A few years ago there was a woman in my life—let’s call her Tanya—and we had hooked up one night in Los Angeles. We’d both attended a birthday party, and when things were winding down, she offered to drop me off at home. We had been chatting and flirting a little the whole night, so I asked her to come in for a drink. At the time, I was subletting a pretty nice house up in the Hollywood Hills. It was kind of like that house De Niro had in Heat, but a little more my vibe than the vibe of a really skilled robber who takes down armored cars. I made us both a nice cocktail and we took turns throwing on records while we chatted and laughed. Eventually we started making out, and it was pretty awesome. I remember drunkenly saying something really dumb when she was leaving, like, “Tanya, you’re a very charming lady …” She said, “Aziz, you’re a pretty charming guy, too.” The encounter seemed promising, as everyone in the room had agreed: We were both charming people.

I wanted to see Tanya again and was faced with a simple conundrum that plagues us all: How and when do I communicate next? Do I call? Do I text? Do I send a Facebook message? Do I send up a smoke signal? How does one do that?

Eventually I decided to text her, because she seemed to be a heavy texter. I waited a few days, so as not to seem overeager. I found out that the band Beach House, which we listened to the night we made out, was playing that week in L.A., so it seemed like the perfect move.

Here was my text:

“Hey—don’t know if you left for NYC, but Beach House playing tonight and tomorrow at Wiltern. You wanna go? Maybe they’ll let you cover The Motto if we ask nicely?”

A nice, firm ask with a little inside joke thrown in. (Tanya was singing the Drake song “The Motto” at the party and, impressively, knew almost all the lyrics.)

A few minutes went by and the status of my text message changed to “read.” My heart stopped. This was the moment of truth. I braced myself and watched as those little iPhone dots popped up. The ones that tantalizingly tell you someone is typing a response, the smartphone equivalent of the slow trip up to the top of a roller coaster. But then, in a few seconds—they vanished. And there was no response from Tanya.

Hmmm … What happened? A few more minutes go by and … Nothing. Fifteen minutes go by … Nothing. My confidence starts going down and shifting into doubt. An hour goes by … Nothing. Two hours go by … Nothing. Three hours go by … Nothing. A mild panic begins. I start staring at my original text. Once so confident, now I second-guess it all.

I’m so stupid! I should have typed “Hey” with two y’s, not just one! I asked too many questions. What was I thinking? Oh, there I go with another question. Aziz, WHAT’S UP WITH YOU AND THE QUESTIONS?

Then I realized something interesting: The madness I was descending into wouldn’t have even existed 20 or even 10 years ago. There I was, maniacally checking my phone every few minutes, going through this tornado of panic and hurt and anger all because this person hadn’t written me a short, stupid message on a dumb little phone.

Texting conditions our minds; we expect our exchanges to work differently than they did with phone calls.

Modern romance is stressful—especially when it comes to texting, which is on course to be the new norm for asking someone out. In 2010 only 10 percent of young adults used texts to ask someone out for the first time, compared with 32 percent in 2013. And so, more and more of us find ourselves sitting alone, staring at our phone’s screen with a whole range of emotions. But in a strange way, we are all doing it together, and we should take solace in the fact that no one has a clue what’s going on. So, I decided to look into it myself, but I knew that bozo comedian Aziz Ansari probably couldn’t tackle the topic on my own, and so I teamed up with New York University sociologist Eric Klinenberg. We designed a massive research project during 2013 and 2014, which involved conducting focus groups and interviews with people worldwide, and also interviewing eminent researchers who have dedicated their careers to studying modern romance. We learned a lot about finding love today, including what to do once you fire off a text or receive one.

One area where there was a lot of debate was the amount of time one should wait to text back. Several people subscribed to the notion of doubling the response time. (They write back in five minutes, you wait 10, etc.) This way you achieve the upper hand and constantly seem busier and less available than your counterpart. Others thought waiting just a few minutes was enough to prove you had something important in your life besides your phone. Some thought you should double, but occasionally throw in a quick response to not seem so regimented (nothing too long, though!). Some people swore by waiting 1.25 times longer. Others argued they found three minutes to be just right. There were also those who were so fed up with the games that they thought receiving timely responses free of games was refreshing and showed confidence.

But does this stuff work? Why do so many people do it? Are any of these strategies really lining up with actual psychological findings?

The Power of Waiting

In recent years behavioral scientists have shed some light on why waiting techniques can be powerful. Let’s first look at the notion that texting back right away makes you less appealing. Psychologists have conducted hundreds of studies in which they reward lab animals in different ways under different conditions. One of the most intriguing findings is that “reward uncertainty”—in which, for instance, animals cannot predict whether pushing a lever will get them food—can dramatically increase their interest in getting a reward, while also enhancing their dopamine levels so that they basically feel coked up.

If a text back from someone is considered a “reward,” consider the fact that lab animals who get rewarded for pushing a lever every time will eventually slow down because they know that the next time they want a reward, it will be waiting for them. So basically, if you are the guy or girl who texts back immediately, you are taken for granted and ultimately lower your value as a reward. As a result, the person doesn’t feel as much of an urge to text you or, in the case of the lab animal, push the lever.

