The idea that humans should merge with AI is very much in the air these days. It is offered both as a way for humans to avoid being outmoded by AI in the workplace, and as a path to superintelligence and immortality. For instance, Elon Musk recently commented that humans can escape being outmoded by AI by “having some sort of merger of biological intelligence and machine intelligence.”1 To this end, he’s founded a company, Neuralink. One of its first aims is to develop “neural lace,” an injectable mesh that connects the brain directly to computers. Neural lace and other AI-based enhancements are supposed to allow data from your brain to travel wirelessly to one’s digital devices or to the cloud, where massive computing power is available.

For many transhumanists, uploading is key to the mind-machine merger.

Perhaps these sorts of enhancements will turn out to be beneficial, but to see if this is the case, we will need to move beyond all the hype. Policymakers, the public, and even AI researchers themselves need a better idea of what is at stake. For instance, if AI cannot be conscious, then if you substituted a microchip for the parts of the brain responsible for consciousness, you would end your life as a conscious being. You’d become what philosophers call a “zombie”—a nonconscious simulacrum of your earlier self. Further, even ifmicrochips could replace parts of the brain responsible for consciousness without zombifying you, radical enhancement is still a major risk. After too many changes, the person who remains may not even be you. Each human who enhances may, unbeknownst to them, end their life in the process.

To decide whether to enhance, you must understand the metaphysics of personal identity. Philosophers call the characteristics that a thing must have as long as it exists “essential properties.” What might your essential properties be? If you are simply the physical stuff that comprised your brain and body in first grade, you would have ceased to exist some time ago. That physical first-grader is simply not here any longer. Ray Kurzweil, in his 2005 book The Singularity Is Near: When Humans Transcend Biology, clearly appreciates the difficulties here, commenting:

So who am I? Since I am constantly changing, am I just a pattern? What if someone copies that pattern? Am I the original and/or the copy? Perhaps I am this stuff here—that is, the both ordered and chaotic collection of molecules that make up my body and brain.

Kurzweil is referring to two theories that are center stage in the age-old philosophical debate over the nature of persons. Key theories include the following:

1. The psychological continuity theory: You are essentially your memories and ability to reflect on yourself and, in its most general form, this type of view claims you are your overall psychological configuration, what Kurzweil referred to as your “pattern.”

2. Brain-based materialism: You are essentially the material that you are made out of (i.e., your body and brain)—what Kurzweil referred to as “the ordered and chaotic collection of molecules” that make up his body and brain.

3. The no-self view: The self is an illusion. The “I” is a grammatical fiction. There are bundles of impressions, but there is no underlying self. There is no survival because there is no person.

Each of these views has its own implications about whether to enhance. For instance, the psychological continuity view holds that enhancements can alter your substrate, but they must preserve your overall psychological configuration. This view would allow you to transition to silicon or some other substrate, at least in principle. In contrast, the brain-based materialism says that your thinking is dependent on the brain. Thought cannot “transfer” to a different substrate—enhancements must not change one’s material substrate, or the person would cease to exist.

On the no-self view, the survival of the person is not an issue, for there is no person or self there to begin with. In this case, expressions like “I” and “you” do not really refer to persons or selves. Notice that if you are a proponent of the no-self view, you may strive to enhance nonetheless. For instance, you might find intrinsic value in adding more superintelligence to the universe—you might value life forms with higher forms of consciousness and wish that your “successor” be such a creature.

I don’t know whether many of those who publicize the idea of a mind-machine merger, such as Elon Musk and Michio Kaku, have considered these classic positions on personal identity. But they should. It is a bad idea to ignore this debate. One could be dismayed, at some later point, to learn that a technology one advocated actually had a tremendously negative impact on human flourishing.

In any case, both Kurzweil and the philosopher Nick Bostrom have considered the issue in their work. They, like many other transhumanists, adopt a novel and intriguing version of the psychological continuity view; in particular, they adopt a computational, or patternist, account of continuity. Patternism’s point of departure is the computational theory of mind. Although computational theories of mind differ in their details, one thing they have in common is that they all explain cognitive and perceptual capacities in terms of causal relationships between components, each of which can be described algorithmically. One common way of describing the computational theory of mind is by reference to the idea that the mind is a software program: That is, the mind is the algorithm the brain implements, and this algorithm is something that different subfields of cognitive science seek to describe.

Each human who enhances may, unbeknownst to them, end their life in the process.

