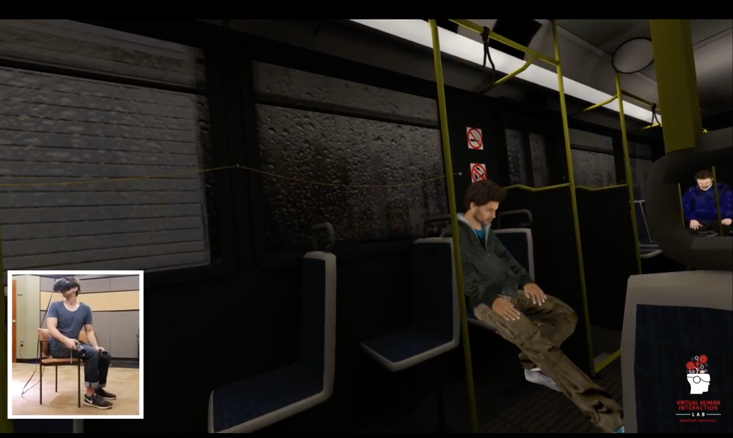

You wake up on a bus, surrounded by all your remaining possessions. A few fellow passengers slump on pale blue seats around you, their heads resting against the windows. You turn and see a father holding his son. Almost everyone is asleep. But one man, with a salt-and-pepper beard and khaki vest, stands near the back of the bus, staring at you. You feel uneasy and glance at the driver, wondering if he would help you if you needed it. When you turn back around, the bearded man has moved toward you and is now just a few feet away. You jolt, fearing for your safety, but then remind yourself there’s nothing to worry about. You take off the Oculus helmet and find yourself back in the real world, in Jeremy Bailenson’s Virtual Human Interaction Lab at Stanford University.

For more and more people in Silicon Valley, a long and dangerous bus ride isn’t a simulation; it’s reality. Santa Clara County—home to Facebook and Google—contains the nation’s second highest concentration of affluence. The soaring cost of living here has displaced all but the wealthiest. In Palo Alto, the nation’s tech epicenter, the number of homeless people has increased by a staggering 26 percent in the past two years, with higher concentrations of children and families among them. They turn to shelters, campers, and, in harder times, bus line 22.

Just a mile from Stanford’s bucolic campus, the 22 departs Palo Alto for San Jose, and shuttles between the two cities all night. Silicon Valley’s homeless have taken to it for safety and shelter so often and in such numbers that it’s been dubbed Hotel 22. Dozens of people shuffle on past midnight, in an orderly, exhausted procession. They take the 90-minute ride from one end of its route to the other, get off, and then get right back on. Drivers on line 22 know the drill. After leaving the first station, one announces over the bus’s intercom, “No lying down, no putting your feet on the seats … Be respectful to the next people getting on because they’re going to work. Let’s have a nice safe ride; let’s do it right. Anybody wants to act up, well, you know the consequences.”

On Palo Alto’s El Camino Real, 2019 Tesla coupes sit in a dealership, waiting to be scooped up by new multimillionaires. Down the road, rows of RVs are parked for days on end, housing families whose lives were upended weeks or months ago. When we’re no longer shocked by juxtapositions like these, it means we have gone blind to the suffering of homeless people. Sometimes we fail to see their humanity at all. In one study, neuroscientists showed people images of individuals from many groups—businesspeople, athletes, parents—while scanning their brains with fMRI. Parts of the brain associated with empathy were activated by every group except the homeless.

Empathy evolved as one of humans’ vital survival skills. Over millennia, we changed to make connecting easier. Our testosterone levels dropped, our faces softened, and we became less aggressive. We developed larger eye whites than other primates, so we could easily track one another’s gaze, and intricate facial muscles that allowed us to better express emotion. Our brains developed to give us a more precise understanding of each other’s thoughts and feelings.

As a result, we developed vast empathic abilities. We can travel into the minds of not just friends and neighbors but also enemies, strangers, and even imaginary people in films or novels. This helped us become the kindest species on Earth. Chimpanzees, for instance, work together and console each other during painful moments, but their goodwill is limited. They rarely give each other food, and though they may be kind to their troop, they are vicious outside of it.