Texting is a medium that conditions our minds in a distinctive way, and we expect our exchanges to work differently with messages than they did with phone calls. Before everyone had a cell phone, people could usually wait a while—up to a few days, even—to call back before reaching the point where the other person would get concerned. Texting has habituated us to receiving a much quicker response. From our interviews, this time frame varies from person to person, but it can be anywhere from 10 minutes to an hour to even immediately, depending on the previous communication. When we don’t get the quick response, our mind freaks out.

Natasha Schüll, an anthropologist who was with the Massachusetts Institute of Technology at the time, studies gambling addiction and specifically what happens to the minds and bodies of people who get hooked on the immediate gratification that slot machines provide. When we met in Boston, she explained that unlike cards, horse races, or the weekly lottery—all games that make gamblers wait (for their turn, for the horses to finish, or for the weekly drawing)—machine gambling is lightning fast, so that players get immediate information.

“You come to expect an instant outcome, and you stop tolerating any delay,” says Schüll. She drew an analogy between slot machines and texting, since both generate the expectation of a quick reply. “When you’re texting with someone you’re attracted to, someone you don’t really know yet, it’s like playing a slot machine: There’s a lot of uncertainty, anticipation, and anxiety. Your whole system is primed to receive a message back. You want it—you need it—right away, and if it doesn’t come, your whole system is like, ‘Aaaaah!’ You don’t know what to do with the lack of response, the unresolved outcome.”

Schüll said that texting someone is very different from leaving a message on a home answering machine, which we used to do in the days before smartphones. “Time-wise, and also emotionally, leaving a message on someone’s machine was more like buying a lottery ticket,” she explained. “You knew there would be a longer waiting period until you found out the winning numbers. You weren’t expecting an instant callback and you could even enjoy that suspense, because you knew it would take a few days. But with texting, if you don’t hear back in even 15 minutes, you can freak out.”

When you are texting someone less frequently, you are, in effect, creating a scarcity of you and making yourself more attractive.

Schüll told us that she has experienced this waiting distress firsthand. Several years ago she was texting with a suitor, someone she’d starting dating and was really into, and he gave every indication that he was really into her too. Then, out of nowhere, the guy went silent. She didn’t hear back from him for three days. She got fixated on the guy’s disappearance and had trouble focusing or even participating in ordinary social life. “No one wanted to hang out with me,” she said, “because I was just obsessed, like, Where is this guy?!”

Eventually the guy reached out and she was relieved to find out that he’d actually legitimately lost his phone, and since that’s where he’d stored her number, he had no other way of getting in touch with her.