Those working on computational theories of mind in philosophy of mind tend to ignore the topic of patternism, as well as the more general topic of personal identity. This is unfortunate for two reasons. First, on any feasible view of the nature of persons, one’s view of the nature of mind plays an important role. For what is a person if not, at least in part, that which she thinks and reflects with? Second, whatever the mind is, an understanding of its nature should include the study of its persistence, and it seems reasonable to think that this sort of undertaking would be closely related to theories of the persistence of the self or person. Yet the issue of persistence is often ignored in discussions of the nature of the mind. I suspect the reason is simply that work on the nature of the mind is in a different subfield of philosophy from work on the nature of the person—a case, in other words, of academic pigeonholing.

To their credit, transhumanists step up to the plate in trying to connect the topic of the nature of the mind with issues regarding personal identity, and they are clearly right to sense an affinity between patternism and the Software Approach to the Mind. After all, if you take a computational approach to the nature of mind, it is natural to regard persons as being somehow computational in nature and to ponder whether the survival of a person is somehow a matter of the survival of their software pattern. The guiding conception of the patternist is aptly captured by Kurzweil:

The specific set of particles that my body and brain comprise are in fact completely different from the atoms and molecules that I comprised only a short while ago. We know that most of our cells are turned over in a matter of weeks, and even our neurons, which persist as distinct cells for a relatively long time, nonetheless change all of their constituent molecules within a month. … I am rather like the pattern that water makes in a stream as it rushes past the rocks in its path. The actual molecules of water change every millisecond, but the pattern persists for hours or even years.

According to the patternist, what is essential to you is your computational configuration: the sensory systems/subsystems your brain has (e.g., early vision), the association areas that integrate these basic sensory subsystems, the neural circuitry making up your domain-general reasoning, your attentional system, your memories, and so on. Together these form the algorithm that your brain computes.

You might think the transhumanist views a brain-based materialism favorably. Transhumanists generally reject brain-based materialism, however, because they tend to believe the same person can continue to exist if her pattern persists, even if she has “uploaded” to a computer, no longer having a brain. For many transhumanists, uploading is key to the mind-machine merger.

In the science-fiction novel Mindscan by Robert Sawyer, the protagonist Jake Sullivan has an inoperable brain tumor. Death could strike him at any moment. Luckily, Immortex has a new cure for aging and illness—a “mindscan.” Immortex scientists tell him they will upload his brain configuration into a computer and “transfer” it into an android body that is designed using his own body as a template. Although imperfect, the android body has its advantages—once an individual is uploaded, a backup exists that can be downloaded if one has an accident. And it can be upgraded as new developments emerge. Jake will be immortal.

Sullivan decides to get the mindscan. He enthusiastically signs numerous legal agreements. He is told that, upon uploading, his possessions will be transferred to the android, who will be the new bearer of his consciousness. Sullivan’s original copy, which will die soon anyway, will live out the remainder of his life on “High Eden,” an Immortex colony on the moon. Although stripped of his legal identity, the original copy will be comfortable there, socializing with the other originals who are also still confined to biological senescence.

Sawyer then depicts Jake’s perspective while lying in the scanning tube:

I was looking forward to my new existence. Quantity of life didn’t matter that much to me—but quality. And to have time—not only years spreading out into the future, but time in each day. Uploads, after all, didn’t have to sleep, so not only did we get all those extra years, we got one‐third more productive time. The future was at hand. Creating another me. Mindscan.

But then, a few seconds later:

“All right, Mr. Sullivan, you can come out now.” It was Dr. Killian’s voice, with its Jamaican lilt.

My heart sank. No …

“Mr. Sullivan? We’ve finished the scanning. If you’ll press the red button. …” It hit me like a ton of bricks, like a tidal wave of blood. No! I should be somewhere else, but I wasn’t. …

I reflexively brought up my hands, patting my chest, feeling the softness of it, feeling it raise and fall. Jesus Christ!

I shook my head. “You just scanned my consciousness, making a duplicate of my mind, right?” My voice was sneering. “And since I’m aware of things after you finished the scanning, that means I—this version—isn’t that copy. The copy doesn’t have to worry about becoming a vegetable anymore. It’s free. Finally and at last, it’s free of everything that’s been hanging over my head for the last twenty‐seven years. We’ve diverged now, and the cured me has started down its path. But this me is still doomed.”2

Sawyer’s novel is a reductio ad absurdum of the patternist conception of the person. All that patternism says is that as long as person A has the same computational configuration as person B, A and B are the same person. Indeed, Sugiyama, the person selling the mindscan to Jake, had espoused a form of patternism.2

But Jake has belatedly realized a problem with that view, which we shall call “the reduplication problem”: Only one person can really be Jake Sullivan. According to patternism, both creatures are Jake Sullivan, because they share the very same psychological configuration. But, as Jake learned, although the creature created by the mindscan process may be a person, it is not the same person as the original Jake. It is just another person with an artificial brain and body configured like the original. Both feel a sense of psychological continuity with the person who went into the scanner, and both may claim to be Jake, but nonetheless they are not the same person, any more than identical twins are.

