Ten years ago this fall, Google gave us a glimpse of a new device unlike any it had ever built before—a computer-controlled car. It seemed such a strange thing for an Internet company to spend its time and energy on, a “moonshot” as the company’s engineers called such massive efforts. But with a single blog post, the search giant promised to reinvent our cars, and our communities, too.

It was a big vision for a single invention to carry. And the details were scant. But we quickly filled in the blanks. Software was going to replace our dangerous, congested, sprawling roads with something utterly safe, seamless and organized. Humans would take the back seat in a new network of “ghost roads,” as I call them. Ghost roads didn’t demand a massive mobilization of government. The technology of autonomous driving would roll onto existing highways, invisibly weaving a new transportation system. Only this one would be modeled on the Internet. Computers would outnumber people. Code would call all the shots.

Google almost succeeded. The company’s bold move spurred an arms race, drawing in the rest of Silicon Valley and automakers the world over. Hundreds of billions of dollars flowed into the quest to develop autonomous vehicles (AVs). Still in the lead, Google sister company Waymo now operates a limited self-driving ride-hail service in the Phoenix metro area.

But the future has a way of veering off the road. A generation in, fully automated driving has proven far more challenging than many thought. Some 15 years after university researchers aced the Defense Department’s 2005 Urban Challenge, the first proof-of-concept of autonomous driving in populated areas, Google’s robovans are still mostly confined to the modern subdivisions of the Sun Belt. That’s because scant rainfall and wide, well-marked streets ease the engineering of split-second computer vision systems considerably.

Some experts now predict that we may never achieve the original dream of a reliable fully self-driving car. And even if we do, spreading the technology beyond the Arizona suburbs will require costly retrofits to add navigational hardware to existing roads. This is a non-starter in the post-pandemic age of austerity. Most state and local governments now struggle to merely maintain a much simpler, yet more fundamental technology for orienting both human and computer drivers—the painted markings that guide us along the pavement.

Never has a city flayed itself as deftly and visibly as New York City following the arrival of COVID-19.

Meanwhile, as we’ve obsessed over driverless sedans and SUVs, the magic of autonomous driving has seeped into everything else on wheels. In 2019, University of Michigan urban technology professor Bryan Boyer and his students conducted a census of more than 80 commercially available robots and AVs designed for urban use. Unlike self-driving cars, these machines don’t need AV-only ghost roads to operate. They’re happy to mix it up with people, and defer to human supremacy on sidewalks, in bike lanes, and on streets.

Flipping through the pages of Boyer’s Robot Survey 2019, styled after the old Jane’s guides to military equipment that filled my Cold War youth, the truth is hard to deny. The self-driving car was a red herring. An entire class of AV species, like the mammals once did, will replace the dinosaurs of the automotive age instead.

These strange silicon-powered beasts will arrive just in time. That’s because—as we did when COVID-19 struck—spreading out and shutting down is going to be a tactic we’ll employ over and over again to weather the shocks of the 21st century. How well we put these machines to use to ferry goods and people around in clever new ways, and tend to dull, dirty, and dangerous work of municipal upkeep, will mean the difference between keeping our cities humming along or abandoning them altogether.

Cities have come apart before when confronted with the outbreak of disease. But never has a city flayed itself as deftly and visibly as New York City following the arrival of COVID-19. In March and April alone, an estimated 420,000 people left the Big Apple. The majority fled into the surrounding suburbs. But resort communities and rural towns across a vast hinterland stretching from the Canadian border to the Virginia Tidewater absorbed many emigres. Tens of thousands fled as far as Florida and California.

Even 10 years ago, such a shift would have been unthinkable. But for these self-selected refugees—whiter, richer, and more likely to hold a job suitable for remote work—videoconferencing was a game-changer. Despite the unfairness of this urban exodus, new technology also improved conditions for many of those left behind. An array of services, digitally dispatched with a scale and precision never before seen, stepped in during lockdowns to bring food, medicine, and self-care supplies to the homebound. Delivery volumes doubled week on week, straining but never breaking down.

