromising. It could still end up working really well. It just means that we need to do a lot of work in testing it out first.

We also do not know whether a virtue label encourages more virtuous behavior only in the short run,5 or whether the effect persists.4,6 For that kind of discovery, we would need longitudinal studies which follow the same people over time and regularly assess the impact of these labels on their behavior, say over the course of months or even years.

In addition—and this is the third reason for hesitation—even if someone’s behavior does gradually improve over the long run due to the labeling effect, we know that this alone would not automatically make someone a virtuous person. Motivation matters to virtue too. So do people labeled as compassionate or honest come to cultivate the right kinds of motives over time?

You might think not. As noted above, people who receive the virtue label seem to behave better. Is that because, for instance, they genuinely care about others (compassionate motivation) or they genuinely care about telling the truth (honest motivation)? Or is it because they want to live up to the label they have been given? If it is the latter, then that is hardly a virtuous kind of motive. It is self-interested, with the focus on making a good impression or not disappointing someone, which is not where it needs to be for virtue.

Do you really want to adopt a strategy—for promoting virtue, after all—that has to rely on multiple layers of deception to be successful?

So I can’t get very excited about this strategy just yet, given our limited understanding of it. But suppose that in the next hundred years, the stars align. Lots more research is done on the effects of virtue labeling, it probes motivation as well as action, and the results are surprisingly positive in showing long-term virtuous effects. Even still, there is a reason to be nervous.

How can that be? Yes, I admit that people becoming more virtuous would be great. But what about the means of getting there? Isn’t there something downright disturbing about labeling people with virtue terms when you know that they don’t have any of those virtues?

Now for some people the outcome is all that matters. The ends justify the means. Since this strategy would—if the stars aligned in the way I just described—give us a great outcome, then it is perfectly fine.

However, many of us are not prepared to go that far in general and say that the ends always justify the means. I am one of those people. To my mind, this way of thinking could be used to try to excuse terrible atrocities along the way to achieving something worthwhile.

When it comes to virtue labeling, we are not talking about terrible atrocities of course. Yet there still might be something morally questionable about praising someone for being an honest person, while all along believing she is not in fact honest. My goal is supposed to be the noble one of contributing to her becoming a better person in the long run. To achieve that goal, though, I am supposed to get her to believe something about herself that I know is not true, and do this in a way that sounds genuine and heartfelt. In other words, I am to come across as sincere in thinking she is honest, thereby enabling her to trust me and believe it herself. A clever ruse on my part that can sound morally repugnant—hypocritical, deceptive, manipulative, and a violation of someone’s autonomy. To many people, it is all of these things.

Indeed, if you were really committed to this strategy for bridging the character gap, you would not want to tell people about it. You would even be annoyed at someone like me spilling the beans. For the more word gets out, the less effective the labeling will become as people grow suspicious about whether the praise of their characters is genuine or manipulative. So there is another level of deception involved here—in order to effectively implement this strategy you would need to take steps to suppress other people knowing about the strategy!

None of this sounds very good, does it? Do you really want to adopt a strategy—for promoting virtue, after all—that has to rely on multiple layers of deception to be successful?

By now you might be fed up with this strategy. But I think we should be fair to both sides. I always tell my students that this is one of the things they need to do to become good philosophers. So here is one parting thought in defense of virtue labeling.

Consider placebos. Doctors have been using them on patients for decades, and there is some evidence that they are effective. They are not legally banned, nor are they morally condemned by the American medical profession for use in clinical trials (although there is more resistance to using placebos in clinical practice).7

Now think for a moment about what placebos involve. A doctor gives a sugar pill to participants in a trial, knowing that it is fake. In the process the doctor does her best to come across as medically authoritative and confident, so that the participants believe they are getting an effective drug treatment. Otherwise the placebo won’t work. So she must, in other words, intentionally deceive the patients for their own good in the long run. Nor does she want word about placebos to get out to the general public, as otherwise participants in the trial might start becoming suspicious, which would undercut the effectiveness of the placebo in the first place.

The parallels to virtue labels should be obvious. Indeed, these labels can be viewed as a kind of placebo. Where does this leave us, then? We might try to think of important differences between the virtue labeling case and the doctor case. If there are none, then if you are okay with placebos, you should be okay with virtue labeling. Or if you are not okay with virtue labeling, then you should not be okay with placebos. Where do you end up?

I personally still think the deception involved with using this virtue labeling strategy is a major problem. But I know that others might assess things differently, and I am open to being wrong.

Christian B. Miller is the A.C. Reid Professor of Philosophy at Wake Forest University. His writings have appeared in the Wall Street Journal, Dallas Morning News, Aeon, Christianity Today, and Slate, and he is the author or editor of eight books. This excerpt is from his most recent book, The Character Gap: How Good Are We?, and is reprinted with permission from Oxford University Press.

References

1. Miller, R., Brickman, P., & Bolen, D. Attribution versus persuasion as a means for modifying behavior. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 31, 430-441 (1975).

2. Jensen, R. & Moore, S. The effect of attribute statements on cooperativeness and competitiveness in school-age boys. Child Development 48, 305-307 (1977).

3. Cornelissen, G., Dewitte, S., Warlop, L., & Yzerbyt, V. Whatever people say I am, that’s what I am: Social labeling as a social marketing tool. International Journal of Research in Marketing 24, 278-288 (2007).

4. Kraut, R. Effects of social labeling on giving to charity. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology 9, 551-562 (1973).

5. Strenta, A. & DeJong, W. The effect of a prosocial label on helping behavior. Social Psychology Quarterly 44, 142-147 (1981).

6. Grusec, J. & Redler, E. Attribution, reinforcement, and altruism: A developmental analysis. Developmental Psychology 16, 525-534 (1980).

7. See American Medical Association Opinion 8.083—Placebo use in clinical practice. American Medical Association Code of Medical Ethics (2006).

Lead image: Renny / Andrey_Kuzmin / Shutterstock; Pixabay