Fishing for eels was a primal childhood experience for Patrik Svensson. On summer nights his father would take him down to a small stream near their home in Sweden. It was a magical place, surrounded by willow trees, with bats swooping through the moonlight. They barely talked as they set their fishing lines along the bank. “It was what me and my father did together. We fished for eels,” he recalls. Back home, Patrik’s mother would toss their catch in the frying pan, but the eels still squirmed and wriggled even after they were chopped up, with no heads. “I always found it fascinating and a little scary,” he says. “It made me think, what’s really the difference between life and death?”

That’s just one of the many questions that haunted Svensson for decades. And he’s far from alone in his obsession. The eel is one of the most mysterious creatures on Earth, and for centuries it confounded scientists, from Aristotle to Freud. No one could figure out how—or where—they reproduced. Or whether there were actually male and female eels. Or how they managed to transform from saltwater to freshwater animals and then back to saltwater “silver eels” at the end of their lives. Or even whether the eel was a fish or some kind of water snake.

Svensson, a soft-spoken journalist with a keen sense of wonder and a taste for philosophical musings, writes about his long fascination with this strange animal in The Book of Eels. A blend of natural history and memoir, the book is a beguiling chronicle of the many people who’ve tried to uncover the eel’s secrets.

I reached Svensson at his home in Malmo, Sweden.

What exactly is “the eel question”?

The eel has a very special scientific history. And it’s been such a big issue in natural science that the term “the eel question” refers to an especially hard mystery to solve. But the eel question has been different things over the years. From the beginning, it was, What is the eel? Is it a fish or something else? And then it had a lot to do with its sexuality. Does it have sexual differences? Are there males and females?

For centuries, no one could actually find any sexual organs. They couldn’t tell whether there were male and female eels.

Because no human being has ever seen eels breed, so to explain how they do it was an extremely hard question.

At one point, instead of eating, eels develop sexual organs.

To this day, no person has ever seen eels mate?

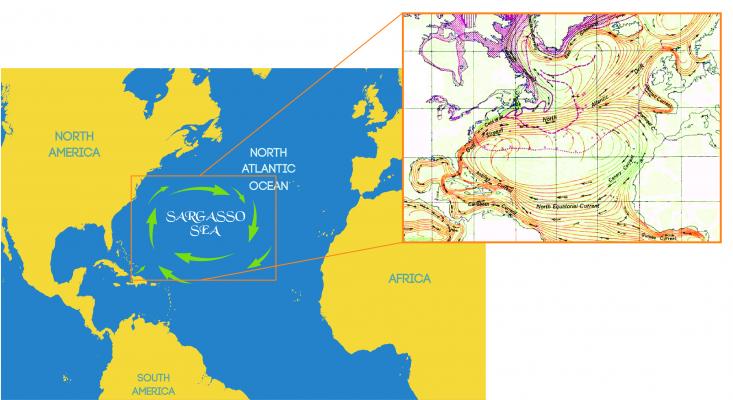

No one has ever seen it because all eels breed in the Sargasso Sea, a region in the Atlantic Ocean, and only there. Aristotle studied the eel and tried to explain how they breed. But when he dissected them he couldn’t find any sexual organs. And he came to the conclusion that eels don’t breed at all. He thought that the eel just came to life out of nothing, from the mud in the rivers and the seas. Carl Linnaeus came to the same conclusion as Aristotle—that they don’t breed and that there are no sexual differences between males and females. But there’s an explanation for that. Eels don’t develop their sexual organs until they are on the way back to the Sargasso Sea in just the last year of their life.

So every eel we might see in a river or pond in America or Europe has come from the Sargasso Sea?

Exactly. The American eel and the European eel are two different species, but they are very much alike. And both of them only breed in the Sargasso Sea.

Later, the young Sigmund Freud spent a summer trying to crack the eel mystery. Wasn’t he hunting for some evidence of testicles?

Yes, that’s an amazing story. Freud was 19 years old, studying natural science, and he wanted to solve the eel question. This was in the 1870s. By this time, they had found a female eel with eggs inside. So to solve the eel question, they had to find a male eel with sexual organs. Freud went to Trieste to find the eel testicle. That was like the holy grail of natural science at the time. He spent a month in Trieste and dissected over 400 eels.

He got the eels from fishermen?

Yeah, every morning he went down to the harbor and picked up a big basket of freshly caught eels. And then he went to his lab and cut them open for the whole day looking for the eel testicle. Of course, he didn’t find one testicle. And he had to write a report that concluded that he hasn’t been able to solve the eel question. I think it’s very funny to think about. This is the man who laid the basis for modern psychological therapy and the man who developed the theories about penis envy and castration anxiety. He started his scientific career by trying to explain the sexuality of a fish. And he failed.

