For centuries, an odd form of iconography has maintained a stranglehold over the globe: the octopus map. Political cartoonists and mapmakers have long used the creature to illustrate a wide variety of forces threatening to throttle their foes: from empires, religious groups, and ideologies to financial systems—even abstract concepts such as the great unknown.

Take famed British satirist Fred W. Rose’s 1877 map, which depicted Russia as an octopus slithering its many arms around the globe. It was published shortly after Russia attacked the Ottoman Empire. Map-dwelling military octopuses multiplied through the 20th century: They were commonly drawn during both World Wars, for instance, by satirists and cartoonists on both sides of these conflicts. Today, subtle echoes of these forms persist in data visualizations, which have become popular forms of communication both in the media and for fringe political groups. Many of these data maps feature radiating series of outstretched lines and arrows wrapping like tentacles around continents, including depictions of immigration.

Michael Correll, a data visualization researcher, and his colleagues at Northeastern University wondered if these data-driven images were making subconscious appeals to audiences’ emotions, so they set out to assess how octopus iconography works on the mind. They approached the question from two different angles: analysis of historical examples and an empirical study of human participant responses. What they found is that even subtle octopus imagery in maps can inspire conspiratorial thinking in viewers. They published their results this spring.

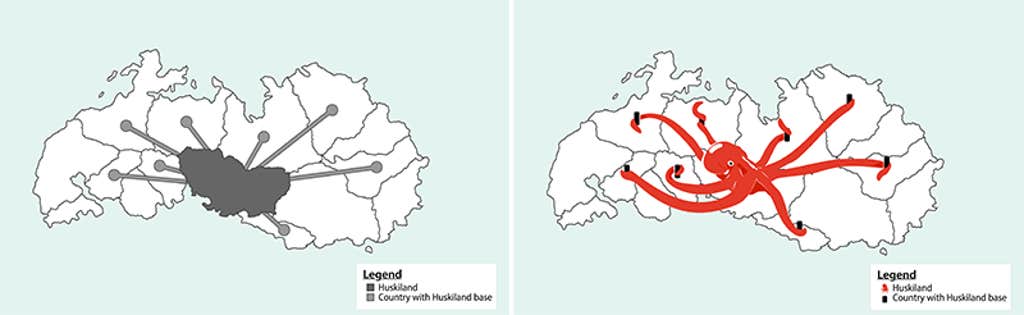

For the empirical arm of the study, they designed a series of maps that illustrated connections between a fictitious country called Huskiland and its military bases in neighboring nations, meant to appear in an international newspaper. These maps ranged from overtly octopus-like to more subtly octopus-like, with lines between nations ending in circular nodes.

The team surveyed 256 participants, asking them to rate on a scale of one to seven how much they agreed with statements such as, “Huskiland is a central military power in the region” and “Huskiland uses these bases to exert military or political control over its neighbors.” These statements aligned with the common elements within octopus maps that the paper authors identified in historical examples, such as “Tentacularity,” “Reach,” and “Threat.”

Ultimately, their survey results indicated that even the more subtle maps “could still engender negative sentiments and attributions of ill-intent” on a similar scale to those with more overt octopus imagery. The team also noted that illustrating a country with a high number of links to its neighbors can denote particularly hostile relations. This suggests that it’s important to pay close attention to details in data visualizations, as they can have a major impact on audiences’ thinking.

“In the midst of the ‘rapid rise’ of emotional appeals in data visualization, and the ubiquity of data visualizations among conspiratorial groups,” the authors write, “we point to a need to examine the unique persuasive power of charts and maps, which often take advantage of a (falsely) assumed trustworthiness or objectivity of data.”

In a statement Correll said, “There are lots of really subtle ways that we convince ourselves about what’s true in the world.” ![]()

Lead illustration by Udo Keppler / Wikimedia Commons