I was naked. So was Laura,” begins one dream of the more than 20,000 collected in G. William Domhoff’s DreamBank. “I was re-stringing an unvarnished electric bass, so I guess it was naked, too. At one point I put a screw in to secure a string, but then realized I wasn’t holding the bass but Laura…” The dream is one of many “naked” entries in the database, and Domhoff says dreams about being naked or exposed in public in ways that betray a fear of embarrassment are widely reported. But why?

Domhoff, a distinguished professor emeritus specializing in psychology at the University of California-Santa Cruz, has spent years collecting self-reported dreams in journals and laboratory settings, meticulously tagging and cataloguing each one. An outdoor setting, for example, is marked with an OU, a familiar character with a K, and physical activity with a P. Individual dreams can then be described with their own idiosyncratic combination of labeled elements. Domhoff calls this coding system “quantitative content analysis.” He’s concluded that at least some dreams have universal elements related to common human preoccupations and concerns.

Some “typical” dreams long studied for their figurative meaning—such as dreams where you fly under your own power, or where your teeth fall out—don’t occur nearly as often as people think (flying dreams, for example, make up only about one-half of 1 percent of all dreams). But many people dream about being naked, or about physical journeys that might stand in for fraught everyday dilemmas, such as being thwarted in a quest for success. “We are walking down hall after hall,” one of the dreams in Domhoff’s database reads. “We are looking for a restaurant. We climb laboriously up ladders and get to a top floor to find out the restaurant is closed. I am upset and afraid of going back down.”

What we dream about at age 20 isn’t all that different from what we dream about at age 80, says Domhoff. And the dream worlds of an American, a Liberian, and a Czech—regardless of their divergent life experiences—will look more similar than not. “They dream of something in the past they regret or miss, and they dream about future worries like an exam, the health of their baby or children,” Domhoff says. “They dream most often about the things that concern them the most.” Domhoff’s database entries are about twice as likely to take place in familiar settings as in unfamiliar ones, and more than 90 percent of its dream characters are humans rather than animals or fantastical creatures. But, as Jung might have predicted, the collection clearly reveals that people dream about a lot of the same types of things.

The psychoanalysts have a vested interest in destroying my argument.

