The morgue was inside Brooks Brothers. I was standing at the corner of Church and Dey, right next to the rubble of the World Trade Center, when a policeman shouted that doctors were needed at the menswear emporium inside the building at One Liberty Plaza. Bodies were piling up there, he said, and another makeshift morgue on the other side of the rubble had just closed. I volunteered and set off down the debris-strewn street.

It was the day after the attack. The smoke and stench of burning plastic were even stronger than on Tuesday. The street was muddy, and because I was stupidly wearing clogs, the mud soaked my socks.

I arrived at the building. In the lobby, exhausted firefighters and their German shepherds were sitting on the floor amid broken glass. A soldier stood at the entrance to the store, where a crowd of policemen hovered. “No one is allowed in the morgue except doctors,” he shouted.

I entered reluctantly through a dark curtain. Cadavers had always made me feel queasy, ever since those dog days in the anatomy lab in St. Louis. In the near corner was a small group of doctors and nurses, and next to them was an empty plastic stretcher. Behind the group was a wooden table where a nurse and two medical students were sitting grim-faced, looking like some sort of macabre tribunal. Brooks Brothers shirts were neatly folded in cubbyholes in the wall. They were covered in grime, but you could still make out the reds and oranges and yellows. In the far corner, next to what looked like a blown-out door, was a pile of orange body bags, about 20 of them. Soldiers were standing guard. In the store’s dressing room were stacks of unused body bags.

The group was discussing the protocol for how to handle the bodies. A young female doctor said that she didn’t think anyone should sign any forms, lest someone think that we had certified the contents of the bags, which we were not qualified to do. That, she said, was up to the medical examiner. Someone asked whether a separate body bag was needed for each body part, but no one knew the answer. The leader of the group was a man in his 50s. I looked at his badge. It read “PGY-3.” He was a third-year resident, which meant that I was probably the most experienced doctor in the room, a thought that deeply disturbed me. I had been a cardiology fellow for only a couple of months.

At this point, some National Guardsmen brought in a body bag and laid it on the stretcher. The female doctor unzipped it and inspected the contents. “Holy Mother of God,” she said, and she turned away. In the bag was a left leg and part of a pelvis, to which a penis was still attached. The leg itself hardly seemed injured, but the pelvic stump was beefy red and broken intestines were hanging out of it. A pants pocket was partially covering the pelvis and was emptied of change; this pocket was put in a separate bag. A policeman said that part of the victim’s body had been brought in earlier, along with a cell phone.

That was actually good news. If the victim had the numbers of family members on his speed dial, he would be quickly identified. But identification wasn’t my job. Processing was.

After five minutes, the bag was zipped up. The older male doctor, who had been working there for hours, said he had to leave. The other doctor also said she had to get away for about an hour. “Are you a physician?” she asked me. “Yes,” I replied. “Great,” she said. “You can take over.” Then she started giving me instructions on how to catalog the body parts. Basically, I had to call out the contents of each bag to a nurse, who would write them down on a form. That was it.

The ground was strewn with paper and abandoned shoes, as if people had literally vanished in their tracks.

I was in a fog. Suddenly I was in charge, but I wasn’t a pathologist. I was just improvising. I recalled my friends who had done medical clerkships in Africa. They had told me of the terrible tragedies and deep frustration of not having proper medical supplies. But we were not suffering from a lack of supplies. This was not third-world medicine. It was netherworld medicine, without rules.

Another body bag came in. This one had a spleen, some intestines, part of a liver. After sifting through the bag’s contents, I began to feel ill. I walked past headless mannequins and out into the smoke-filled air.

Our triage center had been set up in a firehouse within yards of the World Trade Center plaza. From here, the destruction was even more profound. Bombed-out cars, coated with an inch of cement dust, lined the muddy streets. Steel beams of the demolished towers stood up in the rubble like butts in an ashtray. Giant hoses and wires coiled from the buildings. Everywhere there were shattered windows and broken glass. The ground was strewn with paper and abandoned shoes, as if people had literally vanished in their tracks. Dr. Abramson, the Israeli echo chief who had accompanied me downtown, gazed at the carnage. “I thought I had seen everything,” he said softly.

