Ascension Island is a volcanic land mass in the Atlantic Ocean. Located midway between Africa and South America, its edge stitched with sandy beaches, it’s a popular nesting site for green turtles, who haul themselves up by the tens of thousands each year to dig holes and lay their eggs.

Because the temperature of the sand incubating a sea turtle’s egg will determine the hatchling’s sex, exactly where on the island a given egg ends up has intergenerational repercussions. Eggs laid on Ascension’s white sand beaches may grow up male or female, depending on air temperature, rainfall, and other variables. But those laid on the island’s stretch of black sand beach—which soaks up the tropical sun’s heat and holds it—will always hatch female. Those females will grow up, mate, and return to the same beach to nest—and their offspring will be female, too. Historic temperature reconstructions suggest that “in the last 150 years, there wouldn’t have been a single male turtle produced” on the black beach, says Graeme C. Hays, a sea turtle biologist at Deakin University in Geelong, Australia. “It was just so hot.”

Because Ascension has so many beaches, things there balance out: Females born in the black sand can meet, and mate with, males from nearby shores. Elsewhere, though, imbalanced sex ratios, combined with other threats, may extinguish turtle populations. As the world warms, this possibility looms over more nesting sites. Eventually, it could threaten entire species. Predicting when and where such dire scenarios might come to pass, and how people might try to intervene, is difficult—but a better understanding might allow us to help these animals, who’ve swum Earth’s waters for more than 100 million years, survive our fast-warming age.

Knowing that cooler temperatures lead to male hatchlings and warmer temperatures foster females seems like it would make predicting sea turtle sex ratios straightforward, but it doesn’t. Although researchers first discovered temperature-dependent sex determination in reptiles in 1966, and began investigating it in turtles soon after, there are still many things we don’t understand about how it works.

For instance, sex determination occurs during a certain window of embryo development—but scientists don’t know exactly when that crucial phase begins, or how long it lasts. Researchers have narrowed it down to “somewhere in the middle third” of the incubation period, says Hays. But that isn’t as specific as he and others would like.

They know approximately what incubation temperature will trigger female development—about 84 degrees Fahrenheit, or 29 degrees Celsius. But researchers haven’t pinpointed the precise temperature at which the switch flips. “If your nest’s at 28 degrees Celsius, you’re bombproof to say that 100 percent males are being produced,” Hays says. “And equally, if your nest’s at 31 degrees Celsius, you’re bombproof to say it’s 100 percent females being produced.” The middle temperatures are more mysterious.

In the past, researchers narrowed down the range by incubating eggs at specific temperatures in labs, and cataloging how many males and females hatched. But because young turtles don’t have external sex characteristics, the only way to understand the results of these tests is to kill the hatchlings and examine their gonads under microscopes. As a result, large experiments that might lead to a finer-grained understanding of the temperature pivot point—or how that point may vary between species, or even within populations—are “generally not done now,” Hays says. A search is currently on for a hatchling sexing tool that works on-site with a small blood sample. “That’s the dream,” says Hays.

Cooler temperatures lead to male hatchlings, while warmer ones foster females.

In the early 2000s, the field was revolutionized by another seemingly simple tool, he says: Small, reliable temperature loggers. These devices began proliferating after the European Union passed laws around chilled food transportation, and can now easily be deployed on beaches around the world to collect detailed—and accurately timed—temperature fluctuations.

Scientists also don’t yet know what ratio of females to males spells trouble for turtles. A population with a strong female skew can actually do well, says Hays, because one male can mate with many females. “Eighty percent female, 85 percent, 90—those are probably all pretty good,” he says. But it can go too far: At a certain point, the sex ratio will become so lopsided that females can’t find mates. “When that point occurs—that’s the unknown at the moment,” Hays says. “Is it when it’s 98 percent [females]? Ninety-nine?”

Turtles’ long lifespans make everything even trickier. Green turtles take at least 20 years, and sometimes up to 50 years, to reach sexual maturity. That means the sex ratios of populations swimming today were forged in sand a quarter- or even a half-century ago. “By the time you don’t see any males out there, it’s too late,” Hays says. “The problem happened 25 years previously.”

Predicting when and where such dire scenarios might come to pass is difficult. For a study published in Global Change Biology, Hays and two colleagues—Jacques-Olivier Laloë, also from Deakin University, and the late Gail Schofield, of Queen Mary University in London—estimated past, present, and future male-female breakdowns for dozens of nesting sites across the world. They hope to shed some light on the many remaining sea turtle sex mysteries, and to pinpoint sites that may be creeping toward catastrophe and where people might try to intervene.

