One moment a flounder lies hidden in the sandy bottom of the ocean, the next it vanishes in the bloody frenzy of a shark’s dinner. The shark didn’t see or hear the fish; it pinpointed it from the infinitesimal electrical signals of the flounder’s beating heart.

This seeming superpower is called electroreception. It allows sharks to locate electric fields from a few feet away using sensory organs in their skin.

The flounder’s signal sparks a “little jolt in the shark’s brain,” says Chris Braun, who studies animal sensory systems at Hunter College in New York. To appreciate how the shark zeroes in on the flounder, says Duncan Leitch, who researches sensory adaptations in vertebrates at the University of California, Los Angeles, imagine “navigating toward a hot lightbulb with your eyes closed and hand outstretched.”

Electroreception is an extra sense, not a substitute. Sharks hear well, have good vision, and can smell blood in the water from a quarter mile away. But within a few feet, electroreception is the go-to sense. You don’t want to challenge a shark to a game of hide-and-seek.

Paddlefish electroreception is so sensitive it can detect plankton.

When researchers placed an electrode generating electricity near a dead fish, they discovered that sharks tried to eat the electrode. Biting where the electricity is also likely explains sharks chewing underwater cables, including transoceanic internet cables that provide global connectivity.

Electroreception exists in fresh- and saltwater fish, some amphibians, such as the axolotl, and even a few mammals, such as the platypus, which has electroreceptors on its bill, and the echidna, which sticks its electroreceptive nose into water or damp soil. The Guiana dolphin has electroreceptors on its snout. This extra sense is all about evolutionary creativity and thrift.

In 1678, while dissecting a torpedo ray, the Italian physician and ichthyologist Stefano Lorenzini discovered the sensory organs in the skin that detect electroreception, which he described as gel-filled elongated pores, and which are now known as ampullae of Lorenzini or ampullary receptors. But Lorenzini didn’t understand what these ampullae were for. Since then, scholars have been piecing together how the sensors evolved and how animals use them.

Insights into electroreception grew out of research into another sensory system in aquatic animals: “lateral lines.” These receptors in the skin along the sides of fish or amphibians contain motion-sensing hair cells, named for the hair-like protrusions on the external surface of the cell, that fish use to sense movement, vibrations, and pressure changes in water. These hair cells are similar to ones in our inner ear, and they function similarly: Just as a sound wave pushes the endolymph fluid within our inner ear to bend or move the hair cells, so does water move the hair cells in the lateral lines of a fish.

The lateral line system extends down the body of the fish, but electroreceptors are primarily on the head, often concentrated near the mouth. From the surface, they look like pits or pores, but they extend as deep as several inches into the body of a fish, fanning out from the snout like tendrils of cooked spaghetti. The canal walls secrete a jelly that conducts electricity down to the hair cell similar to how silicon conducts electricity in computer chips. This is how the shark senses the flounder’s heartbeat beneath the sand.

The similarities between the lateral line system and electroreceptors led scientists to the hypothesis that the latter evolved out of the former. Based on similarities in which cranial nerves connect to the lateral line and electroreceptors, it is likely that electroreception first evolved in some common fish ancestor, and later, some of the most common fish—including catfish, tuna, and salmon—lost it.

You don’t want to challenge a shark to a game of hide-and-seek.

In animals that possess it, weak electroreception has evolved to be selective. Weak electrical fields don’t travel very far in air, but aquatic environments are full of them. Even animals with electroreception don’t perceive all electrical fields in the water. That would be noisy and overwhelming, Leitch explains, and so the receptors are tailored to the low frequencies that are most relevant to the given species, such as the frequencies their prey emit.

Remarkably, electroreception has re-evolved at least twice in fish whose ancestors had previously had it and lost it. “Sensory systems take a lot of energy,” Leitch says. “So, if the animal isn’t getting an advantage, and it’s using some other senses like smell or vision more, then there would be less pressure to maintain electroreception and eventually it would become nonfunctional.” At some point, knifefish and catfish lost their electroreception, then redeveloped it.

To shed light on this extrasensory system, Clare Baker, a professor in Cambridge University’s Department of Physiology, Development, and Neuroscience, studies embryos of electroreceptive fish. In 2017, Baker focused on paddlefish, who possess electroreception so sensitive that they detect electric fields generated by the tiny zooplankton on which they feed.

Electroreception in paddlefish arises out of a patch of thickened skin on an embryo’s head called placodes, a layer of cells that contribute to the development of senses. Baker and colleagues show that mammalian inner ear hair cells (critical to our own hearing and balance) develop from the same type of placodes. “As-yet unidentified genes presumably help orchestrate whether a hair cell or electroreceptor develops,” Baker says.

Electroreception offers a fresh insight into how evolution operates from “conserved mechanisms,” scientists say, related genetic processes in animals from paddlefish to platypuses to us. But to the sharks, electroreception is just better odds of securing dinner. ![]()

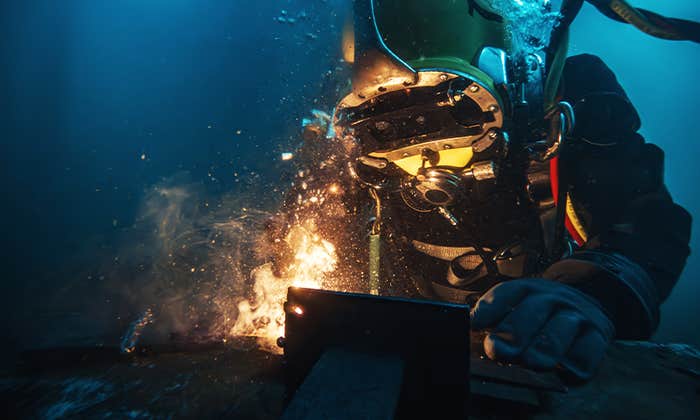

Lead image: An Vin / Shutterstock