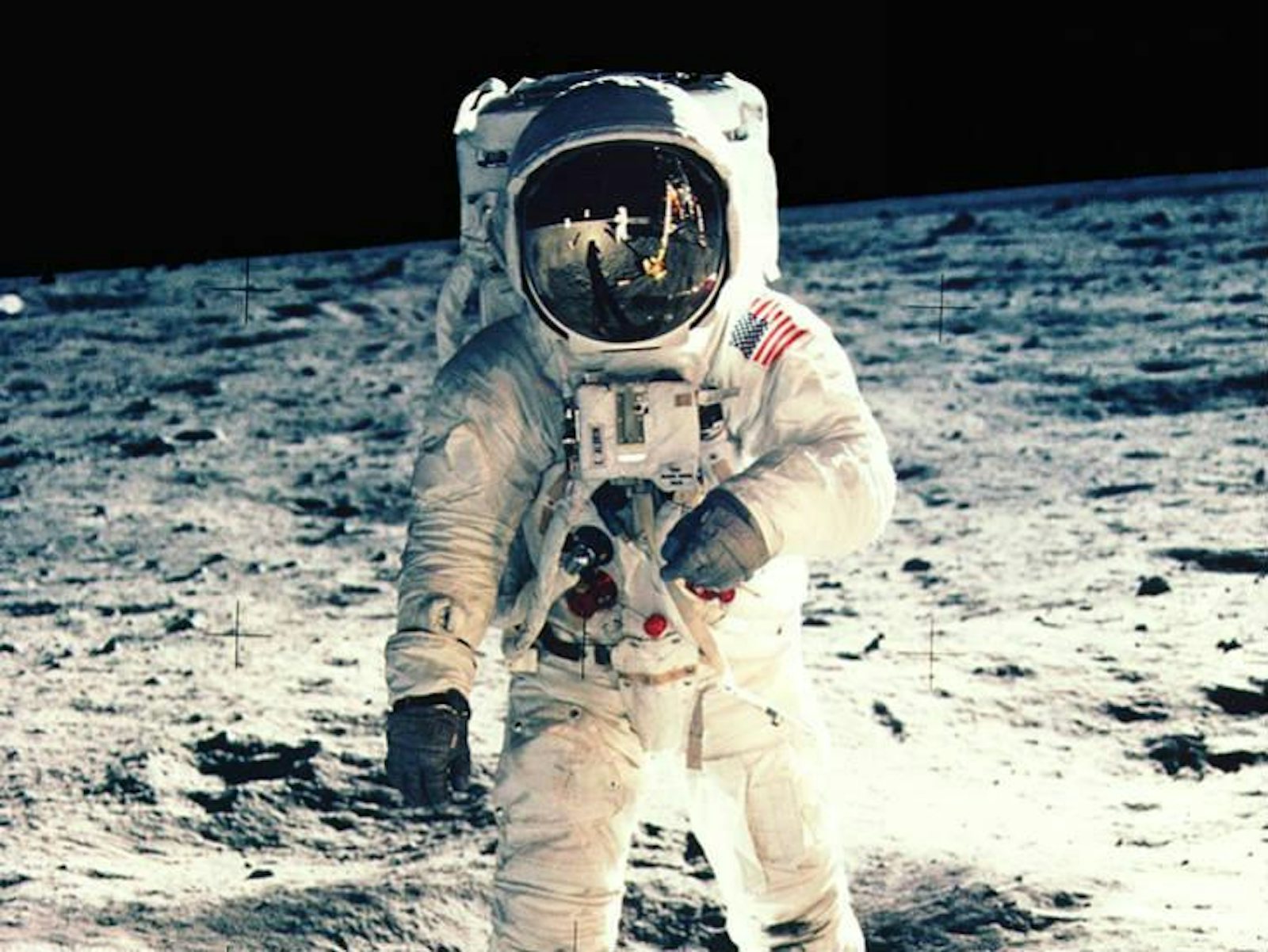

Perhaps no recorded phrase has been so heavily analyzed, so dredged for missing information, as Neil Armstrong’s words when he took his first step on the Moon. In case you’ve been living under a rock for the last 40-odd years, they were (drumroll), “One small step for man, one giant leap for mankind.”

Or at least, that’s how they sound to most people. The uncertainty arises over the fact that the phrase would make much more sense—would make clearer the contrast between Armstrong’s first physical step on the powdery moondust and the space program’s vast accomplishments—if there were an article in there: specifically, an “a” before “man.” For decades, people have said that Armstrong flubbed his line, while NASA maintained, at least at first, that the word is missing from the mission recording “because of static.” Armstrong himself said he’d been “misquoted.”

And the controversy won’t die. Every few years, delightfully nerdy posts go up at the linguistics blog Language Log, analyzing the latest theories as to what happened up there, on the recording, and in listeners’ minds to render this particular impression of those 10—or 11—words. In 2006, the blog published an exchange with Armstrong’s biographer, who noted:

“You should take into consideration…that Neil comes from northwestern Ohio. I come from northeastern Indiana, only 60 miles from where Neil grew up. There is a regional accent to consider. ‘For a’ is often expressed as ‘foruh,’ virtually as one syllable. Personally, that is my theory.”

This week, that theory gained credence thanks to a detailed linguistic study of Ohio accents presented at the International Congress on Acoustics meeting in Montreal. In the study, entitled “One small step for (a) man: Function word reduction and acoustic ambiguity,” researchers analyzed recordings of 40 Ohioans from near Armstrong’s hometown of Wapakoneta speaking conversationally. Looking at the 191 instances of “for a,” they found that indeed, the “a” in “for a” tended to get swallowed by the speakers’ “r” sound. And when “for” is spoken alone, the “r” is quite drawn out, to the extent that “for” and “for a” often last for the same amount of time. They conclude that it’s very likely that Armstrong thought, and spoke, the words “for a,” but his accent rendered the phrase so that to the ears of nearly everyone else, it sounded like “for.”

“Every time we listen to speech and think we understand a sentence, we are performing a miraculous task.”

The researchers point out, almost as an afterthought, that it’s amazing that we aren’t uncertain about words more often. The fact that we are able to dissect words and meaning from the flow of air we squeeze out through a tube of exquisitely vibrating flesh is a testament to the sophistication of our brains’ pattern recognition abilities. “Every time we listen to speech and think we understand a sentence, we are performing a miraculous task, which is to take what is actually a continuous acoustic signal, break up that signal into somewhat arbitrary parts, and map those parts to our memories of all the words that we know in the language,” one of the researchers said in a prepared statement. “We need only look at computer speech recognition and how it succeeds and how it largely often fails to see how very difficult that problem is.” This point raises the possibility that if computers take on a bigger role in processing and interpreting our communications in the future, as seems likely, then linguistic uncertainty may only become a bigger problem in our lives.

And Armstrong? According to his biographer, he finally said that he preferred the historic quote to be rendered, “One small step for [a] man, one giant leap for mankind.” But while we know what he meant to say as he took that small step, we may never know with certainty what words were actually pronounced, in the messy spaces between speaker and listener, between one accent and another.

Veronique Greenwood is a former staff writer at DISCOVER Magazine. Her work has appeared in Scientific American, Popular Science, and the sites of Time, The Atlantic, and The New Yorker. Follow her on Twitter here.