By contrast, humans are world-champion collaborators, helping each other far more than any other species. This became our secret weapon. As individuals, we were not much to behold, but together, we were magnificent—unbeatable super-organisms who hunted woolly mammoths, built suspension bridges, and took over the planet.

The average person in 2009 was less empathic than 75 percent of people in 1979.

The modern world has made kindness harder. In 2007, humanity crossed a remarkable line: For the first time, more people lived in cities than outside of them. By 2050, two-thirds of our species will be urban. Yet we are increasingly isolated. In 1911, about 5 percent of British citizens lived alone; a century later that number was 31 percent. Solo living has risen most among young people—in the United States, ten times as many 18- to 34-year-olds live alone now than in 1950—and in urban centers. More than half of Paris’s and Stockholm’s residents live alone, and in parts of Manhattan and Los Angeles that number is north of 90 percent.

As cities grow and households shrink, we see more people than ever before, but know fewer of them. Rituals that bring us into regular contact—attending church, participating in team sports, even grocery shopping—have given way to solitary pursuits, often carried out over the Internet. At a corner store, two strangers might make small talk about basketball, school systems, or video games, getting to know all sorts of details about each other. Online, the first thing we encounter about a person is often the thing we’d like least about them, such as an ideology we despise. They are enemies before they have a chance to be people.

If you wanted to design a system to break empathy, you could scarcely do better than the society we’ve created. And in some ways, empathy has broken. Many scientists believe it’s eroding over time. For the past four decades, psychologists have measured empathy. The news is not good. Empathy has dwindled steadily, especially in the 21st century. The average person in 2009 was less empathic than 75 percent of people in 1979.

Modern society is built on human connection, and our house is teetering. For the past dozen years, I’ve researched how empathy works and what it does for us. But being a psychologist studying empathy today is like being a climatologist studying the polar ice: Each year we discover more about how valuable it is, just as it recedes all around us. Does it have to be this way?

Homeless individuals present one of empathy’s most difficult tests. Acknowledging their experiences is painful; it induces guilt; it damages our sense that the world is just. Circumstances like these tip the balance in empathy’s tug-of-war, favoring avoidance. At Stanford, Jeremy and I set out to investigate whether we could use immersive technology to make caring about forgotten people easier, more natural, or even inescapable.

A few decades ago, the technology in Jeremy’s lab existed only in science fiction. A few years ago, it was exclusive, expensive, and glitchy, an exciting idea with little useful execution. Then it exploded. In 2014, Facebook acquired Oculus VR for about $2 billion. At the same time a raft of cheap, portable devices, ranging from $10 to $300, made virtual reality accessible to the average person. According to Jeremy, this is no incremental shift in the media landscape. “VR is far more psychologically powerful than any medium ever invented,” he writes. Its secret sauce is what Jeremy calls “psychological presence.” Books and movies transport us into their stories, but readers and viewers remain aware that they are reading and viewing. VR envelops people so completely that they forget it is media at all. When people are immersed in VR, their hearts race as they fly over a city, they jump to avoid falling debris or enemy fire. They confuse virtual experiences for real ones, which makes sense, because those experiences are quite real to them.

VR enhances fantasy and will almost certainly define the future of gaming and pornography. But psychological presence can also allow us to try on real experiences. According to Jeremy, this is where the technology’s true power lies. Quarterbacks use it to better visualize the field, and medical students use it to practice complicated procedures. In both cases, VR facilitates quick, deep learning. VR also allows people to see themselves in the body of an elderly adult or person of another race, or through the eyes of a colorblind person. As Jeremy and his colleagues have found, these experiences decrease stereotyping and discrimination.

Findings like these led the artist Chris Milk to celebrate VR as “the ultimate empathy machine.” In 2014, Milk created Clouds Over Sidra, a VR film that tells the story of a 12-year-old girl in the Za’atari camp in Jordan, home to about 84,000 Syrian refugees at the time. Viewers “meet” Sidra and spend time with her and her family, exploring the camp along the way. Milk recently brought the film—and the Oculus headsets necessary to watch it—to the Davos World Economic Forum in Switzerland.