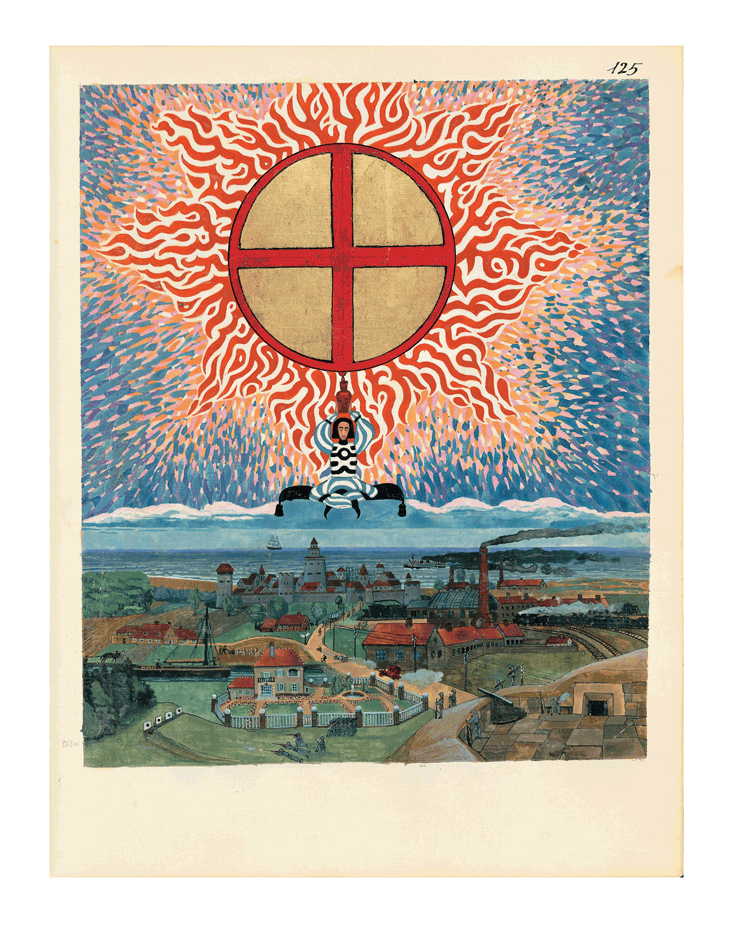

The idea of common nature to dreams extends back to at least the Swiss psychoanalyst Carl Jung, who once told an audience that, “we are all badly in need of the symbolic life. Only the symbolic life can express the need of the soul.” This symbolic life, Jung believed, is shared among humans and animals in the form of a collective unconscious, and expressed through a set of universal images and motifs that can appear in dreams. In his later years, Jung became obsessed with these symbols and filled a secret diary with his own dreams and fantasies. It was published 48 years after his death under the title Red Book, and has since made the rounds of the international museum scene. Jung’s own dreams, together with the experience he gained from his patients, informed his theories.

Modern dream analysis relies on rather more systematic methods of data collection, such as recording nighttime brain activity and coding dream reports that sleepers supply. But while the techniques have changed, the observation of common images and themes persists. Tufts University psychiatrist Ernest Hartmann, now deceased, studied how the 9/11 attacks on New York City affected the dreams of 44 people around the country who had been recording their dreams daily for years. Comparing their last 10 dreams pre-9/11 with the first 10 dreams they described after the attacks, he found a post-9/11 dreamscape that was more intense, frequently featuring general or metaphorical visions of attack, such as being overtaken by wild animals or pursued by monsters.

Given that dreams have at least some common elements, where do they come from? Are these qualities the result of a collective unconscious, Jung’s innate mental framework with its universal human themes (the monster or “dark side,” the victorious hero, the journey to a distant land)? Or are there other, more straightforward explanations?

Harvard psychiatrist and professor emeritus Allan Hobson bristles at the idea that common images in our dreams might be the products of a Jungian collective unconscious. “I think of that as sort of amusing literary speculation,” he says. Hobson, who calls himself a “thoroughgoing biologist,” has spent years studying the neural genesis of dreams in the lab with the help of tools like electroencephalography (EEG) machines, which record sleeping subjects’ brain waves. He has established himself as a sort of anti-Freud, countering the speculative flights of old-school dream analysis with the thrust of objective data.

“If you don’t study the brain, you aren’t doing science these days,” he says. “The psychoanalysts have a vested interest in destroying my argument.” That argument is that dreams are essentially the product of chaotic brain signals that the forebrain—which governs higher intellectual function in waking life—pieces together into narratives. Hobson argues that dreams therefore do have psychological meaning, but they don’t bubble up out of a pre-existing collection of themes in the subconscious. Instead, they mostly reflect conscious thoughts and concerns from day-to-day life: They are transparent, if garbled, depictions of real issues or people.

He was sitting in a rowboat, watching fishermen chop off sharks’ fins and toss the dying animals back into the sea.

Hobson readily acknowledges similarities in dreams the world over, but he doesn’t think that’s any reason to take Jung at face value. Rather than assuming dream themes come from an inherited set of mental categories—a theory for which he thinks there is little evidence—he attributes dream similarities at least in part to basic neural wiring. Human brains, he says, all process emotion essentially the same way, so it’s not surprising that dreams deal in common emotional concerns like fear and anxiety. “We’re all humans—we all have emotions. In dreaming, emotions are more strongly activated probably than recent memory.” Domhoff echoes many of Hobson’s concerns, pooh-poohing modern “Freudians and Jungians” and their views on dreams (“I would say they are talking ancient history”).

But University of Cape Town neuropsychologist Mark Solms doesn’t write Jung off quite so easily. While he doesn’t outright endorse the idea of a universal collective unconscious, he’s more sympathetic to the prospect than Hobson. There are “absolutely stereotyped dreams that human beings have everywhere,” he says. “That points to some sort of collective content.”

