Take a deep breath.

As you breathe in, your lungs fill with air. The air is carried through every part of your lungs by tubes. These tubes are organized in a particular way. They branch off, one into the left lung, one into the right. The tubes fill our lungs by branching, branching, and branching again, into tinier and tinier tubes. Each branching point is similar to the previous one. Your breath, your very life, depends on this structure. It is a structure organized by the principle of self-similarity.

Self-similarity is everywhere in nature. Look at a fern: Each fern leaf is composed of smaller replicas of itself, which are composed of yet smaller replicas. Or think of vast deltas, where huge rivers branch out into smaller and smaller streams and rivulets until they vanish into the earth or oceans. Each branching of a river is similar to a previous branching that created that river.

If you make up a sentence of any complexity, and search for that exact sentence on the Internet, it’s almost never there.

The Internet has, without anyone overseeing it, evolved into a self-similar pattern, with huge hubs connecting to smaller ones, these themselves connecting, in just the same way, to smaller hubs all the way down to phones and laptops.

Self-similarity is everywhere because it is efficient. If a tube, developing into a lung, or frond into a fern, does the same thing each time it grows, then the genes don’t need to specify the details of the growth. The same thing happens at the larger scale, and at the smaller. It makes no difference whether a river is the Amazon or a tiny stream, it branches in the same way.

Self-similarity is at the heart of language, too.

Sentences and phrases of human languages, all human languages, have an inaudible and invisible hierarchical structure. When we are children, we impose this structure on the sequences of sounds that we hear. Our minds can’t understand continuous streams of sound directly as meaningful language. Instead, we subconsciously chop them up into discrete bits—sounds and words—and organize these into larger units. This means that sentences have a hierarchical structure.

Other animals, even extremely intelligent close evolutionary relatives like bonobos and chimpanzees, treat sequences of words as sequences, not as hierarchies. The same is true for modern artificial intelligences based on deep learning. Humans, however, don’t seem to be able to do this. When we encounter language, the hierarchical structure of phrases and sentences is something our minds can’t escape from. We hear sounds or see signs, but our minds think syntax.

The most basic units of language, words and word-parts, are limited to the tens of thousands. We can create new ones on the fly if we need to, but we don’t have a distinct word for every aspect of our existence. The number of words speakers know is a finite store. We can add words to that store, and we can forget words. But the sentences we can say, or understand, are unlimited in number. They create meanings where there were none before.

Human language is amazingly creative. If you make up a sentence of any complexity, and search for that exact sentence on the Internet, it’s almost never there. Virtually everything we say is novel. Yet at the heart of this capacity of ours lies an incredibly simple piece of mental technology: Merge. Merge takes two bits of language, say two words, and creates out of them another bit of language. It builds the hierarchical structures of language.

Merge was proposed by Noam Chomsky in the early 1990s. He argued that this single piece of mental technology, plus language specific constraints that children could learn from their linguistic experiences, was enough to capture the syntax of all human languages.

Let’s take two words, drink and wine. Merge says that we can take these two bits of language and from these create a new bit of language. We don’t do this by putting the two words in a sequence, like an artificial intelligence or a bonobo would do. Instead we build a new hierarchical unit. This unit puts together the verb drink with the noun wine to create the phrase drink wine, with wine being the grammatical object of drink.

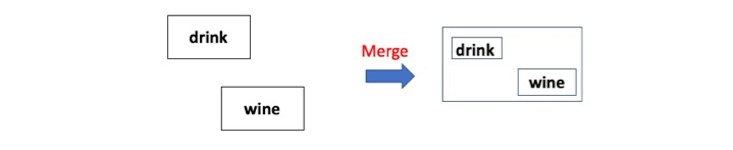

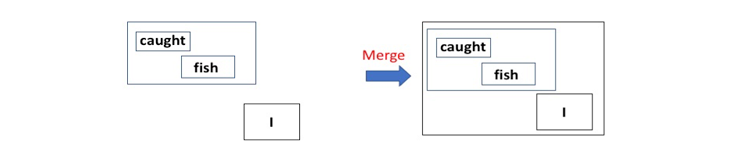

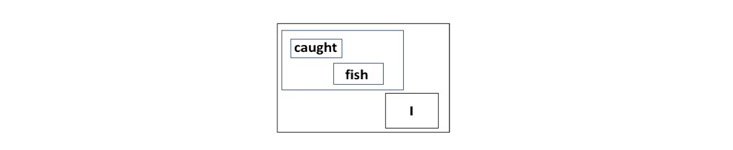

Let’s visualize how Merge works on a verb and its object by putting things in boxes. Each box is a bit of language. If you’re not in a box, you’re not a bit of language. The things inside boxes aren’t in a sequence; they don’t have an order. The only information the box adds is that the bits inside it are grouped together. The words drink and wine are bits of language, and Merge says that a grouping of these can also be a bit of language. We can represent this with boxes like this:

Merge has created a self-similar structure: a larger bit of language containing two smaller bits of language. Boxes within boxes. An invisible hierarchy.

