That natural agent or influence which evokes the functional activity of the organ of sight.” So begins the first definition of light in the Oxford English Dictionary (OED). Additional definitions range from “the inward revelation of Christ” to “the answer to a clue in a crossword puzzle,” yet the seven pages of the OED devoted to defining light scarcely begin to approximate all that light means to us, let alone the significance of light throughout time. In the 13.7 billion years since the universe formed, photons have effected nearly everything, and in the 200,000 years since our species emerged, light has been as central to our existence as water and carbon.

The 20 words defined in this lexicon—from aurora to ziggurat—reflect the ways in which light irradiates the universe and illuminates our perception of the world. Because no single system—scientific, religious, philosophical, or cultural—can possibly encompass every meaning of light, this lexicon is systematically unsystematic, exploring each of these realms through words that serve as synecdoches for ways in which we understand light and its myriad effects.

AURORA

A flaring ring of light illuminating the night sky. Each of Earth’s poles has an aurora, which can occasionally grow large enough to be seen near the equator, inspiring visions of apocalypse. (In the biblical second Book of the Maccabees, the aurora borealis is described as “horsemen charging in midair, clad in garments interwoven with gold.”) For the Inuit, who are more accustomed to it, the aurora is perceived as a football game played by spirits in the heavens. The scientific explanation is no less astounding. Charged particles cast off by the sun are carried by our planet’s magnetic field toward the North and South Poles, colliding with atmospheric gasses and causing them to glow like neon signs.

CAMERA

A device for making photographs. Even before the invention of photography, the camera was a tool for recording observations, preserving the three dimensions of reality on a two-dimensional plane. The camera obscura—a dark room with a small hole that projected outside scenery onto a blank wall—was well known to Aristotle, and aided landscape and anatomy drawing during the Enlightenment. The challenges of working with a camera lucida—a related optical instrument—led William Henry Fox Talbot to co-invent a process he called “photogenic drawing.” Instead of guiding his hand, the light photochemically altered a sheet of paper. The mechanical nature of this process—made progressively more automatic by film and digital photography—gave the camera objective authority over human perception, an irony of historical proportions: The camera obscura was originally considered a model of the eye, showing how little of reality we actually see.

CHLOROPHYLL

The molecule that absorbs sunlight for photosynthesis. Plants and photosynthetic bacteria survive by converting water and carbon dioxide into sugar, and energy is needed to catalyze the reaction. Chlorophyll captures energetic photons. Nevertheless, chlorophyll is not ideal. The two versions of the molecule absorb light most efficiently at the red and blue ends of the visible spectrum. The reflected wavelengths in between make leaves appear green, and mark a missed opportunity. Any sensible engineer would color plants and cyanobacteria black in order to absorb all the sunlight. Natural selection is less fastidious, and chlorophyll is a good enough molecule to feed the whole planet, engineers included.

DEITY

A god or goddess, or the quality of godliness. Throughout the ages, deity has been associated with light. Ancient Egyptians worshipped the sun god Ra. Light was his gaze, and night fell when his eye closed. For Zoroastrians, light was the god Ahura Mazda, creator of the world, and his nemesis was the god of darkness Angra Mainyu, an opposition representing the struggle between good and evil. Judeo-Christian belief is more complicated. Light is God’s first creation in the Book of Genesis, and God is light in the Gospel According to John. But light is also embodied in the fallen angel Lucifer, whose name means bearer of light, and whose fame derives from tempting Eve. Emperors and kings have often crowned themselves with light, aspiring to godliness. Lucifer should serve as fair warning that light can be blinding.