As the pandemic drama crawls toward denouement in the coming year—whether by deployment of an effective vaccine or a natural decline in transmission—we’re left to wonder what, if anything, of this ad hoc dispersal will persist? Will the digital diaspora put down roots or return to the city? Will stores reopen and if so, will people go out to shop again?

Our ambivalence on these choices is palpable. Nowhere more so than in Silicon Valley, where the world’s most powerful tech firms have given workers a free pass to work from home indefinitely—while also announcing massive plans for new downtown office quarters. Facebook moved early, committing to shift a big portion of its workforce to remote over the coming decade. Yet all along, the company continued to follow through on a pre-pandemic negotiation, signing a deal to lease the landmark Farley Post Office in New York City—a building whose considerable value comes from its proximity to the Pennsylvania Station commuter rail hub, North America’s busiest. Since the start of the pandemic, despite touting work from home arrangements, Amazon, Google, Facebook, and Apple collectively expanded their New York City workforce by over 2,600 employees, more than 10 percent.

The tension of dispersal is grinding us down at home, too, despite high initial enthusiasm. Women have faced an especially turbulent set of new forces—freedom from commutes has given them new choices to manage work and family responsibilities, but the shutdown of schools and child care has further increased the already disproportionate burden of child care and housekeeping they bear. For all of us, the cost of prolonged isolation on productivity, recruitment, career development, creativity, and morale are all still largely unquantified. I suspect most organizations are in bad shape, but unable or unwilling to face it. At some point, they will be pulled apart. The failures could be sudden.

These new neighborhoods don’t feel like the old ones though, as new ways of getting around take hold.

Stuck between a static condition that becomes more permanent with each passing week, and the gravitational field of human social networks slowly reasserting itself—what’s our next move? My hunch is that much like the tech giants, we should embrace the tension, and refashion our cities to be as good at spreading out during future emergencies as they are for crowding together during peacetime.

I call this approach “flexible density,” and this kind of thinking is already visible in our responses to the COVID-19 pandemic. Restaurants shut down dining rooms but shift out into the street, colonizing curbside parking for “streateries” and expanding into the digital realm through multiple delivery platforms. Amazon adds over 1,000 local shipping hubs, slashing delivery times so much that shoppers stop thinking twice about going out to stores themselves. DJs have been locked out of dance clubs but promote live streams to backyard pod parties instead. Everyone discovers that doctor’s visits by screen and prescriptions by mail beats waiting rooms full of sick people. While many of us will go back to the familiar old ways and places after the threat of infection subsides, these new offerings won’t vanish completely when the pandemic does. A lot of them will stick around, and they’ll be there for us again the next time the alarm sounds.

Until now, automation has lurked in the shadows of this transformation. Routing algorithms dispatch drivers. Conveyor droids race across warehouse floors fulfilling our just-clicked desires. Amazon has more than 100,000 conveyors already, toiling away around the clock in more than 100 town-sized shipping sheds. Inside, with humans pushed to the edges, goods-hauling AVs rocket down alleys too narrow for humans at three times the pace of a brisk walk. These robot-dominated interiors are truly inhuman. But extending these ghost roads out into the surrounding world may be the booster shot that’s needed to bolster urban immunity for future crises. Amazon certainly seems to think so. The company bought Silicon Valley AV startup Zoox for $1 billion at the height of this spring’s outbreak.

While automation is one powerful tool for flexible density, paving the way for automation through post-crisis cities can’t be left to companies, however. Flexible density must be designed comprehensively into cities over the years and decades to come. We’ll need buildings that are better suited to adapt when demands for space, security, energy, and ventilation change suddenly. Infrastructure must be pliable enough to extend to dispersed locations on short notice. And a wide array of essential services must be able to find and deliver to constituents and customers wherever they may be. Special attention must be paid to ensure that vulnerable and isolated groups are not left out of the new safety net. All of this will require new investments, new regulations, and new leadership. But as we belatedly start to price in the risks of human settlement in the 21st century, it may prove to be a bargain indeed.