Our center was equipped with supplies—oxygen tanks, crates of foodstuffs—that had been ferried down by ambulance. A fire ladder served as a scaffold for bags of fluid. Twenty or so doctors and nurses staffed the different “departments”: trauma, burns and injuries, wounds and fractures. I was in asthma and chest pain. We treated firefighters suffering from smoke inhalation, giving them oxygen to breathe and albuterol mist to help open their airways. But otherwise things were eerily quiet.

On my way downtown the previous afternoon with a caravan of doctors from Bellevue, I had braced myself to confront throngs of seriously injured people. But there was no one around except rescue workers. “Where are all the patients?” I blurted out when I arrived, thinking they might be at a different location.

“They’re all dead,” a colleague replied.

Now we sat in the haze, ash still falling like snow, trading stories. A physician told me he happened to be standing outside the first tower when it collapsed. “I ran under a bridge,” he said. “There was huge debris falling all around me. Every step I took, I kept saying to myself, ‘I can’t believe I’m not dead yet; I can’t believe I’m not dead yet.’” Then he began hearing strange thuds. Those, a firefighter told him, were people jumping off buildings.

We sat for hours, waiting for something to happen. Then, in the early afternoon, word came that a victim, a young woman, had been found alive in the rubble. An American flag was hoisted at the site, and rescue workers began the painstaking work of extricating her. By late afternoon, about 50 doctors and other volunteers had formed a human chain from the street to the top of the rubble, several stories high, and were passing down the debris, piece by piece. Two large cranes with huge jaws then took the shrapnel and transferred it to waiting trucks.

I stayed until evening, hoping to help in some way, but I’d spent the better part of two days at the site, away from my worried wife, and I was exhausted. They were still working when I left.

For weeks after I returned to work that fall, the smell of dead bodies wafted from the morgue tents set up at First and Twenty-Ninth, outside Bellevue. I had been cutting through the street to get to conferences at the main hospital, but no more. Then, one day, I heard that the victim who’d been saved at Ground Zero was on the cardiac arrhythmia service, and not because of her broken leg. After her rescue, recurrent ventricular arrhythmias inexplicably set in, causing her to keep passing out. Medications couldn’t suppress the arrhythmias, psychological counseling hadn’t helped, and surgical options, including an implantable defibrillator, were being considered. By the late fall, she was on the catheterization table as electrophysiologists at Bellevue tried to figure out what had gone wrong inside her heart.

Heart rhythms are strongly influenced by emotional states. But how do emotions trigger rhythm disturbances? How does psychological injury disrupt the heart of a traumatized young woman that has beaten a billion times without fail? Bernard Lown, co-recipient of the Nobel Peace Prize for his work with International Physicians for the Prevention of Nuclear War, performed some of the seminal studies exploring such questions. As a high school student, Lown was fascinated by psychiatry, but in medical school he quickly became disenchanted by the subjective nature of the discipline. However, his fundamental interest in mind-body interactions persisted throughout his career. As a cardiologist in the 1960s, he decided to investigate whether psychological stress could trigger sudden cardiac death. In his earliest experiments, he studied ventricular fibrillation in anesthetized mice. To predispose the animals to fibrillation, Lown experimentally blocked a coronary artery, causing a small heart attack. He found that 6 percent of his animals developed ventricular fibrillation because of the coronary occlusion. However, Lown discovered that fibrillation occurred 10 times more frequently when regions in the brain that mediate anxiety were electrically stimulated at the same time the coronary artery was occluded. Lown and his colleagues later found that they did not have to stimulate the brain to produce a fatal arrhythmia. Stimulating autonomic nerves that mediate blood pressure and heartbeat largely did the same thing.