Hence, having a particular type of pattern cannot be sufficient for personal identity. Indeed, the problem is illustrated to epic proportions later in Sawyer’s book when numerous copies of Sullivan are made, all believing they are the original!

But you may suspect that there still is a kernel of truth to patternism: Your cells change continually but your organizational pattern carries on. Your pattern is essential to yourself despite not being sufficient for a complete account of your identity. Perhaps there is an additional essential property which, together with your pattern, yields a complete theory of personal identity.

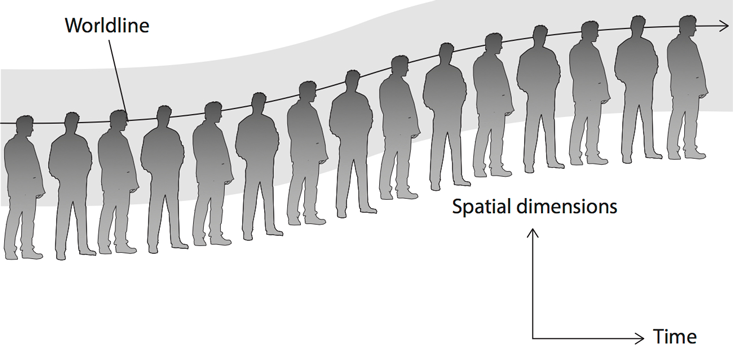

What could the missing ingredient be? Think about your own existence in space and time. When you go out to get the mail, you move from one spatial location to the next, tracing a path in space. A spacetime diagram can help us visualize the path one takes throughout one’s life. Collapsing the three spatial dimensions into one (the vertical axis) and taking the horizontal axis to signify time, consider the following typical trajectory:

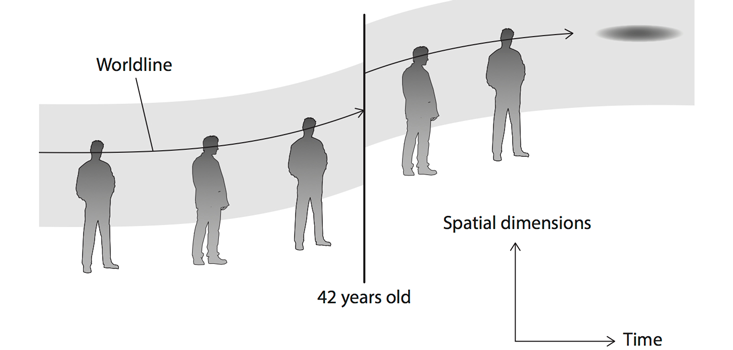

Notice that the figure carved out looks like a worm; you, like all physical objects, carve out a sort of “spacetime worm” over the course of your existence. This, at least, is the kind of path that ordinary people—those who are neither posthumans nor superintelligences—carve out. But now consider what happened during the mindscan. The copy’s spacetime diagram would look like the following:

This is bizarre. It appears that Jake Sullivan exists for 42 years, has a scan, and then somehow instantaneously moves to a different location in space and lives out the rest of his life. This alerts us that something is wrong with pure patternism: It lacks a requirement for spatiotemporal continuity. On the day of the mindscan, Jake went into the laboratory and had a scan; then he left the laboratory and went directly into a spaceship and flew to exile on the moon. It is this man—the one who traces a continuous trajectory through space and time—who is the true Jake Sullivan. The android is an unwitting impostor.

This response to the reduplication problem only goes so far, however. Consider Sugiyama, who, when selling his mindscan product, ventured a patternist pitch. If he had espoused patternism together with a spatiotemporal continuity clause, he would have to admit that his customers would not become immortal, and few would have signed up for the scan. That extra ingredient would rule out a mindscan (or any kind of uploading, for that matter) as a means to ensure survival. Only those wishing to have a replacement for themselves would sign up.

There is a general lesson here for the transhumanist: If one opts for patternism, enhancements like uploading are not really “enhancements”; they can even result in death.

Susan Schneider is the author of Artificial You: AI and the Future of Your Mind. She is the NASA-Baruch Blumberg Chair at the Library of Congress and the director of the AI, Mind and Society Group at the University of Connecticut. Her work has been explored on PBS, The History Channel, the National Geographic Channel, and featured by The New York Times, Science, and Smithsonian.

Excerpted from Artificial You: AI and the Future of Your Mind by Susan Schneider. Copyright © 2019 by Susan Schneider. Published by Princeton University Press. Reprinted by permission.

References

1. Solon, O. Elon Musk says humans must become cyborgs to stay relevant. Is he right? The Guardian (2017).

2. Sawyer, R. Mindscan Tor, New York, NY (2005).

Lead image: Zenzen / Shutterstock