The contrast could not have been starker—here was one of the world’s most revered figures, His Holiness the Fourteenth Dalai Lama, expressing his belief that all life is sentient, while I, as a card-carrying neuroscientist, presented the contemporary Western consensus that some animals might, perhaps, possibly, share the precious gift of sentience, of conscious experience, with humans.

The setting was a symposium between Buddhist monk-scholars and Western scientists in a Tibetan monastery in Southern India, fostering a dialogue in physics, biology, and brain science.

Buddhism has philosophical traditions reaching back to the fifth century B.C. It defines life as possessing heat (i.e., a metabolism) and sentience, that is, the ability to sense, to experience, and to act. According to its teachings, consciousness is accorded to all animals, large and small—human adults and fetuses, monkeys, dogs, fish, and even lowly cockroaches and mosquitoes. All of them can suffer; all their lives are precious.

Compare this all-encompassing attitude of reverence to the historic view in the West. Abrahamic religions preach human exceptionalism—although animals have sensibilities, drives, and motivations and can act intelligently, they do not have an immortal soul that marks them as special, as able to be resurrected beyond history, in the Eschaton. On my travels and public talks, I still encounter plenty of scientists and others who, explicitly or implicitly, hold to human exclusivity. Cultural mores change slowly, and early childhood religious imprinting is powerful.

I grew up in a devout Roman Catholic family with Purzel, a fearless dachshund. Purzel could be affectionate, curious, playful, aggressive, ashamed, or anxious. Yet my church taught that dogs do not have souls. Only humans do. Even as a child, I felt intuitively that this was wrong; either we all have souls, whatever that means, or none of us do.

René Descartes famously argued that a dog howling pitifully when hit by a carriage does not feel pain. The dog is simply a broken machine, devoid of the res cogitans or cognitive substance that is the hallmark of people. For those who argue that Descartes didn’t truly believe that dogs and other animals had no feelings, I present the fact that he, like other natural philosophers of his age, performed vivisection on rabbits and dogs. That’s live coronary surgery without anything to dull the agonizing pain. As much as I admire Descartes as a revolutionary thinker, I find this difficult to stomach.

Modernity abandoned the belief in a Cartesian soul, but the dominant cultural narrative remains—humans are special; they are above and beyond all other creatures. All humans enjoy universal rights, yet no animal does. No animal possesses the fundamental right to its life, to bodily liberty and integrity.

Yet the same abductive inference used to infer experience in other people can also be applied to nonhuman animals. I am confident in abducing experiences in fellow mammals for three reasons.

First, all mammals are closely related, evolutionarily speaking. Placental mammals trace their common descent to small, furry, nocturnal creatures that scurried the forest in search of insects. After an asteroid killed off most of the remaining dinosaurs about 65 million years ago, mammals diversified and occupied all those ecological niches that were swept clean by this planet-wide catastrophe.

My church taught that dogs do not have souls. Only humans do. Even as a child, I felt this was wrong.

Modern humans are genetically most closely linked to chimpanzees. The genomes of these two species, the instruction manual for how to assemble these creatures, differ by only one out of every hundred words. We’re not that different from mice either, with almost all mouse genes having a counterpart in the human genome. Thus, when I write “humans and animals,” I simply respect dominant linguistic, cultural, and legal customs in differentiating between the two natural kinds, not because I believe in the non-animal nature of humans.

Second, the architecture of the nervous system is remarkably conserved across all mammals. Most of the close to 900 distinct annotated macroscopic structures found in the human brain are present in the mouse brain, the animal of choice for experimentalists, even though it is a thousand times smaller.

It is not easy, even for a neuroanatomist armed with a microscope, to distinguish human nerve cells from their murine counterpart, once the scale bar has been removed. That’s not to say human neurons are the same as mouse neurons—they are not; the former are more complex, have more dendritic spines, and look to be more diverse than the latter. The same story holds at the genomic, synaptic, cellular, connectional, and architectural levels—we see a myriad of quantitative but no qualitative differences between the brains of mice, dogs, monkeys, and people. The receptors and pathways that mediate pain are analogous across species.

The human brain is big, but other creatures, such as elephants, dolphins, and whales, have bigger ones. Embarrassingly, some not only have a larger neocortex but also one with twice as many cortical neurons as humans.