The researchers sifted through the scientific literature to gather temperature and sex ratio data for 64 nesting sites across the world, housing all seven sea turtle species and covering the years between 1960 and 2022. They found that nesting site temperatures rose by an average of 0.45 degrees Celsius across those decades. Some sites warmed more than others—but highly female-skewed sex ratios did not always correlate with extreme temperature changes, suggesting that some sites were hatching mostly females even before recent warming occurred.

The sex ratios of populations swimming today were forged in sand a quarter-century ago.

This brings up another sea turtle sex mystery: whether skewing toward females at higher temperatures is actually a helpful adaptation, rather than evolutionary happenstance. In a 2020 BioEssays paper, biologists Pilar Santidrián Tomillo and James R. Spotila propose that sea turtles may have evolved to hatch more females than males, especially in dangerously warm conditions.

“We have been trained to think that a 50 percent sex ratio is what is needed,” says Santidrián Tomillo. “That’s not the case for all populations.” Sea turtle females spend so much time nesting and energy laying eggs that they’re frequently out of the mating pool, she says. A female skew actually balances things out, yielding a more even ratio of available females to males.

But why is this achieved through temperature-dependent sex determination, rather than with sex chromosomes or via a different environmental trigger? Santidrián Tomillo and Spotila propose that it’s a kind of feedback mechanism, providing a response to another consequence of high temperatures: increased hatchling mortality. While warm temperatures produce females, too-hot sand actually kills the eggs in the nest, lowering the next generation’s overall survival rate.

“Because mortality is increased at high temperatures, it seems a good idea to produce females at these temperatures,” Santidrián Tomillo says. “When things are bad, if you make more females, eventually you will make more turtles,” which can make up for population declines. With this in mind, temperature-dependent sex determination “may not be an imperfect system that feminizes populations,” she and Spotila write, “but rather a magnificent solution to overcome a climate-related threat.”

But this, too, is workable only up to a point. Hays and his team made a shortlist of nesting sites that he characterizes as “ticking time bombs:” those that skew heavily female already, and are experiencing rapid warming. This category contains a range of sites, including St. Eustatius Island in the Dutch Caribbean (where 91.5 percent of sea turtles are estimated to be female), Wan-An Island in Taiwan (93 percent), and Raine Island in Australia (more than 99 percent).

Turtle populations in these places are in danger—not just of reaching a sex-ratio tipping point, but also of losing offspring entirely as temperatures rise. While sea turtles can shift their behavior in response to environmental changes—laying their eggs earlier in the year or finding cooler nesting spots—warming in these places is happening too fast for them to keep up. Meanwhile, turtle populations across the world suffer even more immediate threats, including indiscriminate fishing equipment and loss of nesting habitat. Those facing these compounding stressors “will need management intervention,” says Hays.

This is where temperature-dependent sex determination could be especially useful: If you’re the one determining the temperature, you also determine the sex ratios. In the right time window, “a day or two of heavy rain” might bring a hot beach down to male-producing temperatures, says Hays. A human-run sprinkler system could do the same.

“Around the world, people are getting to the point now where they’re starting to think about, when and how do we intervene?” says Hays. More detailed knowledge—about temperature tipping points and ideal ratios, from portable loggers and baby turtle blood tests, gleaned by looking at the past and projecting into the future—could make this easier to determine. “People shouldn’t need to guess going forward,” he says. “They should have hard data.” ![]()

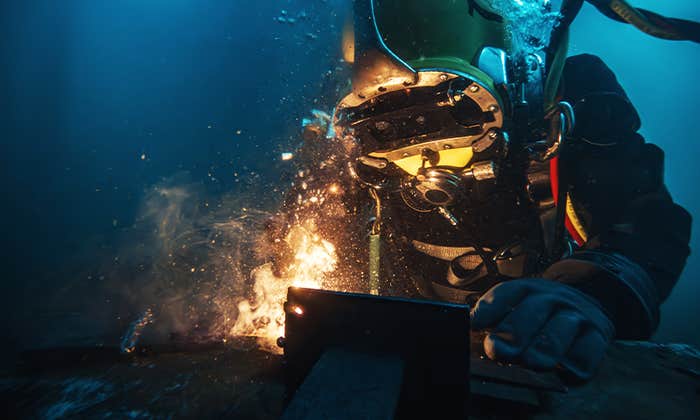

Lead image: David Carbo / Shutterstock