Last week, cooperation took a fall. A United Nations treaty to reduce plastic production melted in the sun of opposition from countries who make most of the world’s plastic, including the United States.

In the middle of the last century, we learned to master the chemistry of carbon. It was a triumph born of war and industry, of oil wells and laboratories, and its most versatile offspring was plastic: a material as supple as imagination and as enduring as geological time. We made it to last forever—and it does. If only we could have foreseen the problem.

At the entrance to The Blue Paradox, an exhibit at the Griffin Museum of Science and Industry in Chicago, you pass beneath a canopy of 1,278 fish, each sculpted from plastic waste by the artist Aurora Robson. The installation is called Emergence, and it is aptly named. We can emerge from the plastic crisis. But first we must submerge in it.

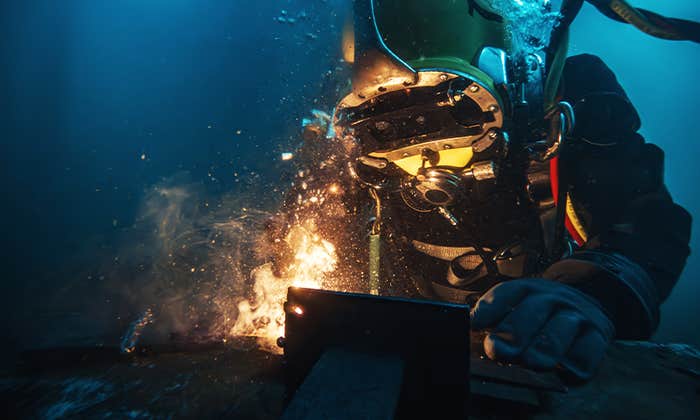

Paradox is a walk into a mirror held up to the modern world. Photo courtesy of the Griffin Museum of Science and Industry.

You step into an immersive ocean—waves of light, whispering currents of sound, the rhythm of breath and tide. This is not decoration; it is a reorientation. The ocean is not “out there.” It is the Earth’s primary engine of life. It covers more than 70 percent of the planet’s surface, produces half the oxygen we breathe, and regulates the climate that makes our existence possible. To walk beneath its surface, even virtually, is to be reminded that we are not masters of nature, but citizens of it.

Each year, 14 million metric tons of plastic enter the ocean. It is a number so large that it ceases to have meaning. The exhibit gives it form: photographs of rivers in Indonesia choked with shampoo bottles, statistics about microplastics found in whales and wombs, maps of the five great ocean gyres where garbage whirls in slow gyroscopic dances. It is one thing to know that plastic is durable. It is another to see it outlasting coral.

To encounter The Blue Paradox—created by SC Johnson and Conservation International—is not to encounter merely an ecological problem, nor a scientific phenomenon. It is to walk into a mirror held up to the modern world.

You are asked not to simply observe plastic, but to reckon with it.

The exhibit’s interactive displays allow you to trace the journey of a plastic bottle from factory to landfill, from coastline to open sea. They allow you to calculate your own plastic footprint. A ticker counts the tons of plastic produced since you entered the exhibit. A conveyor belt pours out plastic waste in a ceaseless flood. The experience is not overwhelming by accident. It is designed to provoke the disquiet of truth. It succeeds.

But, as you wade through the virtual waste, the narrative turns to paradox—the exhibit’s title. Plastics is a villain. It’s in our waterways, clothes, food, and even blood. But it’s also a marvel. It makes modern medicine possible. It stores vaccines and sterile instruments. It preserves food, reduces weight in cars, and shelters electronics.

Plastic’s problem is not in its invention, but in its abandonment. We made a material that endures longer than civilizations, and we built our culture to use it once and throw it away.

The exhibit returns you to the possibility of hope. Here are the solutions—small, imperfect, but real. Alternatives to plastic. Reuse systems. Legislation. Education. A wall of names, digital and glowing, records the pledges made by guests: to reduce, to reuse, to speak out, to vote. It is a quiet room, and yet it hums with potential.

For its part, SC Johnson has chosen to confront its history rather than obscure it. “Plastic is one of the most useful materials we’ve ever invented,” says SC Johnson CEO Fisk Johnson. To solve the crisis, Johnson adds, “you have to get everyone in the plastic recycling loop collectively. And it all has to be done at scale.” This is not a call for perfection, but for cooperation.

How will we overcome? Exhibits like The Blue Paradox can point the way. Corporations that produce plastic aren’t the final obstacle. They can change.

As you walk through the Blue Paradox exhibit, in shifting light and with the floor trembling beneath your feet, you are asked not to simply observe plastic, but to reckon with it. And that means to reckon with yourself, with the world you want. ![]()

Lead photo courtesy of the Griffin Museum of Science and Industry