Like most American high school students, I was required to take Chemistry and English. Chemistry thrilled only by way of the absurdity of allowing kids like me to play with volatile compounds and an open flame. English provided little of that thrill save, perhaps, Holden Caulfield’s excessive swearing or Huckleberry Finn’s audacity in heading down the big river after faking his own death.

I took Mark Twain’s advice to heart and decided I would not let school get in the way of my education. So in lieu of college, I set out to have a look at some of the world beyond the little bit I knew. I traveled some, and along the road someone handed me a book called The Periodic Table by the Italian chemist and writer Primo Levi. I read it. I liked it. I read it again. No, I loved it.

This autobiography, a collection of short stories, explores various slices of a rich life. We read of boyhood pranks, budding romance, friendships fortified through shared adventure, as well as the horrors of Auschwitz. It is not just a rich life, but one well-considered with great sensitivity, smarts, and wit. The final story, “Carbon,” could be the final chapter of anybody’s autobiography—not just a story of death— but a larger perspective of his (our) place in the continuum of the universe. More metamorphosis than death.

Here was an atomic adventure. Here were both Chemistry and Literature on the same pages. Here were molecules and compounds heading down a wild cosmic river like Huck and Jim. In fact, they were Huck. And Jim. And the river. And the raft. The air they breathed, the stars that shined, and even a part of the impulse to pull ashore or keep on going. They were in their yesterday and they will be in their tomorrow.

Levi writes that his story is certainly true, as millions of variations would be equally true. I love the certainty of this truth as well as the blurring of lines, the constant transformations of matter, the endless variations created from a finite set of ingredients and, well, I just love the grand adventure.

The following story, too, is true. I took obsessive care with these drawings to document their subjects, but equally to simply spend time with them, in gratitude for the subject’s unlikely existence at all—and to sear these beautiful and fleeting truths into my brain until it, too, is required for other purposes.

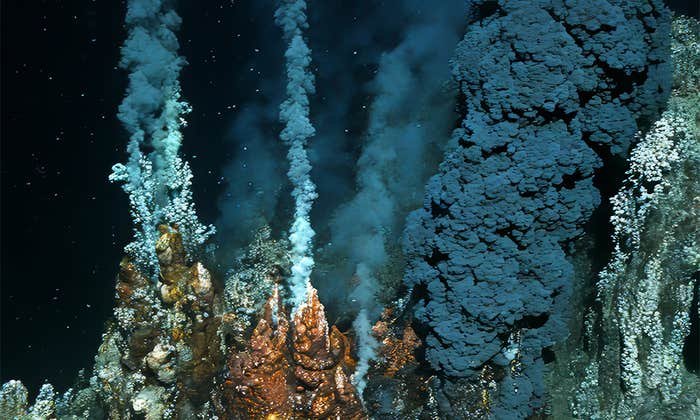

Within one ordinary galaxy, the primordial nebula of one ordinary star provides building materials for its developing satellites. A nearby iron- and silicate-rich terrestrial mass, formed roughly 4.5 billion years ago, has now cooled enough to foster some heavy cargo violently delivered. During the chaos of the Bombardment Epoch, water from asteroids and volatile elements from the protoplanet fall to the gravitational attraction of a young planet Earth.

Life evolves. Replication, selection, and adaptive mutations in response to environmental stimuli produce astounding diversity. The Earth of the Mesozoic Era is hot and wet until its final act—the Late Cretaceous—ushers a colder, dryer climate, continental drift, and falling sea levels. Here is where we find our universal traveler 70 million years ago, still in the form of calcium carbonate in a limestone cliff. Its head is now above water, but it will remain in relative stasis for millions more years, witness to the dinosaurs whose reign is nearly over.

