I want to tell you about the most absolutely wild book I have ever read about the human body and mind. I discovered it from an author’s offhand reference in The New York Times Book Review and bought it from an online antiquarian bookstore.

But I’m not sure where to start because if science writing is a round hole, this book is a giant square peg. The best I can say is The Body Has a Head by doctor and teacher Gustav Eckstein, published in 1969, reads like Gray’s Anatomy written by James Joyce.

Descriptions of biological mechanisms start out straightforwardly enough, explaining, say, the stomach is J-shaped. But the descriptions soon take flight on metaphoric reveries that compare what’s going on inside our bodies to the carnival of life outside them. Talk about interconnection. Of science bridging art. Let’s have some examples.

• While the attacking molecules and the food molecules are engaging each other in chemical combat, muscles of the stomach wall are acting on the softening lunch. A nagging. A maceration. A trituration. A pushing forward. A steady pressing on the late filet mignon or goose like the pressing on a toothpaste tube. Nothing that once gets into the digestive tube is allowed to loiter.

• Why do we have pain? Why do we have this sense forever waiting? Someone, too discriminating, called it music. Doloroso. The whole orchestra, all the violins especially, first, second, viola, cello, bass, now and then a complaint from the oboe, a crash from the brass, a rumble from the drums. Why? The creature must be forewarned. Pain is preventing destruction going too far by making a quick announcement whenever anything has begun threatening the flesh, and something almost always is.

• A road map is in the mind of every neurologist or neurosurgeon. He sees the events. Urine enters the tank, rises in the tank, a report goes to the owner, who reaches a decision, telegraphs initial orders from mind to brain, that frees the spinal-cord center of its duty to stem the tide, and bladder wall and its double-valve outlet go into action. The bladder contracts, the internal outlet valve releases, the urine keeps pressing, the external relaxes, the floodgates open, and all is well. Assistance is given by the abdomen, whose muscles are holding firm while everything below is relaxing. “A machine made by the hand of God.” Relaxing could have been changed to contracting if the gentleman had, for instance, decided to finish his crossword puzzle.

Trust me, these are just a few of the flares in this volcano of exposition. 784 pages! A reviewer in the Journal of the American Medical Association in 1970 tutted that the book “is narrated in what I call a floating hyperbolic style, undisciplined and interminable, a sort of flamboyant free association.” As if that were a bad thing!

You’re fine not reading the book from the first page to last. The chapters are short with a lot of subsections, so you can sneak in anywhere. Along its serpentine paths you’ll encounter Hippocrates, Descartes, Shakespeare, Thomas De Quincey, Beethoven, Louis Pasteur, Einstein, Pavlov, Poe, Nietzsche, Phineas Gage, and a supporting cast of surgeons from the 17th, 18th, and 19th centuries, portrayed through their grisly tales of experimentation.

Of course, there’s a big hole here. A fault in Eckstein’s stars. Badly missing from his opus are women in philosophy, science, medicine, and art. (Georgia O’Keeffe merits a few lines to illustrate subjective perception caused by the interplay of eye angles and vision neurons.) The Body Has a Head is also autobiographical, I suspect, as the anatomy lessons are often fleshed out by scenes from a hospital, where Eckstein coolly comments on all manner of macabre scenes, gossiping like a rascal about other doctors, nurses, and patients.

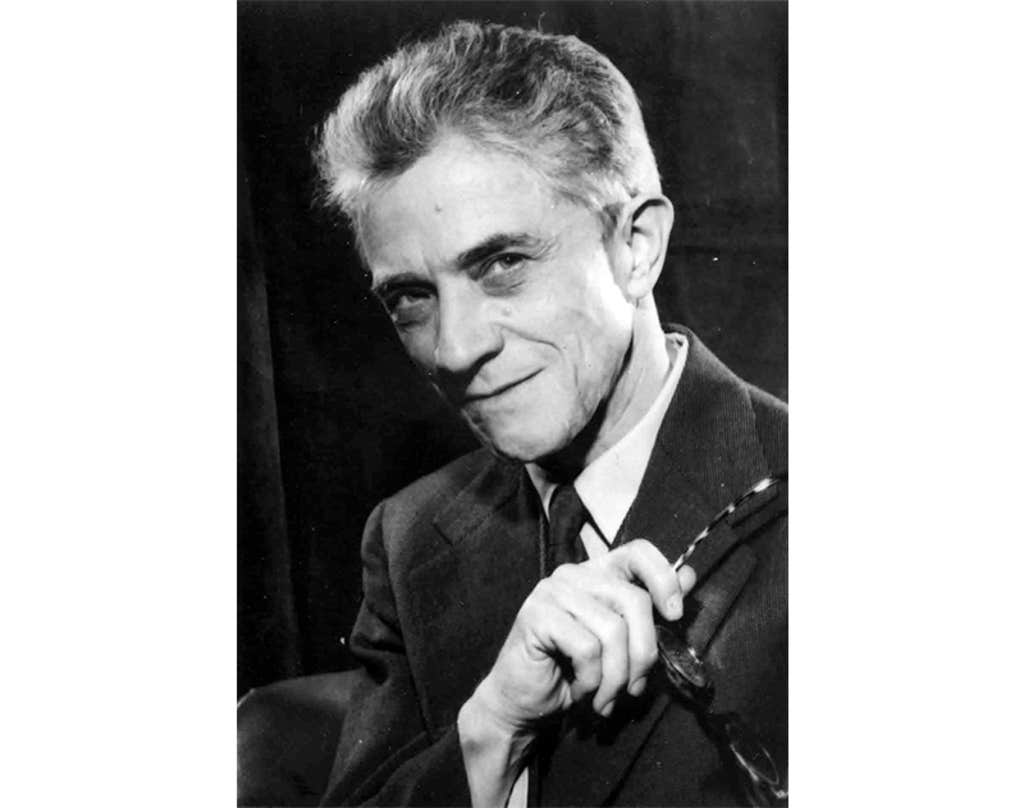

Who was Gustav Eckstein? He was a dentist from 1911 to 1918, then earned an M.D., and then settled into a long run as a professor of physiology at the University of Cincinnati Medical School. He lived nearby in a resident hotel for 40 years. He was briefly married when he was young. He died at age 90 in 1981. His friends, students, and patients knew him as Dr. Gus.

“Dr. Gus was a slight man with a shock of unruly hair atop a too large head,” wrote his friend and fellow doctor, the late Stanley Block. “He was curious about everything. And everything aroused his curiosity.”

Before The Body Has a Head, Eckstein had written eight books and one play, about an Irish woman in America troubled by her overweening father; it flopped on Broadway. One of the books was about canaries and another, Everyday Miracle, about the animals around him, notably Willy the cat, who every Monday night at 7:45 crossed town to sit in a window and watch a bingo game. How did Eckstein know? He followed him. Eckstein loved his pet macaw and on Saturday nights took him to the symphony, hidden under his coat.

Eckstein installed a screen door inside his university lab door. That was to make sure the flock of canaries flying freely in his lab didn’t get out. Nor the mice who made the lab floor their playground. Visitors who dropped by and dodged the birds and mice would invariably find Eckstein at his typewriter, pecking away, wearing a straw hat to keep the bird poop—notable on countertops, books, and chairs—off his hair.

I can’t imagine a more perfect scene to capture the author behind The Body Has a Head. There he was, typing away in a fury, canaries above, mice below, grinning with a mordant glee, pouring out everything from his capacious brain, making literature like none other out of science and medicine. ![]()

Lead image: lynea / Shutterstock