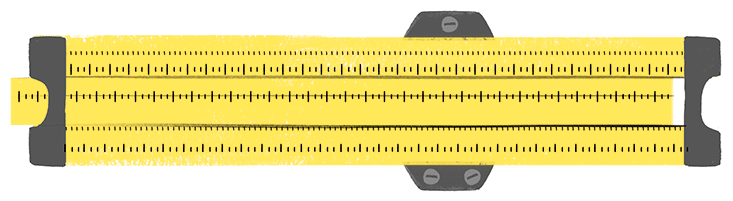

There is nothing in the world more perfect than a slide rule. Its burnished aluminum feels cool against your lips, and if you hold it level to the light you can see God’s most perfect right angle in each of its corners. When you tip it sideways, it gracefully transfigures into an extravagant rapier that is also retractable with great stealth. Even a very little girl can wield a slide rule, the cursor serving as a haft. My memory cannot separate this play from the earliest stories told to me, and so in my mind I will always picture an agonized Abraham just about to almost sacrifice helpless little Isaac with his raised and terrible slide rule.

I grew up in my father’s laboratory and played beneath the chemical benches until I was tall enough to play on them. My father taught 42 consecutive years’ worth of introductory physics and earth science in that laboratory, nestled within a community college deep in rural Minnesota; he loved his lab, and it was a place that my brothers and I loved also.

The walls were made of cinder blocks slathered in thick cream-colored semigloss paint, but you could feel the texture of the cement underneath if you closed your eyes and concentrated. I remember deciding that the black rubber wainscoting must have been attached with adhesive, because I couldn’t find any nail holes anywhere when I measured its whole length with the yellow surveying tape that extended to a full 30 meters. There were long workbenches where five college boys were to sit side by side, all facing the same direction. These black countertops felt cool as a tombstone and were made of something just as timeless, something that acid couldn’t burn and a hammer couldn’t smash (but don’t try). The benches were strong enough for you to stand on the edge of and couldn’t be scratched even with a rock (but don’t try).

Evenly spaced across the benches were braces of impossibly shiny silver nozzles with handles that took all your strength to turn 90 degrees, and when you did the one that said “gas” did nothing because it wasn’t hooked up, but the one that said “air” blew with such an exhilarating rush that you kind of wanted to put your mouth on it (but don’t try). The whole place was clean and open and empty, but each drawer contained a fascinating array of magnets, wire, glass, and metal that were all useful for something; you just had to figure out what it was. In the cupboard by the door there was pH testing tape, which was like a magic trick only better because instead of just showing a mystery it also solved one: You could see the difference in color and thus pH between a drop of spit and a drop of water or root beer or urine in the bathroom but not blood because you can’t see through it (so don’t try). These were not kids’ toys; they were serious things for grown-ups, but you were a special kid because your dad had that huge ring of keys, so you could play with the equipment anytime you went there with him, because he never, ever said no when you asked him to take it all out.

In my memory of those dark winter nights, my father and I own the whole science building, and we walk about like a duke and his sovereign prince, too preoccupied in our castle to bother about our frozen duchy. As my father prepared for class the next day, I would work backward through each canned experiment and demonstration, making sure the college boys would have the easy success toward which they were predisposed. We pored over the equipment and fixed what was broken, and my father taught me how to preemptively take things apart and study how they work, so that as they inevitably failed I’d be able to restore them. He taught me that there is no shame in breaking something, only in not being able to fix it.

At 8 o’clock we would start our walk home, so I could be in bed by 9. First we’d stop by my father’s tiny, windowless office, which was bare of decoration except for the pencil holder that I had made for him out of clay. From there we’d collect our coats, hats, scarves, and the other things that my mother had knitted for me because she had never had decent ones when she was a little girl. As I wrestled my sturdy boots over an extra pair of socks, the smell of warm, wet wool mixed with that of wood shavings as my father sharpened each of the pencils that we had dulled. He would then briskly button up his big coat and don his deerskin mittens and tell me to check that my hat was fully covering both of my ears.

When you grow up around people who don’t speak very much, what they do say to you is indelible.

