Science may happen in laboratories, but that does not isolate it from the rest of human society. Scientists are just as likely as any of us to become concerned about what is happening in the wider world, and to feel the urge to express their views. For some of them, though, there is a residual unease about doing this that is not felt by the rest of us; because scientists work in a highly specialized arena, sometimes there is a reluctance to speak out in areas beyond their narrow expertise. Others overcome their diffidence, however, and bring their scientific rigor to bear in arguing a case all the more forcefully.

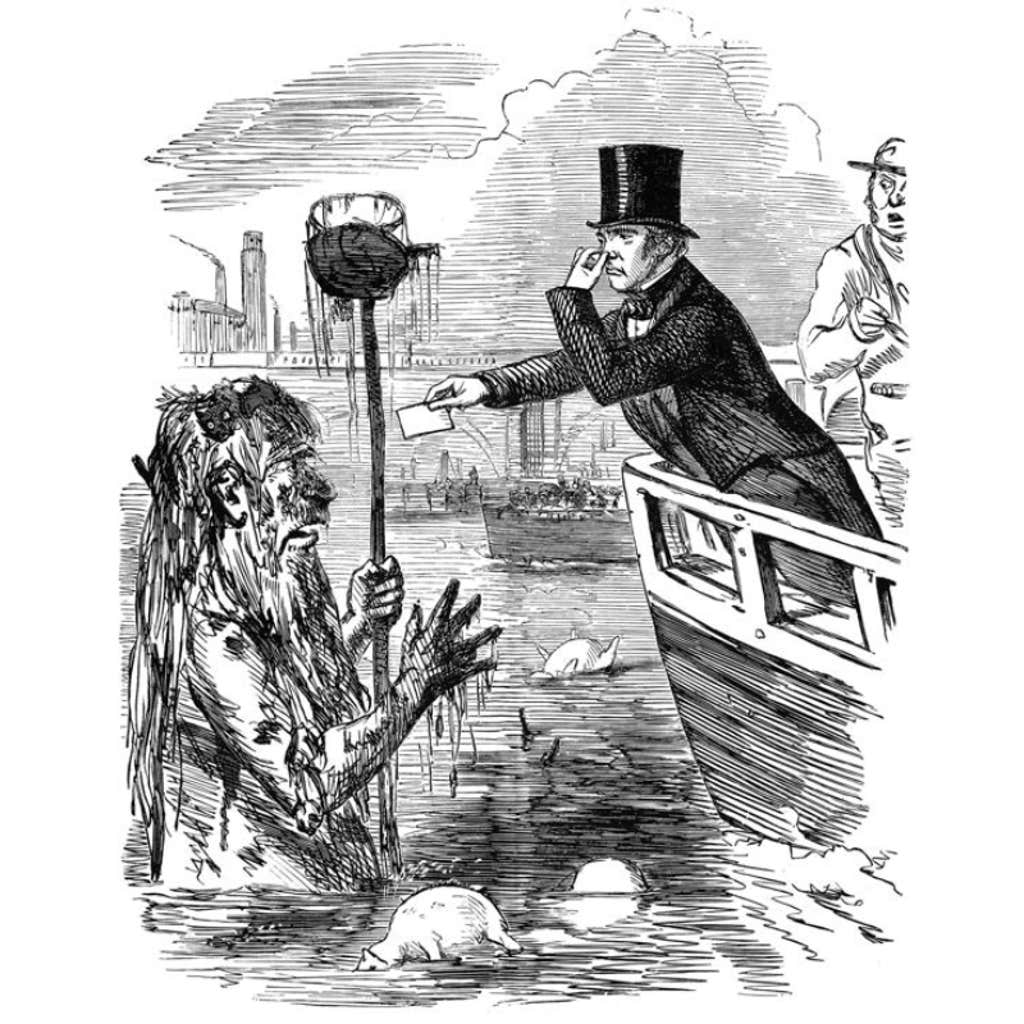

Michael Faraday is one of the latter kind, when he writes to The Times to protest about the level of pollution in the River Thames. He makes his point by describing an experiment he has carried out, in the hope that the authority of the scientific method will prove persuasive. And he emphasizes that there is “nothing figurative” in the language he uses—in other words, his description should be taken as scientifically accurate.

Surely the river ought not to be allowed to become a fermenting sewer.