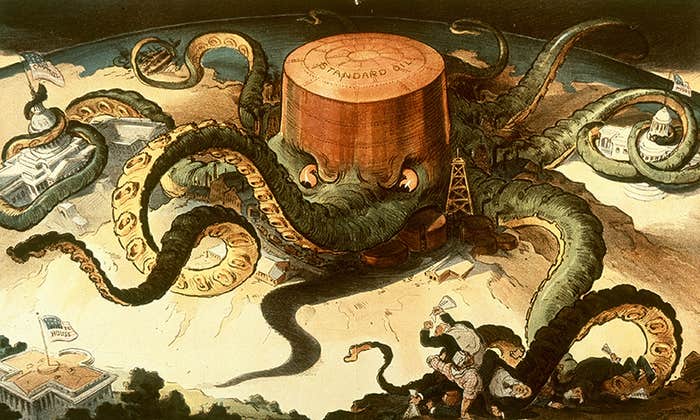

ENLIGHTENMENT

The Age of Reason. The Enlightenment emerged in 18th-century Europe as a counterforce to the despotism of kings and the Catholic Church. Since light was a symbol of deity, and of presumptuous monarchs including Louis XIV, Enlightenment philosophers appropriated the imagery, inverting ancient equations of power. René Descartes followed the “natural light of reason,” and Voltaire cast rational thinking as a torch, held up in stark contrast to the dark superstitions of religion. It was an ingenious feat of propaganda, instantly comprehensible to people who would never read the Cogito or Candide, let alone Isaac Newton’s Opticks—in which Enlightenment rationality was more rationally applied to light.

ETHER

The imaginary medium through which light waves undulate. Ether was a product of Enlightenment anxiety, posited to explain phenomena like gravitation without invoking occult action-at-a-distance. Despite all the varied claims, the explanation of light was ether’s primary attraction. Especially after the 19th-century polymath Thomas Young showed experimental evidence of light waves, scientists felt compelled to describe light in terms akin to acoustics. (If sound waves pass through air, what’s the luminiferous equivalent? There must be something material, as anything immaterial would be spiritual.) To account for light’s vast speed, and also for the lack of ethereal wind as the planet turned, mathematicians calculated the ether must be firmer than steel yet subtler than air. Nobody could find it. Ether was as vaporous as the occult notions it was intended to invalidate.

FILAMENT

The glowing thread inside an incandescent light bulb. More than any other aspect of electric lighting, the discovery of a practical filament eluded inventors, including Thomas Edison. Any carbonized fiber will radiate light when electrified inside an evacuated flask, but the illumination will last mere minutes before the hot filament self-destructs. After announcing that he’d solved the problem, putting gas companies in a panic, Edison experimented with thousands of substances—cardboard, cork, raw silk, human beard—before finding the right combination of qualities in Japanese bamboo. By then, other inventors were finding alternative solutions. (British engineer Joseph Swan used cotton.) But for Edison, the filament was really just the tip of an industry. Light led the way to the electrified city.

FIREFLY

A winged beetle that attracts mates with flashes of light. The light is produced in the insect’s abdomen by the reaction of a chemical called luciferin with oxygen, and the firefly modulates the flashing by controlling the flow of air. Known as “bioluminescence,” the phenomenon is also attractive to humans. In pre-modern Asia, fireflies were kept in cages as living lanterns. (Firefly hunting was a profession in Japan.) Other bioluminescent organisms, from fish to bacteria, have been used for illumination by other cultures, even in mines where using a flame as a light source could be catastrophic. Today the foremost consumers are biologists, who use a firefly enzyme, and the green fluorescent protein from bioluminescent crystal jellyfish, as molecular markers to illuminate medical experiments.

GNOMON

The index on a sundial. Initially clocks were nothing but gnomons: sticks in the ground read by pacing the length of their shadows. With the growth of cities and bureaucracies, sundials became more elaborate and monumental. In the Roman Empire, the grandest used plundered Egyptian obelisks as gnomons, casting shadows over vast temporal grids incised in the ground. By then, water clocks were also common, simulating the sun’s daily progress with the rate water poured from a vessel. It was the beginning of the end for the gnomon and the sun. From pendulums to the oscillations of atoms, clocks became increasingly independent of daylight, eventually more regular than the planetary system they were designed to emulate. Atomic clocks now need to be “corrected” with periodic leap seconds, lest high noon drift into the darkness of night.

HELIOSTAT

A mirror that pivots to reflect a steady beam of sunlight. Before the laser was invented, the sun was the only suitably intense light source for many optical experiments. Clockwork heliostats compensated for the turning of the earth by rotating with the hours. Heliostats do the same today, albeit robotically, to serve a different purpose: Rings of heliostats concentrate the sun’s heat on a central tower to generate megawatts of solar power. These solar thermal plants have endowed heliostats with new experimental value, allowing astronomers to detect even the faintest radiation at night. An eight-acre array at Sandia National Laboratory now moonlights as a gamma ray observatory.