Always the last to leave the building for the day, he would walk the halls twice, first to confirm that all the doors to the outside were locked, and then to turn off the lights, one by one, as I trotted along behind him, fleeing the pursuing darkness. Finally, at the back entrance, my father would let me reach up and swipe off the last set of light switches, and we’d walk outside. He’d pull the door shut behind us and then check it twice to make sure that the lock had set.

Thus sealed out into the cold, we’d stand on the loading dock and look up at the frozen sky and into the terminal coldness of space and see light that had been emitted years ago from unimaginably hot fires that were still burning on the other side of the galaxy. I didn’t know any of the constellations that people used to name the stars above me, and I never asked what they might be, though I am certain that my father knew each one and the story behind it. We had long since established the habit of not speaking as we walked the 2 miles home; silent togetherness is what Scandinavian families do naturally, and it may be what they do best.

The community college where my father worked was situated at the western end of our little hometown, the incorporated portion of which spanned 4 miles from truck stop to truck stop. My three older brothers and I lived with our parents in a big brick house located south of Main Street, four blocks west of where my father had grown up in the 1920s, eight blocks east of where my mother had grown up in the 1930s, 100 miles south of Minneapolis, and 5 miles north of the Iowa border.

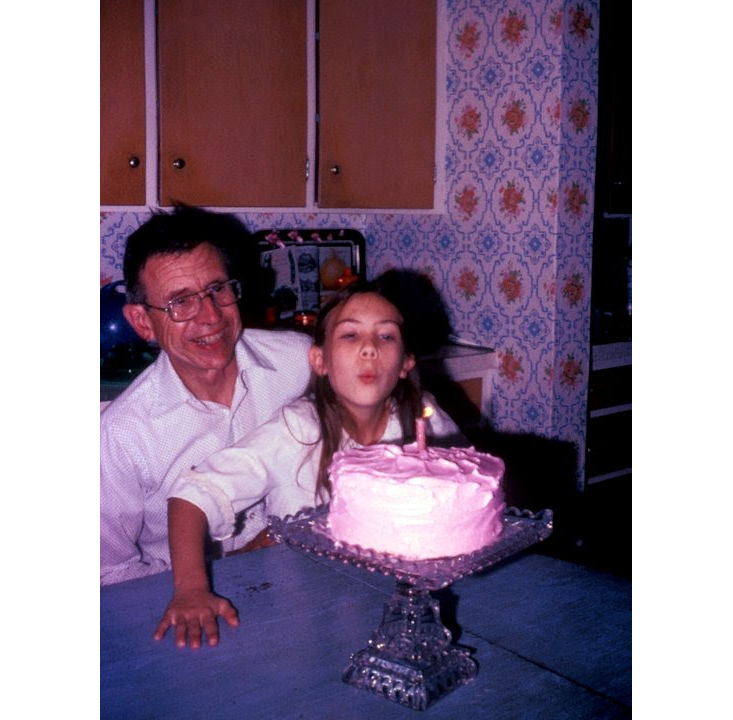

Our path through town took us past the clinic where the same doctor who had delivered me occasionally swabbed my throat to test for strep infections, past the toothpaste-blue water tower that constituted the tallest structure in town, past the high school that was manned by teachers who had once been my father’s students. When we passed under the eavestroughs of the Presbyterian church where my father and mother had their first date at a Sunday School picnic in 1949, were married in 1953, had me baptized in 1969, and where our family spent every Sunday morning without exception, my father would lift me up so that I could break off a thick icicle. I would kick it along like a hockey puck while we walked, and it would ring out every 10 steps or so as it ricocheted off the sides of the hard-packed snowbanks.

We made our way down hand-shoveled sidewalks, past thickly insulated houses that sheltered families who were no doubt partaking of silences similar to our own. In almost every one of these houses lived someone that we knew. From playpen to prom, I grew up with the sons and daughters of the girls and boys whom my mother and father had played with when they were children, and none of us could remember a time when we all hadn’t known each other, even if our deeply bred reticence kept us from knowing much about each other. It wasn’t until I was 17 and moved away to college that I discovered how the world is mostly populated by strangers.