Fast forward to 2040, a world where iron-willed conservation and extreme adaptation go hand-in-hand. The big brush strokes that reimagine our world are painted with laser light, the scanning beams of helpful robots and automated vehicles feeling their way across the urban landscape. In New York City, they now outnumber people. For every one of some 10 million inhabitants, a half-dozen or more artificial ones have taken up residence. Yet while the city is more crowded than ever before, these machines make it possible to spread out even as we pack more tightly together.

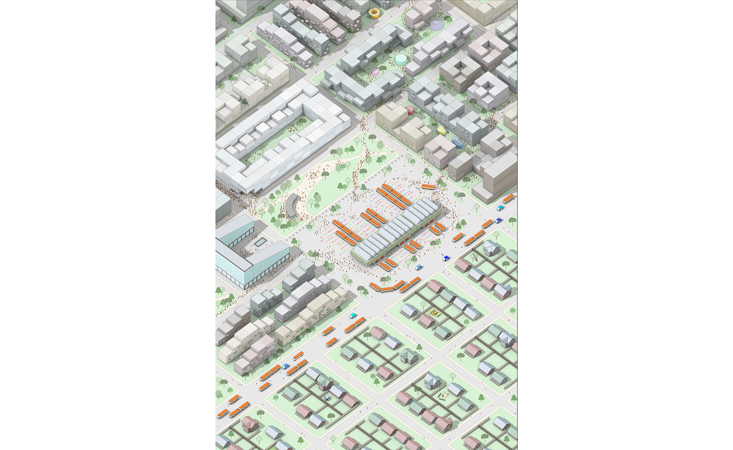

The edges of the old city are where the most profound unraveling is underway. In the far reaches of Brooklyn and Queens a housing boom is in full swing. “Software trains” of automated buses—four and five coaches long, linked together only by a wireless connection—push at high speed along a vast new network of dedicated lanes. These transit-ready ghost roads are only a few feet narrower than the ones we used to lay out for human bus drivers, but with lateral gyrations limited by precise computer control, this belt-tightening makes it easier to squeeze them into a much wider range of city streets. Plowing effortlessly through neighborhoods the subway never reached or fully served, they’re unlocking opportunities to up-zone entire swaths of the city for more apartments.

Even as the risks we face grow, so too do our capabilities. And technology is a tool for boosting those capabilities.

These new neighborhoods don’t feel like the old ones though, as new ways of getting around take hold. Zipping around on “rovers”—a vast category of electric, automated runabouts that includes bikes, scooters, and even wheelchairs—is the way to go now. Summoned with a tap, they’ve crowded out pedal-pushers in the bike lanes, and even displaced cars and trucks from many local streets. Sporting minds of their own, these shared vehicles predictively swarm to where they’re likely to be needed next—outside schools before dismissal, at the stop for an arriving bus, or by the pub at last call. Meanwhile, two-thirds of the stuff residents used to buy in person at local shops now gets delivered by a bewildering array of sidewalk-rolling, stair-climbing, and low-flying bots.

The collective impacts of these changes take some getting used to. Neighborhoods are bigger than ever, as rovers open up a range some five times what people can reach on foot. Snobs call it “microsprawl,” but the people who live there don’t seem to mind the abundance of affordable housing and open space that was always out of their reach in the old subway-centered districts. They adapt to the contradictions. Walking is passé, but cars have vanished, leaving more space for parks. Beloved shops on the high streets are long gone, but so too are most of the big box stores, which are now ball fields (at least the ones that weren’t converted to distribution centers).