No human being has ever seen eels breed.

Eventually, people discovered that eels metamorphosize into four completely different life stages. What are these different stages?

They’re born in the Sargasso Sea as a small larva. They have the shape of a willow leaf and drift with the ocean currents. The European eel is eastbound to Europe and the American eel to the west, and when they reach land, they develop into what we call the glass eel. They’re the same shape as an eel, but they’re totally transparent. Then they find their way up in rivers and seas and streams going into freshwater, and they go through another metamorphosis. They become what we call the yellow eel. And then they live for a very long time as yellow eels in freshwater.

Are yellow eels the ones we eat?

Mostly. Eels can live for a very long time, up to 85 years that we know for sure. But usually when they are 15 to 30 years old, they suddenly leave the freshwater and swim out in the ocean again and return to the Sargasso Sea. When they do this, they transform again and become what we call the silver eel. And this is a very strange creature. They stop eating completely for the whole trip back to the Sargasso Sea, which can take over a year. Instead of eating, they develop their sexual organs. Their eyes change, the way they swim changes. Their final goal is to return home to the place where they came from. And many people also like to eat this silver eel if they catch it in the ocean.

I’m still trying to wrap my head around how time factors into the life cycle of the eel. They might live in a pond for 50 years, and then they suddenly decide it’s time to swim back to the Sargasso Sea to reproduce. This is a very fluid sense of time.

It’s almost like time and aging are irrelevant for the eel. You know, if the eel can’t travel back to the Sargasso Sea, it never goes through the last metamorphosis. It doesn’t become sexually mature, and it seems like it can live almost forever in that stage. It’s like the eel can put a stop to its own aging. Some eels travel back to the Sargasso Sea after just five, six or seven years, and some eels travel back to the Sargasso Sea when they are 60 years old.

How do they know where to go—both as larvae and also as silver eels? In their first stage, they have to drift across the ocean. And somehow the European eel larvae go in one direction, while the American larvae go in a different direction.

That’s still one of the mysteries. Once they’re born, the European eel larvae just drift with the Gulf Stream to Europe. This can take two to three years. In the beginning, the American eel larvae are also drifting with the Gulf Stream, but then suddenly they leave the Gulf Stream and head west. How do they know where they are going? The scientific explanation is that there are some genetic differences and the American eel grows faster. So it becomes bigger and stronger earlier, which means that it can leave the current and head to the American continent. But it’s the way back, when the silver eel is crossing the Atlantic from Europe to the Sargasso Sea, we still don’t really know how they find their way back. We know they use their smell. They have an excellent sense of smell. And probably they also use the electromagnetic fields the same way birds do. But it’s a very long and difficult journey.

It’s almost like time and aging are irrelevant for the eel.

What’s so special about the Sargasso Sea?

Yeah, why can they only breed there and nowhere else? Probably it has to do with the temperature, with the pressure and with the salinity of the water. But scientists have tried to recreate the exact same conditions in aquariums or big tanks, but still no one has been able to make eels breed anywhere else other than in the Sargasso Sea.

A Danish scientist, Johannes Schmidt, actually cracked the mystery of where eels come from. What did he do?

That’s one of my favorite stories in the science history of the eel. This was in the beginning of the 20th century, and by that point, scientists knew there were males and females and the eel was breeding like normal fish. But they still didn’t know where it happens. So Johannes Schmidt went out on the ocean with a boat to find the birthplace of the eel. His method was to catch the small larvae and measure them. The place where they were the tiniest, and therefore newly hatched, had to be the birthplace.

Of course, the problem is that this eel larva is very, very small and the Atlantic Ocean is very, very big. So first he sailed from 1904 to 1911 around the shores of Europe and caught a lot of larvae, but they were quite big. So he had to go further out into the ocean, and he found out that the further west he went, they actually became smaller. But World War I broke out, so it was very dangerous to sail around the Atlantic Ocean looking for eel larvae, but he just kept on going. He actually sailed around the Atlantic for 18 years before he found the larvae that must have been newly hatched. So he could say that this place, the Sargasso Sea, was where the eel breeds.

This says something about the human urge to understand nature. What makes a man sail around the Atlantic Ocean for 18 years just to know where the eel is born? There wasn’t any prestige in it. There was no money in it. It was just curiosity. He had to find out. And that’s what makes this scientific history so fascinating. It’s actually more a story about humans.

Steve Paulson is the executive producer of Wisconsin Public Radio’s nationally syndicated show To the Best of Our Knowledge. He’s the author of Atoms and Eden: Conversations on Religion and Science. You can subscribe to TTBOOK’s podcast here.

Lead image: Tatiana Belova / Shutterstock

Prefer to listen?