When I heard a weary monster sighing on the other side of town, I understood that it was 23 minutes after 8 o’clock and the train was pulling out of the factory, as it did every night. I heard the great iron brakes wrench and then relax as a string of empty tank cars started to drag northward, toward Saint Paul, where they would each be filled with 30,000 gallons of brine. In the morning we would hear the train return, and the exhausted monster would again sigh as its burden was pumped into the bottomless reservoir of salt made necessary by the factory’s continuous manufacture of bacon.

The train tracks ran north-south, isolating one corner of my little town, upon which still stands what is perhaps the most magnificent slaughterhouse of the Midwest. Starting at its killing chute, upward of 20,000 animals are processed for their meat every single day.

Mine was one of the few families I knew of that was not directly employed by the factory, but our extended lineage had worked there plenty. My great-grandparents, like practically everybody else’s in that town, had come to Minnesota as part of a mass emigration from Norway that began in about 1880. And like everybody else in my hometown, this is pretty much all that I knew about my ancestors. I suspected that they hadn’t relocated to the coldest place on Earth and then taken up disemboweling pigs because things were going well in Europe, but it had never occurred to me to ask for the story.

By the time my father and I had crossed Fourth Street, we could see the front door of our big brick house. It was the house that my mother had dreamed of living in as a child, and after my parents were married they had saved for 18 years in order to buy it. Despite my having walked briskly—it was always an effort to keep up with my father—my fingers were chilled such that I knew it would be painful when they warmed up. Once it gets to a certain point below zero, the thickest mittens in the world won’t keep your hands warm, and I was glad that the walk was almost over. My father turned the heavy iron handle, pushed with his shoulder, and opened our oaken front door. We went inside the house, into a different kind of cold.

In the foyer, I sat down and wrestled off my boots, then began to molt coats and sweaters. My father hung our clothes in the heated closet, and I knew that they would be waiting for me, warm and dry, when it was time to walk to school the following morning. I could hear my mother in the kitchen unloading the dishwasher, the butter knives clanging together as she dropped them into the silverware drawer and then slammed it shut.

I went upstairs, changed into my flannel pajamas, and put myself to bed. My bedroom faced south toward the frozen pond where I would spend all day Saturday ice-skating—if it had warmed up enough by then. The wool carpet was dusky-blue and the walls had been papered in complementary damask. The room had originally been designed for twin girls, with two built-in desks, two built-in vanities, and so on. On the nights when I couldn’t sleep, I would sit at my window seat and trace the feathery ice crystals across the glass with my finger, trying not to look at the vacant seat in front of the other window where a sister should have been.

The fact that I remember so much cold and darkness from my childhood isn’t surprising, given the fact that I grew up in a place where there was snow on the ground for nine months out of each year. Descending into and then surfacing from winter formed the driving rhythm of our lives, and as a child I assumed that people everywhere watched as their summer world died, confident in its eventual resurrection, having been tested so often within a crucible of ice.

Every year I saw the first stuttering flakes of September crescendo into the spilling white heaps of December, then petrify into the deep, icy emptiness of late February, eventually to be varnished as a grand, frictionless expanse by the stinging April sleet. Our Halloween costumes as well as our Easter dresses were sewn such that they could be worn inside our snowsuits, and Christmastime wrapped us in wool, velvet, and more wool. The one summertime activity that I remember vividly is working in the garden with my mother.

In Minnesota, the spring thaw happens all at once when the frozen ground yields to the sun in one day, wetting the spongy soil from within. On the first day of spring, you can reach into the ground and easily pull up great, loose clumps of dirt as if they were handfuls of too-fresh devil’s food cake and watch the fat pink earthworms come writhing out and fling themselves joyfully back into the hole. There is not even a hint of clay within the soils of southern Minnesota; they have lain like a rich black blanket over the limestone of the region for 100,000 years, periodically chased off by glaciers. They are richer than any pre-fertilized potting soil that you can buy at the hardware store; anything will grow in a Minnesota garden, and there’s no need to water or fertilize—the rain and the worms will supply everything that is needed—but the growing season is short, so there’s no time to be wasted.

People are like plants: They grow toward the light. I chose science because it gave me what I needed: a safe place to be.