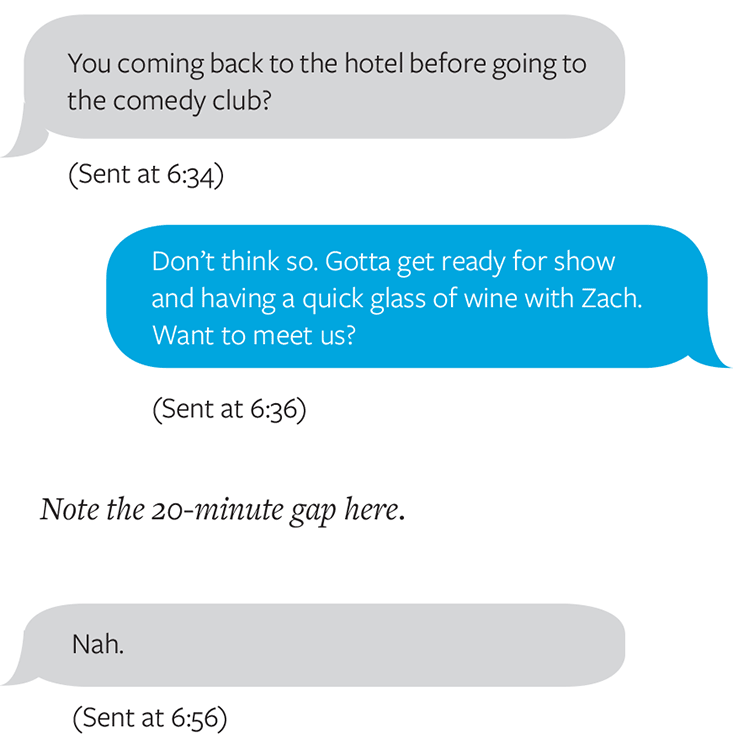

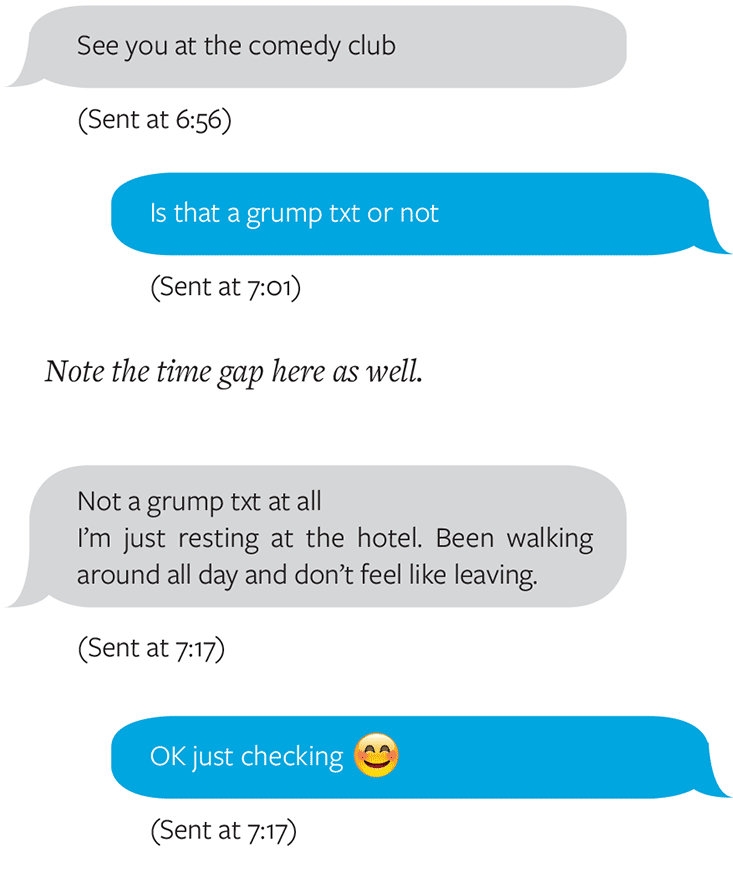

“With a phone call, three days of silence probably wouldn’t drive you that crazy, but with my mind habituated to texting, the loss of that reward … Well, it was three days of pure hell,” she said. Even people in relationships experience this anxiety with texting. In my own relationship, which is a committed, loving partnership, I’ve experienced several instances of a delay in text causing uneasiness. Here’s an example:

In the gap after “Want to meet us?” I was sure she was mad about something. Her responses had been pretty immediate, and it seemed like her pause was an indicator that something was wrong and that I should have been going to the hotel or something.

Again, when she didn’t respond after “Is that a grump txt or not” I was certain she was grumpy, because why wait so long to tell me she’s not grumps? All of this change in my perception of her feelings and my own mood was purely because of the temporal differences in texting.

If the effect is this powerful for people in committed relationships, it makes sense that all the psychological principles seem to point to waiting being a strategy that works for singles who are trying to build attraction.

For instance, let’s say you are a man and you meet three women at a bar. The next day you text them. Two respond fairly quickly, and one of them does not respond at all. The first two women have, in a sense, indicated interest by writing back and have, in effect, put your mind at ease. The other woman, since she hasn’t responded, has created uncertainty, and your mind is now looking for an explanation for why. You keep wondering, Why didn’t she write back? What’s wrong? Did I screw something up? This third woman has created uncertainty, which social psychologists have found can lead to strong romantic attraction.

The team of Erin Whitchurch, Timothy Wilson, and Daniel Gilbert conducted a study where women were shown Facebook profiles of men who they were told had viewed their profiles. One group was shown profiles of men who they were told had rated their profiles the best. A second group was told they were seeing profiles of men who had said their profiles were average. And a third group was shown profiles of men and told it was “uncertain” how much the men liked them. As expected, the women preferred the guys who they were told liked them best over the ones who rated them average. (The reciprocity principle: We like people who like us.) However, the women were most attracted to the “uncertain” group. They also later reported thinking about the “uncertain” men the most. When you think about people more, this increases their presence in your mind, which ultimately can lead to feelings of attraction.

Another idea from social psychology that goes into our texting games is the scarcity principle. Basically, we see something as more desirable when it is less available. When you are texting someone less frequently, you are, in effect, creating a scarcity of you and making yourself more attractive.

What happened with Tanya, though?

The thing to remember with this nonsense is, despite all your second-guessing about the content or timing of your message, sometimes it’s just not your fault and other factors are at play. When I was dealing with the Tanya situation, one friend gave me the best advice, in hindsight. He said, “A lot of times you’re in these situations and you second-guess the things you said, did, or wrote, but sometimes it just has to do with something on their end that you have no clue about.”

A few months later I ran into Tanya. We had a lot of fun together and she eventually told me that she was sorry she didn’t get back to me that time. Apparently at the time she was questioning her entire sexual identity and was trying to figure out if she was a lesbian.

Well, that was definitely not a theory that crossed my mind. We ended up hooking up that night, and this time she said there would be no games. I texted her a few days later to follow up on this plan. Her response: silence.

Aziz Ansari is an actor and comedian, best known for his role on Parks and Recreation and the Netflix series Master of None, which he created, writes, and stars in. Modern Romance is his first book.

Eric Klinenberg is a professor of sociology at New York University with an interest in urban studies, culture, and media. He has written five books in addition to Modern Romance.

From Modern Romance

by Aziz Ansari with Eric Klinenberg, published by Penguin Press, an imprint of Penguin Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House LLC.

Copyright © 2015 by Modern Romantics Corporation.