But what Lown really wanted to show was that psychological stress by itself could trigger dangerous arrhythmias. He decided to study premature ventricular contractions (PVCs) in dogs. These extra heartbeats are often a precursor of fatal arrhythmias because they can strike during the vulnerable period of the cardiac cycle. PVCs indicate that the heart is in an excited and, therefore, vulnerable state. For the psychological stress, Lown put each dog in two different environments: a cage, in which the animals were essentially left undisturbed; and a sling, in which they were suspended, paws just off the ground, and received a single small electrical shock on three consecutive days. When the dogs were later returned to these two environments, Lown observed a remarkable difference. Animals placed in the cage appeared normal and relaxed. However, when they were transferred to the sling, they became restless, and their heartbeat and blood pressure went up. The rate of PVCs rose dramatically, too. Even months later, the memory of the minor sling trauma was deeply embedded in the dogs’ brains and profoundly affected cardiac reactivity. These findings, Lown writes in his book The Lost Art of Healing, demonstrated that psychological stress, already known to be a risk factor for coronary artery disease, can substantially increase susceptibility to malignant arrhythmias, too.

Predictability, control, and feedback about the effectiveness of coping all reduce shock-induced stress.

Later, working with psychiatrists at the Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston, Lown’s team found that survivors of sudden arrhythmias often experience acute psychological stress preceding their cardiac arrest. Nearly 1 in 5 of a group of 117 patients suffered public humiliation, marital separation, bereavement, or business failure in the 24 hours prior to their attacks. Moreover, Lown and his colleagues showed that medications that block sympathetic nervous system activity, such as beta-blockers, protected patients from those arrhythmias. Meditation largely did the same thing.

Lown’s research confirmed for the first time that emotional stress can initiate life-threatening arrhythmias. This conclusion is now widely accepted in medicine. We all agreed, for example, that post-traumatic stress was exacerbating the arrhythmias in the young woman rescued at Ground Zero. But in the months after 9/11, I learned a remarkable corollary to Lown’s observations: Not only are arrhythmias triggered by psychological trauma but they (or at least their treatment) can cause it as well. Such stress can then feed back onto the heart, creating a malignantly vicious cycle. The mind-heart link, in other words, goes both ways. One night in November, two months after the attacks, I got to see this up close.

I met Lorraine Flood on a rainy evening in the faculty dining room at NYU Medical Center, where about 20 patients with implantable cardiac defibrillators had assembled for a support-group meeting. In June 1998, eight years after her first heart attack on the eve of her son’s wedding, Flood underwent an hour-long operation to implant a pager-sized defibrillator under the skin of her left chest. Like most patients, she was told that the device would monitor her heartbeat and apply a shock if the rhythm degenerated into something dangerous. “I was so relieved,” Flood told me that night. “I used to worry, ‘If something happens, I may not survive it.’” But then her defibrillator started working.

Flood was sitting with her husband, Al, with whom she had driven out from Colonia, New Jersey, where he was a bank executive and she owned a travel agency. She was a tall 71-year-old woman with a regal bearing and salon-done blondish hair. I asked her why she had come to the meeting. “I’ve had a horrible time,” she replied. “I still wake up every morning and pray to God and say, ‘Lord, please, no shocks today. Please, no shocks today.’”

They started a few weeks after her implant, when she began to have arrhythmias that caused her defibrillator to fire. “I used to see this bluish-white light, and that was my warning I was going to get shocked,” she said. She would quickly sit down and then feel the device discharge into her chest. “Nobody told me what it would be like. Oh, they said you’d feel a little something, but they never told me it was like a donkey rearing his hind legs and just with all the power he has hitting you right in the chest with full force—bang!”

Once, she was shocked 16 times in nine days. “I was sitting on the couch when I started to get the shocks. I screamed like a banshee. My poor housekeeper didn’t know what to do. She ran upstairs and got me a bathrobe and slippers to go to the hospital. I said, ‘Catherine, I can wear clothes!’”

On the phone with her doctor, she was jolted by another intense shock. “I have always had a high threshold for pain—I never take Novocain at the dentist’s—but I just couldn’t handle it.”

