If you’ve ever gazed deeply into your pup’s eyes and felt like you were riding the same emotional wavelength, you might have missed the mark: People’s moods seem to cloud how they perceive those of their dogs.

Research on people’s readings of canine feelings has yielded mixed results—some work has suggested that we can clearly discern them via behavior or facial expressions, while other results point to factors that can bias our interpretations. These include the animal’s environment and one’s familiarity with dogs, the latter of which could lead people to overlook signs that dogs are unhappy.

Another element that may cloud our judgement of dog emotions: our own moods. People’s feelings can shape how they perceive those of other individuals, researchers have found. A team from Arizona State University wanted to learn if this same phenomenon applied to human perceptions of dogs, too.

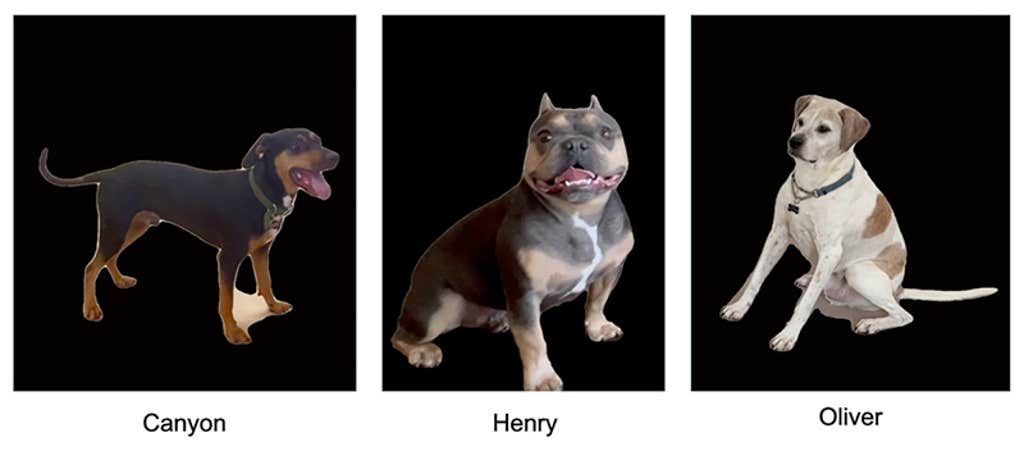

The researchers recruited 600 participants, all undergraduate psychology students, who they surveyed over two experiments. In the first experiment, participants were split into groups and instructed to look at images of people, landscapes, and other scenes meant to spark positive, neutral, or negative emotions. Then, they watched a series of video clips of three dogs that were filmed in situations that their owners believed would make the dogs feel positive, neutral, or negative emotions. In a survey, the subjects estimated how happy, sad, calm, or excited the dogs felt. Ultimately, the participants’ initial mood did not significantly affect their gauge of the dogs’ moods.

In a second experiment, the researchers induced positive, neutral, or negative moods in participants by showing them photos of dogs that other people had rated their own emotional responses to in a previous paper. Then, this second group watched the same dog videos as in the first experiment and estimated the animals’ emotional states. This had an intriguing effect—participants in a happy mood tended to guess that the dogs were sadder, and people in a low mood rated them as happier.

Read more: “Why Do Some People Look Like Their Dogs?”

“This was a surprising finding,” the authors wrote in the paper, which was published in PeerJ. The dog images shown in the beginning of the second experiment “significantly altered their emotional interpretations, but in the opposite direction from that typically observed.” The results suggest that humans’ understanding of dog moods is more likely to be swayed by dogs themselves than other stimuli that can affect our emotions.

The researchers noted that their paper “may have uncovered a novel dynamic” through these cross-species observations. They also found that the dog videos boosted the subjects’ moods, which aligns with previous research—anecdotally, many people can attest to the power of pet clips to cheer them up.

A few caveats: the participants were all college undergrads, the videos only included three dogs, and their affective states were all “assumed” based on owner interpretation.

In future studies, the scientists hope to compare how gazing at images of different creatures beforehand, including domesticated cats and wild animals, affects people’s emotional perceptions of pets. Ultimately, the authors wrote, refining our grasp of animal sentiments can “hold real-world implications for how we perceive, empathize with, and care for dogs and other animals.” ![]()

Enjoying Nautilus? Subscribe to our free newsletter.

Lead image: nancy sticke / Pixabay