“These are people,” he reflects, “who might not otherwise be sitting in a tent in a refugee camp … but one afternoon in Switzerland, they all found themselves there.” According to Milk, “being there” mattered. He described why in a recent talk: “You’re not watching it through a television screen … You’re sitting there with her. When you look down, you’re sitting on the same ground that she’s sitting on. And because of that, you feel her humanity in a deeper way. You empathize with her in a deeper way.”

The idea is simple and powerful. Yes, technology can make it harder for us to see one another. But used differently, it can do just the opposite.

We can travel into the minds of others. This helped us become the kindest species on Earth.

Milk’s video makes for a powerful story, but few experiments have examined whether immersive technology actually builds empathy, and there are reasons to doubt. Imagine telling someone they have the chance to spend an hour inside the world of a refugee. Who would agree, and who would avoid it? Chances are, people who don’t want to empathize wouldn’t want to enter an “empathy machine” at all. VR might make already caring people care a tiny bit more. The question is whether it can do better than that.

About three years ago, Jeremy and I, along with our students Fernanda Herrera and Erika Weisz, decided to find out. We designed a VR experience to help Bay Area residents see their homeless neighbors in a new light. Using an Oculus Rift, viewers explored scenes that told the story of one person’s descent into homelessness. A viewer first “wakes up” in his apartment, facing eviction, and is asked to take inventory of furniture he can sell to keep afloat. That fails, and the viewer finds himself living in his car. A police officer catches him staying there illegally and impounds the vehicle, and the viewer ends up on Hotel 22. In this last scene, he can also learn about his fellow passengers. If he “clicks” on the father and son next to him, a narrator explains, “This is a father, Ray, and his son, named Ethan. Ethan’s mother suffered from a chronic illness and recently passed away. Left with the hospital bills, Ray is in debt. They’re on a family shelter waiting list. So until free spaces become available, they sleep on the bus at night.”

Jeremy and I were confident that people would feel empathy after walking around in a homeless person’s virtual life. But would VR build more empathy than traditional approaches? To test this, we assigned some people to complete our VR exercise, and others to read the same story—eviction, impoundment, Hotel 22—while imagining what the protagonist would think and feel. This kind of perspective-taking exercise has successfully increased empathy in dozens of studies, meaning that in ours, VR had real competition. When we began the project, I bet Jeremy that VR wouldn’t make people feel any more empathy than a low-tech alternative.

I was wrong. At first, both exercises increased people’s empathy for the homeless, and even their willingness to donate money to local shelters. But when we tested their caring more strenuously, differences emerged. We told participants about Proposition A, a ballot measure that would expand the Bay Area’s affordable housing initiative and also slightly increase taxes. People across our experiment said they supported the measure, but when we offered them the chance to sign a petition in support of it, those who had completed VR were more likely to agree. The technology also created longer-lasting empathy. A month after taking part in our study, participants who had undergone VR remained supportive of ballot initiatives to support the homeless and were less likely than other participants to dehumanize them.

Neither Jeremy nor I believe that VR is the perfect empathy machine. Some experiences simply cannot be mimicked. We can put someone on Hotel 22 for a few minutes, but we can’t make them feel the grinding desperation of long-term hunger. Nonetheless, we’re optimistic that VR can raise people’s curiosity—driving them to learn more about people they’d otherwise ignore. Jeremy and his team have installed our Hotel 22 experience in malls and museums around the Bay Area, where thousands of people have tried it. In To Kill a Mockingbird, Atticus Finch advises Scout, “You never really understand a person until you consider things from his point of view … until you climb into his skin and walk around in it.” As VR becomes more commonplace, millions of people will have the chance to do just that.

Jamil Zaki is an associate professor of psychology at Stanford University and head of the Stanford Social Neuroscience Laboratory. He is author of the forthcoming book, The War for Kindness.

From the book The War for Kindness: Building Empathy in a Fractured World by Jamil Zaki. Copyright © 2019 by Jamil Zaki. Published by Crown, an imprint of Random House, a division of Penguin Random House LLC. All rights reserved.

Lead image credits: AndyPositive; Chanyanuch Wannasinlapin / Shutterstock