Third, the behavior of mammals is kindred to that of people. Take my dog Ruby—she loves to lick the remaining cream off the whisk I use to whip heavy cream by hand—no matter where she is in the house or garden she comes running in as soon as she hears the sounds of the metal wire loops striking the glass. Her behavior tells me that she enjoys the sweet and fatty whipping cream as much as I do; I infer that she has a pleasurable experience. Or when she yelps, whines, gnaws at her paw, limps, and then comes to me, seeking aid: I infer that she’s in pain because under similar conditions I act similarly (sans gnawing). Physiologic measures confirm this inference: dogs, just like people, have an elevated heart rate and blood pressure and release stress hormones into their bloodstream when in pain. Dogs not only experience pain from physical injuries but can also suffer, for example if they are beaten or otherwise abused or when an older pet is separated from its litter mate or its human companion. This is not to argue that dog-pain is identical to people-pain; it is not. But all the evidence is compatible with the supposition that dogs, and other mammals, not only react to noxious stimuli but also experience the awfulness of pain and suffering.

As I write, the world is witnessing a killer whale carrying her baby calf, born dead, for more than two weeks and a thousand miles across the waters of the Pacific Northwest. As the corpse of the baby orca keeps on falling off and sinking, the mother has to expend considerable energy to dive after it and retrieve it, an astonishing display of maternal grief.

Monkeys, dogs, cats, horses, donkeys, rats, mice, and other mammals can all be taught to respond to forced-choice experiments—modified from those used by people to accommodate paws and snouts, and using food or social rewards in lieu of money. Their responses are remarkably similar to the way people behave, once differences in their sensory organs are accounted for.

The most obvious trait that distinguishes humans from other animals is language. Everyday speech represents and communicates abstract symbols and concepts. It is the bedrock of mathematics, science, civilization, and all of our cultural accomplishments.

Many classical scholars assign to language the role of kingmaker when it comes to consciousness. That is, language use is thought to either directly enable consciousness or to be one of the signature behaviors associated with consciousness. This draws a bright line between animals and people. On the far shore of this Rubicon live all creatures, small and large—bees, squids, dogs, and apes; while they have many of the same behavioral and neuronal manifestations of seeing, hearing, smelling, and experiencing pain and pleasure that people have, they have no feelings. They are mere biological machines, devoid of any inner light. On the near shore of this Rubicon lives a sole extant species, Homo sapiens. Somehow, the same sort of biological stuff that makes up the brains of creatures across the river is superadded with sentience (Descartes’s res cogitans or the Christian soul) on this side of the Rubicon.

There are other cognitive differences between people and mammals: We can be deliberately cruel.

One of the few remaining contemporary psychologists who denies the evolutionary continuity of consciousness is Euan Macphail. He avers that language and a sense of self are necessary for consciousness. According to him, neither animals nor young children experience anything, as they are unable to speak and have no sense of self—a remarkable conclusion that must endear him to parents and pediatric anesthesiologists everywhere.

What does the evidence suggest? What happens if somebody loses their ability to speak? How does this affect their thinking, sense of self, and their conscious experience of the world? Aphasia is the name given to language disorders caused by limited brain damage, usually but not always to the left cortical hemisphere. There are different forms of aphasia—depending on the location of the damage, it can affect the comprehension of speech or of written text, the ability to properly name objects, the production of speech, its grammar, the severity of the deficit, and so on.

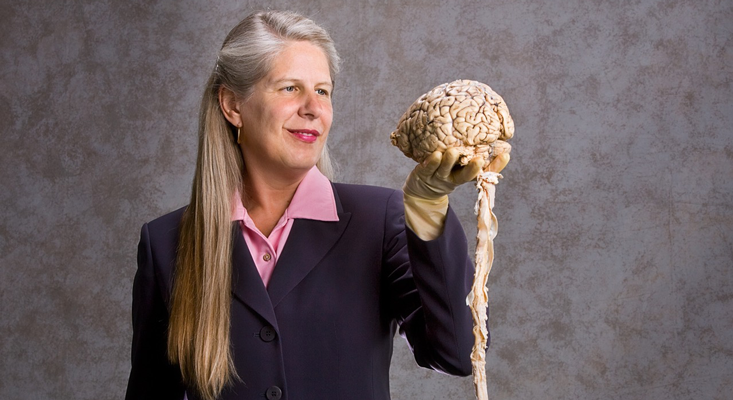

The neuroanatomist Jill Bolte Taylor rocketed to fame on the strength of her TED Talk and a subsequent bestselling book about her experience while suffering a stroke. At age 37, she suffered a massive bleeding in her left hemisphere. For the next several hours, she became effectively mute. She also lost her inner speech, the unvoiced monologue that accompanies us everywhere, and her right hand became paralyzed. Taylor realized that her verbal utterances did not make any sense and that she couldn’t understand the gibberish of others. She vividly recalls how she perceived the world in images while experiencing the direct effect of her stroke, wondering how to communicate with people. Hardly the actions of an unconscious zombie.

