In the annals of transportation history persists a tale of how automobiles in the early 20th century helped cities conquer their waste problems. It’s a tidy story, so to speak, about dirty horses and clean cars and technological innovation. As typically told, it’s a lesson we can learn from today, now that cars are their own environmental disaster, and one that technology can no doubt solve. The story makes perfect sense to modern ears and noses: After all, Americans love their cars! And who’d want to walk through ankle-deep horse manure to buy a newspaper? There’s just one problem with the story. It’s wrong.

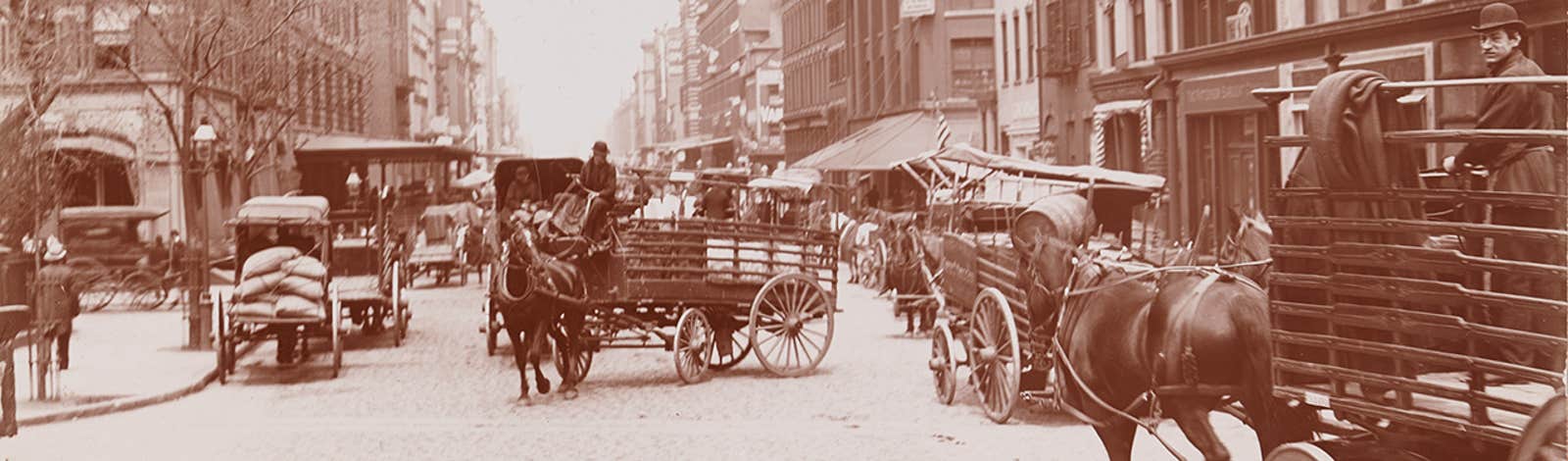

For a recent telling, you can turn to SuperFreakonomics, the best-selling 2009 book by economist Steven D. Levitt and journalist Stephen J. Dubner. The authors describe how, in the late 19th century, the streets of fast-industrializing cities were congested with horses, each pulling a cart or a coach, one after the other, in some places three abreast. There were something like 200,000 horses in New York City alone, depositing manure at a rate of roughly 35 pounds per day, per horse. It piled high in vacant lots and “lined city streets like banks of snow.” The elegant brownstone stoops so beloved of contemporary city-dwellers allowed homeowners to “rise above a sea of manure.” In Rochester, N. Y., health officials calculated that the city’s annual horse waste would, if collected on a single acre, make a 175-foot-tall tower.

“The world had seemingly reached the point where its largest cities could not survive without the horse but couldn’t survive with it, either,” write Levitt and Dubner. A main solution, as they portray it, came in the form of cars, which, compared to horses, were a godsend, their adoption inevitable. “The automobile, cheaper to own and operate than a horse-drawn vehicle was proclaimed an ‘environmental savior.’ Cities around the world were able to take a deep breath—without holding their noses at last—and resume their march of progress.” To Levitt and Dubner, this historical turnabout teaches that technological innovation solves problems, and if it creates new problems, innovation will solve those, too.

It’s far too simplistic an interpretation. Cars didn’t replace horses, at least not in the way we usually think, and it was social as much as technological progress that solved the era’s pollution problems. As we confront our current car troubles—particulate and greenhouse gas pollutions, accidents and deaths, wasteful swaths of the landscape dedicated to automobiles—these are lessons we’d do well to recall.

History loves smooth transitions, such as horses to cars. “There’s an assumption that you have this clean break between eras,” says urban historian Martin Melosi. “In the real world, that doesn’t happen.” The idea of a neat transition from horses to the automobile age is a history-as-approved-by-victors myth that elides several decades when horse travel declined but automobiles were uncommon, used primarily to haul freight. The automobile as we now conceive it, a personal transport machine, wouldn’t come along for nearly half a century.

The late 19th and early 20th centuries was actually the age of streetcars. Running on steel rails, a few pulled by horses but most powered by electricity, they were the dominant urban mode of vehicular transport. The first suburbs date to this time, rising along streetcar lines in Boston, Los Angeles, Pittsburgh, and other cities. The “streetcar suburbs” featured single-family houses branching off store-lined main streets, the very model of walkable, humane villages now celebrated by urban planners and citizens. Only a handful of wealthy drivers actually thought of cars as personal transportation, and that mostly involved weekend countryside jaunts.

To the average city dweller, the idea of a city oriented around transportation in cars, and especially privately owned cars carrying one or a few people, would have been incomprehensible. Indeed, the modern idea of a street as an artery, existing primarily to convey vehicles, would have been foreign, says Christopher W. Wells, author of Car Country: An Environmental History. Streets were more like parks, used by streetcars, horses, cars, and pedestrians, but also as playgrounds and gathering places.