One afternoon, she was at her grandson’s preschool when she saw the bluish-white light. “I felt it was warning me that I better get out of the room so I don’t frighten the children,” she recalled. She went into a bathroom, where she got what she described as a “mild shock.” Later, when her doctors checked, they said the defibrillator hadn’t fired. “They said it was a phantom shock,” Flood said. “But no one can tell me it wasn’t related to the defibrillator. I’ve been shocked enough times to know what it was.” Flood’s defibrillator was adjusted to make it less sensitive to arrhythmias, but she continued to feel nervous, increasing the likelihood of future shocks.

She stopped going to work and hired a full-time driver. She stopped going out with friends or singing in the church choir and eventually resigned from the school board. She had tickets to The Lion King on Broadway but didn’t use them because she was afraid of getting shocked during the performance. “Dr. Shapiro said to me, ‘So what if you scream in the middle of the play? You’ll scream, and then you’ll watch the rest of the play.’ But I couldn’t do it.”

Flood soon developed a Pavlovian fear of places where she had been shocked. One was her shower stall. “It once threw me against the wall of the shower,” she said. “Well, you never saw anyone leave that shower so fast. I had shampoo in my hair, suds all over my body, and I ran into my bedroom screaming, and Al came running in. It was terrible.” She started using her husband’s bathtub. “I couldn’t even look at the shower; that’s how frightened I was,” she said. “Then I decided, ‘Lorraine, this is ridiculous.’ One day I opened the shower door and put the water on. But I couldn’t go in. I just watched the water.”

I walked over to the buffet table, where Dr. Shapiro, who had invited me to the meeting, was chewing on a chicken skewer. He had just gotten out of a procedure and was still wearing blue scrubs.

The meeting, Shapiro explained, was intended for people to open up about their defibrillators. Since the 9/11 attacks, he said, patients were reporting more defibrillator shocks than ever, probably because of increased psychological stress. The rate of ventricular arrhythmias in patients with implantable defibrillators had more than doubled. One patient of his, he said, was so disturbed after getting repeatedly shocked that she held a séance at her home to rid it of “evil spirits.” Another had actually made Shapiro turn off his defibrillator. “He said he’d rather allow his life to end than deal with the pain and frequency of those shocks.” Shapiro mentioned the young woman who was rescued at Ground Zero. No treatment for her arrhythmias had worked. The next step was probably a complex radio-frequency ablative procedure in her right ventricle.

Psychologists have come up with two theories to explain the post-traumatic stress disorder after implantable defibrillator shocks. The first, classical conditioning, refers to the psychological pairing of a previously neutral stimulus (such as taking a shower) with a noxious one (painful shock) so that they elicit the same fearful response. As in Flood’s case, as well as for other patients at the support-group meeting—and, presumably, the young woman who survived at Ground Zero—fear can heighten arousal and result in even more arrhythmias and shocks. The fear subserves itself.

The second theory derives from experiments in which dogs were repeatedly subjected to electrical shocks. Compared with controls, animals that are powerless to regulate their shocks become physically exhausted and quickly cease to struggle, despite being given opportunities to avoid the shocks. Researchers have concluded that animals acquire a state of “learned helplessness.” Humans who experience frequent shocks develop a similar response.

What are you willing to give up to live a little longer?

The key to avoiding such a hopeless state is to take away the element of surprise. Rats repeatedly shocked without warning develop stomach ulcers, a sign of intense arousal. However, rats that can predict when they will be shocked because of a warning buzzer develop significantly fewer ulcers. Moreover, rats that can prevent some shocks by pressing a lever develop fewer ulcers than those that receive the same number of shocks but have no control over them. Ulcers are further reduced when the rats, after pressing the lever, are given a signal that the shock has been successfully prevented. In other words, predictability, control, and feedback about the effectiveness of coping all reduce shock-induced stress.

Piggybacking on such research, researchers at Wake Forest University investigated how to mitigate the startle response of humans to sudden defibrillator shocks. They delivered 150-volt shocks to the arms of 20 volunteers and asked them to rate the pain. Some shocks were delivered alone; others following a tiny, painless “pre-pulse” so subjects were prepared. The pre-pulsed shocks were rated less painful than the ones applied without warning. The analgesic effect was greatest in the subjects who felt the most pain to begin with.