LASER

Acronym for Light Amplification by Stimulated Emission of Radiation. Emitting narrow beams of light that can be tuned to specific frequencies and timed to the attosecond, lasers have transformed fields ranging from global communication—phone and television data are carried in laser light through fiber-optic cables—to internal medicine, underlying modern technology to such an extent that at least half the U.S. gross domestic product now depends on them. But their value was not immediately appreciated. When Hughes Research engineer Theodore Maiman announced the first working prototype in 1960, even his own assistant referred to it as “a solution looking for a problem,” and Hughes declined to develop the technology. One of the first uses was by surgeons blasting tumors. As with the X-ray, the laser first touched our lives through the pragmatism of doctors.

LIGHT YEAR

The distance traveled by light in one year. For most of history, this measure of distance would have been nonsensical, because light was thought to propagate instantaneously. Even those who suspected otherwise, such as Galileo, were unable to prove it because the speed was too great to measure by experiment. Only astronomical observation sufficed—using Earth’s distance from Jupiter in different seasons—and from the 17th to the 20th century the number was gradually refined to 299,792,458 meters per second. That makes one light year approximately 9.5 quadrillion meters, or about a quarter of the distance to Alpha Centauri. But the meter is no longer independent. Since 1983, it’s been defined as the distance traveled by light in 1/299,792,458 of a second.1

METAMATERIAL

An artificial material with a negative refractive index. Light bends as it passes from one natural substrate to another—such as from air to water—and the difference in their refractive index determines how acutely the light is bent. Metamaterials bend light backward, and can even be structured to channel light waves around the periphery of an object, making it appear as if the object weren’t there. In that case, they’re called “invisibility cloaks,” a sci-fi moniker that bends the truth, as most metamaterials are restricted to bending specific wavelengths, often well outside the visible spectrum.

NEON

The tenth element on the periodic table. Neon is an inert gas that glows orange-red when electrically charged. Because minimal heat is emitted, neon lighting is highly efficient, and the ready availability of the gas in the early 20th century—as a waste product in the manufacture of oxygen—led the entrepreneurial engineer Georges Claude to see neon tubing as a replacement for hot filament bulbs. In 1910, he flaunted his invention by illuminating the facade of the Grand Palais in Paris with neon. Given the gaudiness, and the garish hues produced by other inert gases including helium and argon, Claude failed to foment a revolution in domestic lighting, but those same qualities made the tubes ideal for outdoor advertising. In many cities, neon signs still outshine all the stars in the sky.

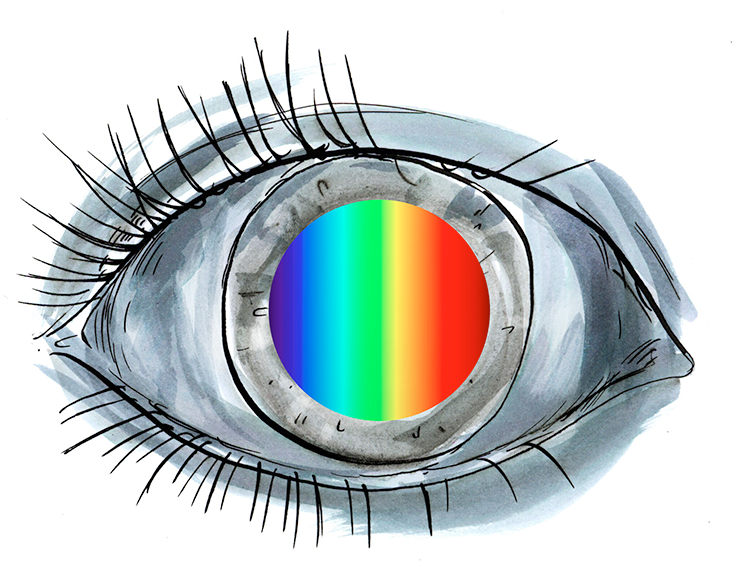

PNEUMA

The mechanism of eyesight as perceived in antiquity. According to Galen, a great doctor of the Roman era, the brain was the seat of the soul, and pneuma were the spirits that traveled from the brain through the eye out into the world and back again: a visual sense of touch stirred by the sunlight. Since Galen’s writings were as good as law to some 50 generations of physicians, his position was not just a philosophical matter. He based his pneuma on dissections of oxen and careful observation of the optic nerve. His description of nerves as tubes through which pneuma passed was mistaken, but he was right to recognize that the senses are communicated through the nervous system.