Two objections to Taylor’s compelling personal story is that her narrative can’t be directly verified—she suffered the stroke at home, alone—and that she reconstructed these events months and years after the actual episode. Consider then the singular case of a 47-year-old man with an arteriovenous malformation in his brain that triggered minor sensory seizures. As part of his medical workup, regions in his left cerebral hemisphere were anesthetized by a local injection. This led to a dense aphasia, lasting for about 10 minutes, during which he was unable to name animals, answer simple yes/no questions, or describe pictures. When asked to write down immediately afterward what he recalled, it became apparent that he was cognizant of what was happening:

In general my mind seemed to work except that words could not be found or had turned into other words. I also perceived throughout this procedure what a terrible disorder that would be if it were not reversible due to local anesthetics. There was never a doubt that I would be able to recall what was said or done, the problem was that I often could not do it.

He correctly recalled that he saw a picture of a tennis racket, recognized it for what it was, making the gesture of holding a racket with his hand and explaining that he had just bought a racket. Yet in actuality all he said was “perkbull.” What is clear is that the patient continued to experience the world during his brief aphasia. Consciousness did not fade with the degradation of his or Jill Taylor’s linguistic skills.

The belief that only humans experience anything is preposterous, a remnant of an atavistic desire.

There is ample evidence from split-brain patients that consciousness can be preserved in the nonspeaking cortical hemisphere, usually the right one. These are patients whose corpus callosum has been surgically cut to prevent aberrant electrical activity from spreading from one to the other hemisphere. Almost half a century of research demonstrates that these patients have two conscious minds. Each cortical hemisphere has its own mind, each with its own peculiarities. The left cortex supports normal linguistic processing and speech; the right hemisphere is nearly mute but can read whole words and, in some cases at least, can understand syntax and produce simple speech and song.

It could be countered that language is necessary for the proper development of consciousness but that once this has taken place, language is no longer needed to experience. This hypothesis is difficult to address comprehensively, as it would require raising a child under severe social deprivation.

There are documented cases of feral children who either grew up in near total social isolation or who lived with groups of nonhuman primates, wolfs or dogs. While such extreme abuse and neglect leads to severe linguistic deficits, it does not deprive these wild children of experiencing the world, usually in a tragic and, to them, incomprehensible, manner.

Finally, to restate the obvious—language contributes massively to the way we experience the world, in particular to our sense of the self as our narrative center in the past and present. But our basic experience of the world does not depend on it.

Besides true language, there are, of course, other cognitive differences between people and the rest of mammals. Humans can organize into vast and flexible alliances to pursue common religious, political, military, economic, and scientific projects. We can be deliberately cruel. Shakespeare’s Richard III spits out:

“No beast so fierce but knows some touch of pity. But I know none, and therefore am no beast.”

We can also introspect, second-guessing our actions and motivations. As we grow up, we acquire a sense of mortality, a knowledge that our life has a finite horizon, the worm at the core of human existence. Death has no such dominion over animals.

The belief that only humans experience anything is preposterous, a remnant of an atavistic desire to be the one species of singular importance to the universe at large. Far more reasonable and compatible with all known facts is the assumption that we share the experience of life with all mammals.

Christof Koch is the president and chief scientist of the Allen Institute for Brain Science in Seattle, following 27 years as a professor at the California Institute of Technology. He is the author of Consciousness: Confessions of a Romantic Reductionist (MIT Press), The Quest for Consciousness: A Neurobiological Approach, and other books.

Excerpted from The Feeling of Life Itself: Why Consciousness Is Widespread but Can’t Be Computed by Christof Koch (The MIT Press, 2019).

Lead image: Benjavisa Ruangvaree Art / Shutterstock