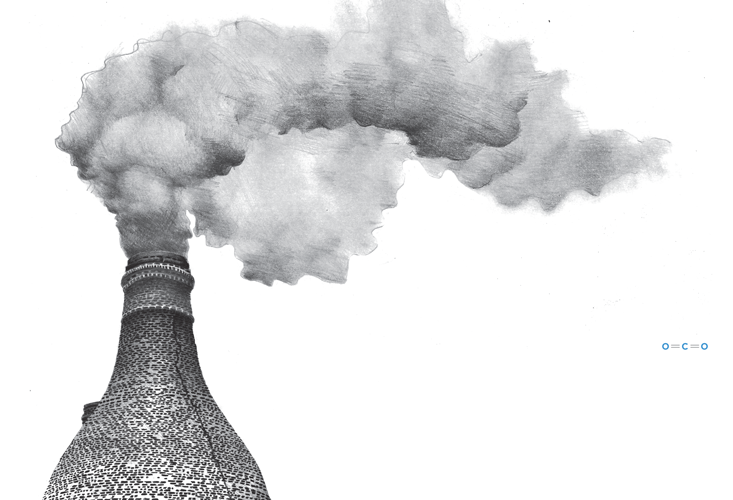

One strain of carbon-based life on Earth—humans and their early ancestors—discovered ways, through their clever use of tools and fire, to manipulate those elements at their disposal, and with increasing sophistication, they did so, changing combinations and states of matter to suit their purpose. Some limestone is cleaved from the cliff with a pickaxe and burned in a kiln. The heat serves to separate our atom from some of its long-standing bonds. Still holding fast to two oxygen atoms, it is now, in the form of carbon dioxide, a gas, free to travel once again.

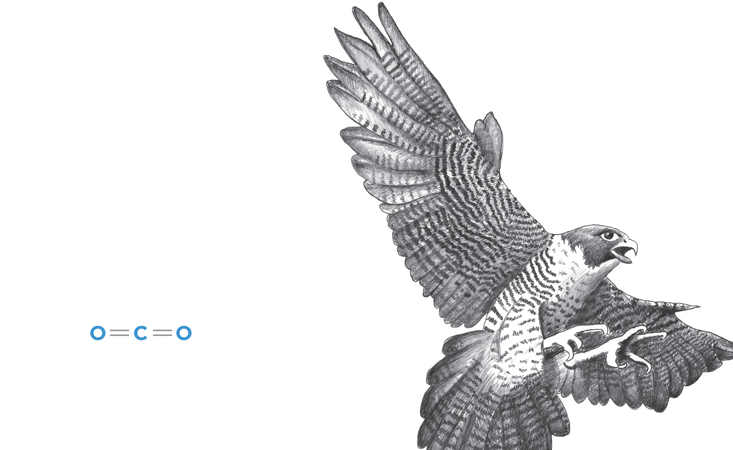

It is breathed in by a Peregrine Falcon—the fastest of Earth’s animals—on a harrowing and precipitous hunting dive, but not assimilated, and later, is expelled.