In this environment, motor vehicles were seen as dangerous intruders, a threat to public safety and especially the safety of children. Blame for accidents was laid entirely on drivers. In 1923, Cincinnati residents even required that cars operating in the city be modified so they couldn’t go faster than 25 miles per hour. “Today we learn that streets are for cars. That’s 100 percent opposed to the dominant view a century ago,” says Peter Norton, who wrote Fighting Traffic: The Dawn of the Motor Age in the American City. “It’s a different mental model of what a street is for.”

To the average city dweller in the early 20th century, the idea of a city oriented around private cars would have been incomprehensible.

For cars to become common, that model had to change. Motorists—car dealers and manufacturers, and associations of wealthy car owners—united as an interest group. They conducted public information campaigns, teaching people how to cross streets safely and in the process normalizing the idea that streets belonged to cars. The modern use of the term “jaywalking,” which originally referred to rural visitors walking obliviously in big-city streets, dates to propaganda campaigns during the 1910s. With transcendent marketing insight, motorists realized the best way to discredit the streets-are-for-walking crowd was to make them look uncool. (“Jay” is an old-timey term for an inexperienced person; in other words, a rube.)

Public relations and mental models aside, another problem remained: the streets themselves. In cities, they were made of dirt or gravel. That would change as a consequence of waste—but not, as one might expect, waste in the form of horse manure. Both Norton and Wells offer an alternative take on that problem, contextualizing horse dung as a relatively minor component of a much deeper waste problem. To put it in perspective: For most of the late 19th century, even as America’s largest cities doubled in population, municipal garbage collection didn’t yet exist, much less environmental regulations. In New York City, street cleaning dates to 1895; the concept of a “sanitary landfill” was developed in Great Britain in the 1920s, and took a few more decades to become popular in the United States.

Factories and businesses disposed of wastes in local waterways or, if it was more convenient, empty lots. People tended to live near where they worked, and they generated their own waste too. Household refuse was thrown into gutters, and human waste ended up in waterways and local cesspits. Tenements truly overflowed. Cities were, in short, hellholes. As much as they praised any automaker, urban citizens of the late 19th century celebrated sanitation engineers.

Driverless cars, currently the darling of Silicon Valley, are a cosmetic upgrade on the status quo, promoted as revolutionary, but likely changing little.

To install modern sewer systems—which usually just diverted waste to local lakes and rivers and coastlines—streets were torn up. Afterward it made sense to rebuild them with asphalt, a natural form of petroleum, which inventors had learned to use as a glue to bind gravel into hard, smooth surfaces. These were easier to clean, and also better for cars. Streetcars now had to compete on roads suited to automobiles, and it wasn’t a fair fight.

Cars clogged the streets, slowing traffic and preventing streetcars from keeping their schedules. Ridership fell. Streetcar companies struggled to stay profitable, all the more so because, as local monopolies, city governments limited fare increases. Rising coal prices hurt them further. By the time car manufacturers bankrolled the purchase of streetcar companies between the late 1930s and early 1950s, an episode sometimes seen as evidence of a streetcar-killing business conspiracy, those companies were already going bankrupt.

Only then could the 20th century of automobile dominance proceed in the manner we now take for granted. And even that required massive government investments in highways—by 1929, state gas taxes, which funded roads, were collected in all 48 states and D.C.—and municipal codes that separated residences from businesses and made off-street parking a business requirement.

Not until after World War II did the idea of personal car ownership as both normal and necessary triumph. In fact, the popular phrase “America’s love affair with cars,” was actually coined in 1961 by television copywriters at DuPont, a major General Motors investor, just as critics were starting to decry pollution and traffic congestion and the dehumanizing effects of car-oriented planning.

What might be learned and applied to our own automobile-troubled historical moment? The foremost lesson, say historians Wells and Norton, is that the march of progress is neither straight nor technologically preordained. Even with urban streets paved, for example, country roads remained an impassable mess, a problem that farmers were in no hurry to fix with their own tax dollars. Changing that would require convincing them that smooth roads were in the farmers’ own best interests, not just those of wealthy city car-owners. And personal automobiles aren’t much use without parking: Zoning codes requiring businesses to provide off-street parking are an unappreciated but crucial component of the modern landscape.

In short, the automobile didn’t arrive as an “environmental savior,” a solution to urban waste epitomized by horse manure in New York City streets. The poor horses, in fact, were only a small part of the problem. The car emerged with an orchestrated push by the auto industry, and its reign was paved by a rising demand for gasoline and government investment in highways, roads, and zoning regulations. Similarly it was a democratic drive, with legislation to follow, that gave us sanitation laws and cleaned up our streets.

Looking ahead, the current unsustainability of our automobile love won’t emerge from technological engineering, but social engineering, too. Historians Wells and Norton both view driverless cars, currently the darling of Silicon Valley, as a cosmetic upgrade on the status quo, promoted as revolutionary, but likely changing little. In a real revolution, they say, driverless cars would be one of many transportation options, along with bicycles, buses, and rail, in greener, saner, non-auto-centric future cities.

Of course, the social change required to revolutionize transportation under the current rule of the car will be formidable. Habits do change, though, and so do societies. “A lot of assumptions we treat as laws of nature are inventions,” says Norton. “A lot of mental models we think can’t change, can change. The proof is that they’ve changed in the past.”

Brandon Keim is a freelance journalist specializing in science, environment, and culture.

Lead photograph by Byron Company / Museum of the City of New York. A view of horse and cart congestion Hudson St. looking north from Duane St., 1898.