The River Thames has been an important source of life for the South of England, even long before the sprawling city of London sprang up upon its marshy banks. Not only has it provided food and water for centuries of the area’s inhabitants, but it has also served to facilitate trade and power industries. By the Victorian era, however, the incessant dumping of human and industrial waste into the very same life-giving water had reduced the breadbasket of the Thames in London to an open sewer, resulting in a stench so great it nauseated even those with the most limited sense of smell.

So intolerable was the smell emanating from the Thames that it was not until the physician John Snow in the mid-19th century traced the source of a particularly deadly outbreak of cholera in London’s Soho neighborhood to a single water pump that people began to believe the disease was waterborne and not transferred by the river’s “bad air.” Horrified members of the public regularly wrote letters of complaint to newspaper editors and the government.

By far the most famous of these letters is that sent by Faraday. Renowned as one of the most influential scientists of his age, notably for his work in electromagnetism and electrochemistry, Faraday was also a man dedicated to public service. He was regularly involved with the issues affecting society, from investigating coal mine explosions to overseeing the construction of essential lighthouses.

In his 1855 letter to The Times, Faraday reported the damning findings of a recent experiment he had conducted to measure the extent of the river’s pollution. Repulsed by the results, he made a public appeal for the authorities responsible for the city’s health and sanitation to take action.

These pleas, unfortunately, fell on deaf ears. It would not be until the “Great Stink” of 1858, when an intense heatwave accentuated the smell of the river tenfold, that the Members of Parliament at Westminster decided to act. Only after attempts to abate the smell by dumping chloride of lime and carbolic acid at the mouths of sewers flowing into the Thames had failed did they finally decide to back the civil engineer Joseph Bazalgette’s model for a new sewer system. This eased the pressures on London’s sewers and moved waste to points of the river beyond the bounds of the city. Impressively, much of his structure is in excellent working order and still in use today.

From Michael Faraday to the Editor of The Times, July, 7, 1855

Sir,— I traversed this day by steamboat the space between London and Hungerford Bridges, between half-past one and two o’clock. It was low water, and I think the tide must have been near the turn. The appearance and smell of the water forced themselves at once on my attention. The whole of the river was an opaque pale brown fluid. In order to test the degree of opacity, I tore up some white cards into pieces, and then moistened them, so as to make them sink easily below the surface, and then dropped some of these pieces into the water at every pier the boat came to. Before they had sunk an inch below the surface they were undistinguishable, though the sun shone brightly at the time, and when the pieces fell edgeways the lower part was hidden from sight before the upper part was under water.

This happened at St. Paul’s Wharf, Blackfriars Bridge, Temple Wharf, Southwark Bridge and Hungerford, and I have no doubt would have occurred further up and down the river. Near the bridges the feculence rolled up in clouds so dense that they were visible at the surface even in water of this kind.

The smell was very bad, and common to the whole of the water. It was the same as that which now comes up from the gully holes in the streets. The whole river was for the time a real sewer. Having just returned from the country air, I was perhaps more affected by it than others; but I do not think that I could have gone on to Lambeth or Chelsea, and I was glad to enter the streets for an atmosphere which, except near the sink-holes, I found much sweeter than on the river.

I have thought it a duty to record these facts, that they may be brought to the attention of those who exercise power, or have responsibility in relation to the condition of our river. There is nothing figurative in the words I have employed, or any approach to exaggeration. They are the simple truth.

If there be sufficient authority to remove a putrescent pond from the neighbourhood of a few simple dwellings, surely the river which flows for so many miles through London ought not to be allowed to become a fermenting sewer. The condition in which I saw the Thames may perhaps be considered as exceptional, but it ought to be an impossible state; instead of which, I fear it is rapidly becoming the general condition. If we neglect this subject, we cannot expect to do so with impunity; nor ought we to be surprised if, ere many years are over, a season give us sad proof of the folly of our carelessness.

I am, Sir, your obedient servant,

M. Faraday.

Excerpted from Letters for the Ages: Great Scientists: Private Letters from the Greatest Minds in Science, reprinted with permission of the author, courtesy of Bloomsbury Continuum, an imprint of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc. Copyright © 2024

Lead cartoon: From Punch magazine; Faraday Giving His Card to Father Thames; And we hope the Dirty Fellow will consult the learned Professor by John Leech.