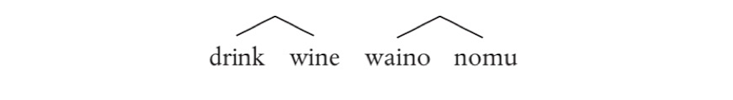

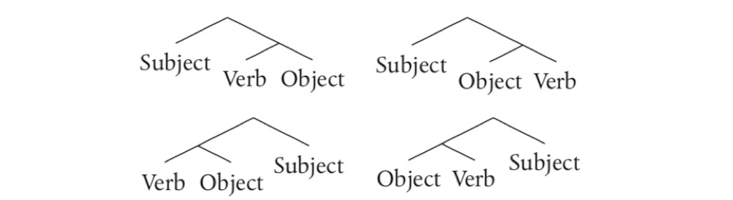

Now, in spoken or written language, we have to put one word after the other. That’s just the way these channels of language work. We can’t say two words at the same time. Speaking, and to a lesser extent signing, flattens the hierarchy that Merge builds into a sequence, and that sequence has an order. This means that this structure, which is just one structure as far as Merge is concerned, can be pronounced in two ways. We either pronounce it as wine drink, or as drink wine. The grammatical object either appears before the verb, or after it. Those are the only two logical possibilities. The first is the order we’d find in a language like Japanese, where we’d say waino nomu, literally wine drink. The second is, of course, English.

Linguists usually write the outcome of Merge using little tree diagrams. These tree diagrams give us the information that comes from Merge (what words group together), plus information about order. The diagrams for English and Japanese look like this:

These trees are the same in terms of Merge, but distinct in the order of their parts. We’ve translated the pure hierarchy that Merge gives us into an order that we can pronounce.

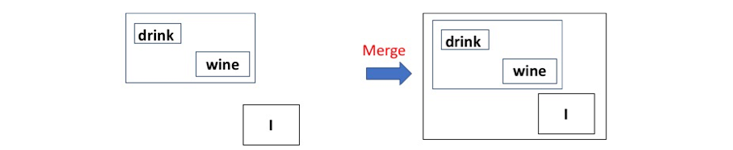

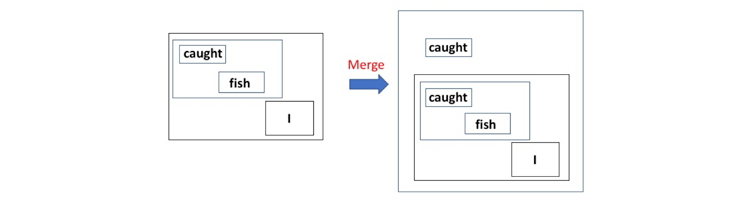

Let’s assume that I drink wine. To express this thought as a sentence, we want to add a grammatical subject to the bit of language we’ve just created. Since Merge says we can take two bits of language and create a new one, we can apply Merge to the word I and the linguistic unit we’ve just built:

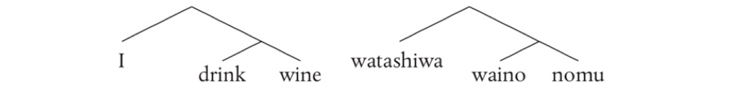

Now we have nested boxes. One big unit containing two smaller units, one of which is the result of a previous process of Merge. The Japanese word that best translates the English word I is watashiwa, so we can write our two trees like this:

English is a subject-verb-object language, while Japanese is a subject-object-verb language. But both are identical as far as Merge is concerned.

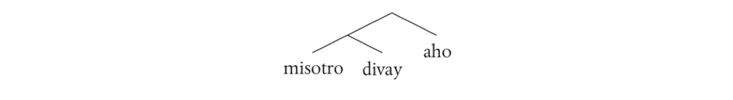

There are also languages that mix up these orders. Malagasy, for example, has the English order for drink wine, but puts the subject after that unit:

misotro divay aho

drink wine I

The Merge structure for Malagasy is just the same as that for English or Japanese, but while those languages put the subject first, Malagasy puts it last.

The last logical possibility is where we say the equivalent of wine drink I to mean I drink wine.

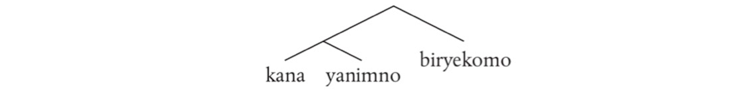

This is pretty exotic in the world’s languages. In fact, for many years, linguists were unable to find a language where that was the natural order to express this thought. However, during the 1960s and early ’70s, the late Desmond Derbyshire lived in the Amazonian village of Kasawa in Brazil. There he worked on learning and analyzing the language of a local tribe, the Hixkaryana. As Derbyshire worked on the language, he discovered that it had a basic order exactly the reverse of English. To express The boy caught a fish, the Hixkaryana said the equivalent of A fish caught the boy:

kana yanimno biryekomo

fish he-caught-it boy

Since Derbyshire’s work, a number of other languages with this order, the object-verb-subject order, have come to light. Even these rare languages can be thought of as having the same structure, given by Merge:

Hixkaryana has the Japanese order for the most deeply embedded unit, giving kana yanimno (literally fish caught). But it has the Malagasy order for the subject biryekomo, “boy.” The whole sentence can be given a tree diagram that looks like this:

Merge isn’t very complex, but it does a lot of what linguists need it to do. It applies to discrete units of language (words or their parts). It combines these, not sequentially, but hierarchically. It doesn’t state what order the words have to be pronounced in, so it allows variation across languages. The hierarchical structure is the same in all four types of language we just looked at, but the order of the corresponding words is different.