In studies of patients with brain injuries, Solms has discovered that people stop dreaming only when certain higher regions of the brain are damaged—particularly areas that control urges, drives, and motivation, which he calls the seeking system. This system, according to Solms’ theory, imparts volition and intentionality to dreams, and makes them point to things we desire. “There’s good reason to believe that the thing that drives dreams is the thing that drives the whole engine of your mind,” says Solms. “It’s not random, it’s not neutral. It has something to do with matters that concern you.” This, in turn, can lead to dreams about universal inner experiences. There are various common, emotion-fueled dream situations, Solms thinks, that align at least somewhat with Jung’s concept of a collective unconscious. “There are certain recurring fears in dreams, certain situations you find yourself in: ‘I forgot to feed the baby,’ ‘I left the dog at home.’ I don’t think it’s exactly what Jung meant, but it’s not far away.”

Hobson has long clashed with Solms on the question of whether dreams might have hidden meaning. “Any speculation [about hidden meanings] is worthy of literature,” Hobson says. “If you know that the dream is meaningful on its surface, why bother interpreting it?” But Solms—like many traditional psychoanalysts—thinks dreams may reveal important wishes and conflicts we suppress when we’re awake. In dreaming, Solms says, “your mind is loosened up, so you might allow yourself to think things or make connections that you wouldn’t in a more focused, goal-directed type of thinking.” You might never consciously admit to yourself that you’re unhappy with a prestigious, high-paying job, for instance, but you might dream about a 50-foot Godzilla smashing your office building to bits.

It’s this latter type of narrative, according to Chicago psychotherapist Jeffrey Sumber, that reveals why paying close attention to our dreams is so important. Sumber, who has studied dream interpretation at Zurich’s Jung Institute, specializes in the kind of dream analysis Hobson scoffs at: He helps his clients mine their dreams for subconscious insights that may otherwise be inaccessible to them. Like Jung, Sumber believes that some dreams clearly have universal qualities—not just because human brains have the same biological hardware for processing emotion, but because humans share a “symbolic life,” a set of common themes and motifs we use to convey our experience. “I believe there are archetypal dreams that reflect the human experience and the collective unconscious.” He adds, though, that such universal dream themes also need to be examined in light of their personal significance to the dreamer.

Instead of assuming, as Hobson does, that most dreams have fairly obvious connections to everyday life, Sumber guides dreamers in ferreting out interpretations that might not be readily apparent. “I encourage people to be their own analyst: ‘What do I think this dream means to me? Is this an “oatmeal” dream, or is it a big dream?’ ” He thinks thorough consideration of one’s own dreams can be life-changing because of the submerged truths they reveal. He himself has a fear of sharks, but a dream he had one night, in which he was sitting in a rowboat, watching fishermen chop off sharks’ fins and toss the dying animals back into the sea, helped him cope with that fear. Reflecting on the dream and its deeper meaning proved transformational, Sumber says. The sharks likely represented Jung’s universal “monster” dream theme, and his sadness at their plight led him to a place of unexpected empathy for his own dark side and that of others.

While disagreements like these persist, most dream theorists do agree on this point: Dreams often have a fundamentally emotional nature. The limbic system, which governs emotion, is highly engaged in dreamers—particularly the amygdala, which helps us process unpleasant or intense feelings like fear and aggression. “All the contemporary theories of dreaming,” writes sleep researcher Rosalind Cartwright in The Twenty-Four Hour Mind, “emphasize that dreams are not about prosaic themes … but about emotion.” Hobson acknowledges the importance of emotions to dreaming, as does Hartmann, who has suggested that the striking central images in post-9/11 dreams sprang from intense emotion. His study, he wrote, “supports the idea that the dream image is an emotionally guided construction or creation, not a replay of waking experience.”1 This suggests the tantalizing possibility that common dream themes may reflect similarities in the human emotional experience—which persist despite variations in the external trappings of language and culture—and that the mental territory we all share is more vast and profound than that which separates us. Which is very Jungian indeed.

Elizabeth Svoboda is a writer in San Jose, California, and the author of What Makes a Hero?: The Surprising Science of Selflessness.

Reference

1. Hartmann, E. & Brezler, T. A systematic change in dreams after 9/11/01. Sleep 31, 213-218 (2008).