SPECTRUM

The gamut of electromagnetic radiation including visible light. The colors humans can see, and have observed in rainbows throughout history, are but a small part of the spectrum, and even they are differently perceived according to belief. Newton, for instance, arbitrarily assigned seven color names to the countless hues of sunlight refracted by his prism, imagining an equivalence between the rainbow and the musical scale. A less mystical outlook gave the 19th-century astronomer William Herschel a hint of the spectrum’s true reach when he felt heat at one end of his prism: the invisible warmth of infrared light. As knowledge of the spectrum has expanded, so too has our view of the universe, which now extends to the cosmic microwave background radiation, the afterglow of the Big Bang, and oldest light we can detect.

SUPERNOVA

The explosive demise of a massive star. Exploding with the power of several octillion nuclear warheads, a supernova is bright enough to be plainly seen across the galaxy. (Native American cave paintings record the 1054 B.C. supernova that produced the Crab nebula.) Supernova from as far away as 10 billion light years have been observed by the Hubble Space Telescope, and because all Type Ia supernova have the same brightness, comparing them reveals the expansion of the universe, showing that the expansion is accelerating, spreading matter ever thinner. It’s a lonely cosmic future, but if it weren’t for supernova, we wouldn’t be here to make the observation: Past explosions made the heavier elements that are essential for life, and scattered them throughout the cosmos.

TALLOW

Boiled animal fat used in candles from the Dark Ages through the 19th century. The optimal mix was half sheep and half cow, less smoky and stinky than burning pig’s fat (as long as the wick was trimmed every few minutes). While dimly burning tallow candles provided the only light after sundown in working-class homes, the aristocracy splurged on spermaceti, rendered from the head matter of sperm whales. Since the spermaceti flame was spectacularly bright, and most scientists were aristocratic, candlepower was defined as the light produced by a two-ounce spermaceti candle burning at a rate of 120 grains per hour, a standard measurement that has outlasted both whaling and candles.

X-RAY

High-energy radiation capable of penetrating opaque solids. Wilhelm Conrad Röntgen, a German physicist, discovered X-rays accidentally on Nov. 8, 1895, when he noticed that discharging high-voltage electricity in an evacuated glass tube caused a chemically treated screen to glow. Even stranger, when he put his wife’s hand between the tube and a photographic plate, he got an image of her bones. His X-rays were published in newspapers across Europe. By January 1896, doctors were using his method to diagnose broken limbs. But mainstream adoption preceded comprehension, as evinced by many inventors’ efforts to photograph thoughts. Concurrently there was a wave of paranoia about the end of privacy. Even if X-rays couldn’t penetrate an individual mind, they brought to light the collective hopes and anxieties of society.

ZIGGURAT

A stepped pyramid to stand on while studying the sun and stars. Ziggurats were built by the Chaldeans in Babylon during the 6th century B.C., and painted the colors of the rainbow. Though the Chaldeans were said to be the first astronomers—able to predict the length of days and dates of eclipses—their scientific achievements were motivated by astrology, upon which important decisions depended. There was sound logic to this: Heeding the sun improved agriculture, so why not also marriage and warfare? And in any case, the sun was a deity. Atop the grandest ziggurat of all, some 400 feet tall, was a shrine with a bed where a nubile girl slept every night to await the sun’s lusty arrival.

Writer and artist Jonathon Keats is the author of six books including the story collection The Book of the Unknown, winner of the American Library Association’s 2010 Sophie Brody Medal, and Forged: Why Fakes are the Great Art of Our Age. He is currently writing a book about Buckminster Fuller.