Despite all the new machine motion, on the streets people hardly take notice. That’s because the cloud is a clever choreographer, who makes her most important curtain call late at night. Only then do the ghost roads of the city truly come to life. Heavy haulers are sent out, keeping the streets clear of big commercial loads during the day. Municipal robofleets are unleashed to do the dull, dirty, and dangerous work of urban upkeep. Wayward bikes and scooters scurry back to charging docks and disinfection baths. The cute eight-passenger shuttles that have replaced school buses moonlight as parcel vans. Bending time with technology, it turns out, is one of flexible density’s secret weapons for sharing the city without overcrowding.

The hot, close salsa step of big city life isn’t the only dance this city knows, though. Because when a crisis comes—be it pandemic, bombardment, flooding, or worse—it can shift stance to a spread-out, loose-formation waltz with ease.

For starters, this robot-powered metropolis is far more prepared to shelter in place. Municipal bots surge into hotspots—disinfecting, repairing flood barriers, extinguishing fires, or whatever the crisis calls for. And the same automated supply chain that powers e-commerce to our front door in peacetime is re-tasked in an instant to carry relief supplies.

When the situation worsens, though, and it comes time to evacuate, these machines prove their mettle. This city doesn’t panic, it simply spreads out in an orderly fashion. Software trains change their routes to provide instant transit service out of the danger zone. Urban “ushers,” roving street furniture with a mind of its own, close streets and direct evacuations. “Civic caravans,” entire mobile buildings that house essential government services, pick up and crawl under precise, slow-motion computer control to higher ground overnight. Overhead, drones monitor the shifting scene and relay essential communications.

COVID-19 was a gentle warning compared to the stresses that will threaten cities throughout the 21st century. It also exposed striking inequalities in who will bear the brunt of these forces in large cities—migrants, racial, and ethnic minorities, the poor, women, and the elderly were all hit hard. The elite’s preparations to flee are morally inexcusable. But simply hardening cities to ease the pain for those left behind is not enough. We need to shape cities in a way that both eliminates the need for such flight, yet bakes a more controlled, calculated version of it more deeply into the urban DNA.

Seen in this light, flexible density will be a shocking proposition for city builders and their advisors. For centuries, they’ve responded to pandemics by hardwiring social distancing into the urban fabric. After surviving the arrival of bubonic plague in Milan in 1485, Leonardo da Vinci sketched a series of unrealized designs for the city that included broader spaces for circulation. Four hundred years later, the early 20th-century modernists obsessed over windows and plazas in an effort to bring more sunlight and fresh air into buildings and neighborhoods. Because of their rigidity, however, these schemes didn’t weather well. The permanent separation they baked in was too high a cost for city dwellers to bear. Over time, many drifted back to the old packed-in places that pre-dated the new ones. Those classic, tight-knit neighborhoods are still the places people love most. And they are our best models for sustainable, human-centered urban design. But they are not impervious to the shocks ahead.

Flexible density can help us navigate these tensions. It recognizes that dispersal is a strategy for resilience, but need not be permanent, or incongruent with the virtues of compact development. It recognizes the existential nature of the threats that cities face in the 21st century, and that the static way we’ve been thinking about resilience to date may not be enough. Yet it offers hope too. It shows that even as the risks we face grow, so too do our capabilities. And it puts technology in its place, as a tool for boosting those capabilities. Flexible density highlights the potential for advances in automated mobility to unlock new design possibilities for buildings, infrastructure, and services—while not wholeheartedly re-organizing the future around their demands. There is much to be worked out about the details of how flexible density will work in the real world. But it is clear that we can and should challenge ourselves to peek over the horizon and imagine a tomorrow where flexible density is part of how we make ourselves at home on the other side of this very weird and unsettling present.

Dr. Anthony Townsend is Urbanist in Residence at Cornell Tech’s Jacobs Institute, and the author of Ghost Road: Beyond the Driverless Car (2020) and Smart Cities: Big Data, Civic Hackers and the Quest for A New Utopia (2013).

The illustrations that accompany this article were commissioned by the author to imagine concepts in his book, Ghost Road. They were done by the Detroit-based architectural design studio, Dash Marshall (dashmarshall.com).

Lead image: Golden Sikorka / Shutterstock