Self-similarity is everywhere because it is efficient.

The fact that the hierarchical structure is the same but the word order is different allows us to express an important idea. The way that languages build up meaning is through Merge. Each Merge comes along with an effect on the meaning of the sentence, and that effect is generally both stable and systematic. That’s why it makes sense to say that the Japanese and English sentences mean the same. They have different orders, but there is a deep commonality. Merge builds both structure and meaning in the same basic way in both kinds of language. Languages are deeply similar, not deeply different.

Merge is also open-ended. As we just saw, it can reuse something it has already created.

Because Merge reuses its own output, it is a recursive process. Recursive processes are well known in mathematics, and form the foundation of modern theories of computing. Merge is a quite specific recursive process—it uses exactly two units and it creates structures that are linguistic. If our human sense of linguistic structure is guided by Merge, that will explain why all human languages are hierarchical and none are sequential. It also explains why human language is so unbounded, why sentences don’t have a natural upper limit. Merge both creates, and limits, the infinite potential of language.

I said that the four types of languages we’ve just seen were the four logical possibilities given Merge. But there’s an apparent problem. There are other kinds of word order: two important ones are verb-subject-object, and object-subject-verb languages. In fact, verb-subject-object is fairly common. It’s the order found in Celtic languages like Scottish Gaelic, Mayan languages like Chol, and some Polynesian languages like Hawaiian.

Let’s look at Gaelic. In this language, to say “A boy caught a fish,” we say:

Ghlac balach iasg

caught boy fish

We can’t get this order from Merge by just switching round the order of object and verb, or the order of the subject with the rest of the sentence. As we’ve seen, there are only four possibilities when we do that:

Merge doesn’t look powerful enough to get us all the orders we want. Was Chomsky wrong to suggest Merge was sufficient as the single way that all syntax is constructed?

It seems he wasn’t wrong. Remember that Merge takes two bits of language and creates a new bit of language. So far, we have just used Merge to take independent bits of language and put them together. That’s how we got to the structure we’ve so far used for English, Japanese, Malagasy, and Hixkaryana.

But Merge is recursive. It can go back and reuse something it’s already used. This means we can merge the bit of language containing the verb caught (that is, the box with caught inside it) with the bit of language containing everything else (that is, the large outside box). What we create is a new bit of language that contains the box with the verb in it, and the box containing that:

The verb caught here is both inside the box containing caught fish and inside a larger box that contains caught and a box containing everything else. It’s in two places at once. We’ve created a kind of loop in the structure. We didn’t have to extend Merge to do this. Merge has the consequence that we can reuse bits of language that have already been used.

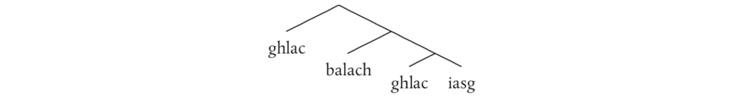

This gives us a way of understanding verb-subject-object languages like Gaelic: they involve this kind of loop. If I write the boxes as a tree diagram, putting things in the right order, we can begin to see the solution to our dilemma:

The subject here, balach, is “boy” and the object iasg is “fish.” The verb ghlac, “caught,” merges with its object and gives the meaning associated with catching fish. Then the result of that merges with the subject. This can be ordered as subject-verb-object, boy caught fish. Finally, Merge applies to a bit of language it has already used (the verb ghlac, “caught”) and merges that with the subject-verb-object unit. We can now pronounce this tree like this:

Ghlac balach ghlac iasg

caught boy caught fish

Oops! This isn’t quite what we want, since the verb (ghlac), “caught,” appears twice. That verb is just one bit of language, but it appears in two places, because we’ve reused it.

Common sense, though, might suggest that if you have one bit of language, you pronounce it just once. In Gaelic, when we reuse the verb, we pronounce it in its reused position. This is why in Gaelic we say Ghlac balach iasg, which is Caught boy fish.

Word order is, of course, far more complex than I’ve shown here. There are languages with very free word order, and even within languages there are many intriguing complexities. However, this idea, that Merge can both combine bits of language, and reuse them, gives us a unified understanding of how the grammar of human languages works.

Because Merge recursively builds hierarchies, with each application connecting to both meaning and sound, there is no end to the complexity of the meaningful structures it builds. Merge gives us the ability to build the new worlds of ideas that have been so central to the successes and disappointments of our species. It makes language unlimited.

David Adger is the author of Language Unlimited: The Science Behind Our Most Creative Power, which this article is adapted from. He is a professor of linguistics at Queen Mary University of London and the president of the Linguistics Association of Great Britain.

Read our interview with David Adger here.

Lead image: Inus / Shutterstock