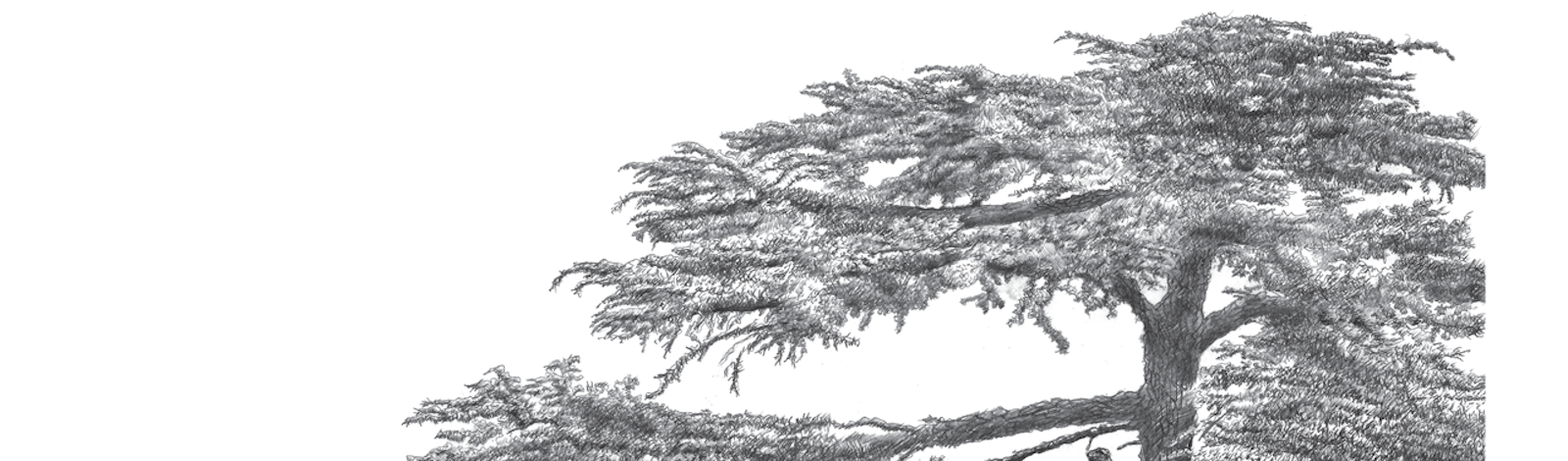

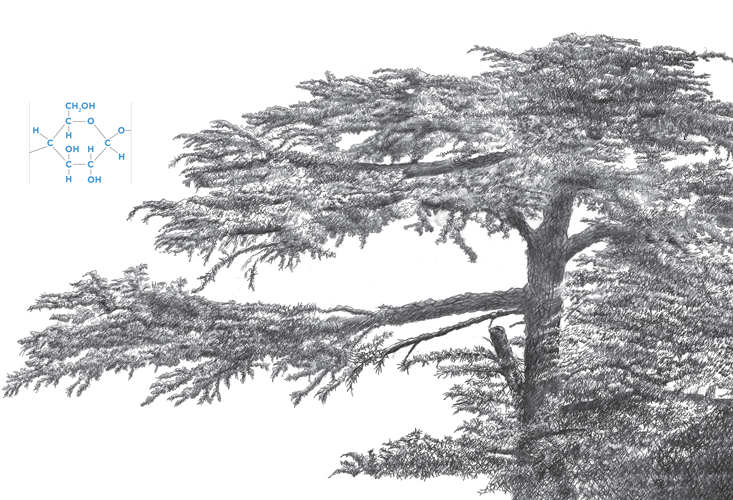

After many more years being carried in currents of water and air, our intrepid atom once again settles, this time on a cedar of Bsharri, Lebanon, and helps to build long molecular chains to form cellulose in this long-lived conifer.

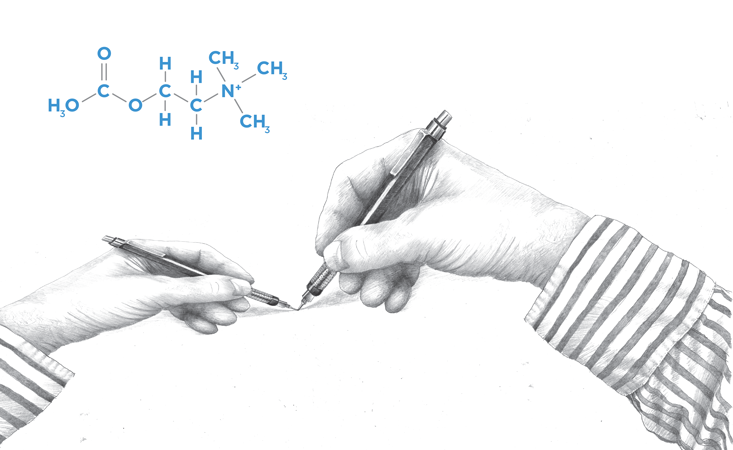

It is in my brain and it is at a nerve terminus that the sugar is eventually synthesized to the hormone acetylcholine, a neurotransmitter. Here it facilitates my neurological function. It serves my consciousness which guides my thoughts. It helps direct my choices toward their necessary motor function. The story is conceived, words are written, images are drawn with pencil (graphite—our old friend carbon!) right to the last mark. Right here.

John Barnett was born in Buffalo, New York. To date, his favorite job was as a shepherd in Cornwall, England. For many years he was a carpenter, even building his own sailboat which, the last he knew, still floats. For the past two decades he’s applied his design and illustration skills to many books. This is the first of his own. The drawings within were done with pencil on paper. He lives in Rhode Island with his wife and three children. More of his work can be seen at www.4eyesdesign.com.

Excerpted from Carbon by John Barnett. Copyright © 2021 by John Barnett. Excerpted by permission of No Starch Press. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.