However, nothing has proved more effective for anxious patients than simply reducing the number of shocks they receive. Reprogramming a defibrillator to make it less sensitive to arrhythmias is the mainstay of treatment. Most patients are also put on an anti-arrhythmic drug, like amiodarone, which can have serious side effects like lung and thyroid problems but which most cardiologists find acceptable if it prevents the occasional errant shock and subsequent psychological cascade. Patients also often work with a clinical psychologist who specializes in shock-induced anxiety and provides cognitive-behavioral therapy. Many (like Flood) require antianxiety medications or antidepressants. For some, the best treatment is simply refraining from the activities that induce the shocks in the first place—for example, the patient who kept getting shocked during vigorous sex. (His partner claimed to feel it, too.)

But despite efforts to make them more user-friendly, defibrillators, like any medical technology, are always going to involve a compromise: What are you willing to give up to live a little longer?

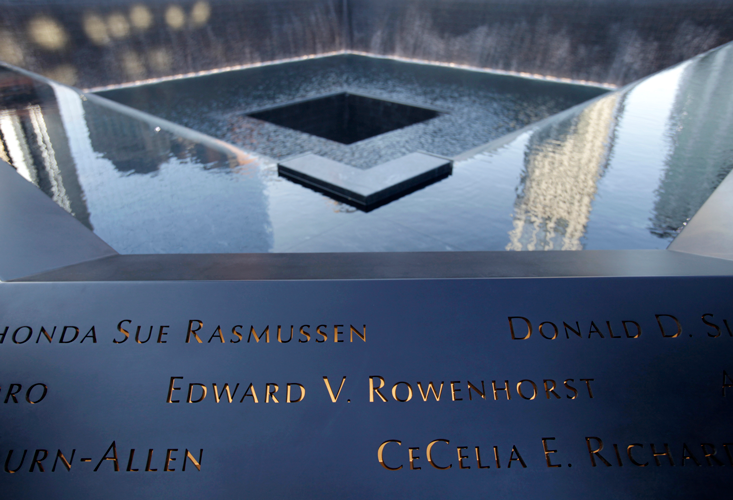

A couple of years ago, I finally took my children to see the 9/11 Memorial in downtown Manhattan. For more than a decade, I’d avoided reading almost anything about the 9/11 attacks, so I had no idea what to expect. Approaching the main square, near where I had cataloged body parts at Brooks Brothers, I started to feel queasy. My armpits became moist, and my heart started to race. A crowd was packed at the viewing wall, surrounding the granite reflecting pool where the South Tower had once stood. I thought once again of the young woman with arrhythmias who was rescued the day after the attack. I never did find out what happened to her. Maybe her arrhythmias eventually responded to medications (or meditation). Maybe she underwent the radio-frequency procedure that Shapiro had mentioned, or even surgery to cut the sympathetic nerves that mediate the heart’s response to emotional stress. More likely, she was implanted with a defibrillator to protect her from her heart’s meandering vortices. Whatever the case, I wondered whether she was still alive to see the monument. We pushed our way through a gap in the mass of people. I pulled my children up to the stone wall. And then I saw it: the black stone, the bottomless pit, into which water swirled. It looked like a reentrant spiral wave, the signature of a heart’s death. I closed my eyes. My head was spinning.

Sandeep Jauhar is director of the Heart Failure Program at Long Island Jewish Medical Center. He is the New York Times bestselling author of two medical memoirs and a contributing opinion writer for the New York Times.

Excerpted from Heart: A History by Sandeep Jauhar, published by Farrar, Straus and Giroux. Copyright © 2018 by Sandeep Jauhar. All rights reserved.

Users are warned that the work appearing herein is protected under copyright laws and reproduction of the text, in any form for distribution is strictly prohibited. The right to reproduce or transfer the work via any medium must be secured with the copyright owner.