My mother wanted two things from her garden: efficiency and productivity. She favored sturdy, independent vegetables like Swiss chard and rhubarb, the ones that could be relied upon to yield in abundance and seemed only to thrive in response to frequent harvesting. She had neither the time nor the sympathy required to nurse lettuce or prune tomatoes; instead she preferred the radishes and carrots that could tend to their own needs quietly underground. Even the flowers that she grew were selected for their toughness: the golf ball–sized buds of peonies that spilled out petals as they swelled into pink blossoms the size of cabbages, the leathery tiger lilies, and the fat, bearded irises that barged out of their bulbs without fail, spring after spring after spring.

Each May Day, my mother and I poked individual seeds into the ground, and then a week later we plucked out the ones that hadn’t grown, replacing them and immediately starting over. By the end of June the whole crop was well on its way and the world around us was so green that it seemed impossible that it could ever have been otherwise. By July, the sweating leaves of all of these plants had pumped the air so full of moisture that the humidity caused the electrical lines to buzz and crackle overhead.

My strongest memory of our garden is not how it smelled, or even looked, but how it sounded. It might strike you as fantastic, but you really can hear plants growing in the Midwest. At its peak, sweet corn grows a whole inch every single day and as the layers of husk shift slightly to accommodate this expansion, you can hear it as a low continuous rustle if you stand inside the rows of a corn field on a perfectly still August day. As we dug in our garden, I listened to the lazy buzzing of bees as they staggered drunkenly from flower to flower, the petty, sniping chirps of the cardinals remarking upon our bird feeder, the scraping of our trowels through the dirt, and the authoritative whistle of the factory, blown each day at noon.

My mother believed that there was a right way and a wrong way to do everything, and that doing it wrong meant doing it over, preferably a few times. She knew how to stitch a different tension into each of the buttons on a shirt, based on how often it would be called into use. She knew the best way to pick elderberries on a Monday such that their stems wouldn’t clog the old tin colander on Wednesday, when we strained them after stewing them all day Tuesday. Thinking two steps ahead in every conceivable direction, she never doubted herself, and I figured that there was nothing in the world she didn’t know how to do.

Whenever I looked at my mother, it was difficult for me to believe that the well-spoken and smartly dressed woman before me could ever have been a dirty, hungry, and scared child. Only her hands gave her away: They were far too durable for the life she now led, and I sensed that she could have grabbed the rabbit that plagued our garden and wrung its neck without thinking, had it been stupid enough to get too close to her.

When you grow up around people who don’t speak very much, what they do say to you is indelible. As a child, my mother had been both the poorest and the smartest girl in Mower County. During her senior year of high school, she was awarded an honorable mention in the ninth annual nationwide Westinghouse Science Talent Search. This was an unusual recognition for a female growing up in a rural area, and although it counted only as a near miss for the real prize, it put her in good company. Other 1950 also-rans included Sheldon Glashow, who went on to win a Nobel Prize in Physics, and Paul Cohen, who won the Fields Medal in 1966—the highest honor given in the field of mathematics.

Unfortunately for my mother, scoring an honorable mention carried with it a one-year honorary junior membership to the Minnesota Academy of Science, not the college scholarship that she had been hoping for. Undeterred, she moved to Minneapolis anyway and tried to support herself while studying chemistry at the University of Minnesota, but soon came to the realization that she couldn’t attend the long afternoon laboratory sections and still put in enough babysitting hours to pay her tuition. In 1951, the university experience was designed for men, usually men with money, or at the very least men who had job options outside of being some family’s live-in nanny. She moved back to our hometown, married my father, gave birth to four children, and threw herself into 20 years of raising them. Determined to earn her bachelor’s degree once the last of her children was at least in preschool, she re-enrolled in the University of Minnesota. Her options were limited to correspondence courses, so she chose English literature. Because I spent my days mostly in her care, it became natural for her to include me in her studies.

We plowed through Chaucer, and I learned to assist her using the Middle English dictionary. One year we spent the winter painstakingly noting each instance of symbolism within Pilgrim’s Progress on separate recipe cards, and I was delighted to see our pile grow to be thicker than the book itself. She set her hair in curlers while listening to records of Carl Sandburg’s poems over and over, and instructed me on how to hear the words differently each time. After discovering Susan Sontag, she explained to me that even meaning itself is a constructed concept, and I learned how to nod and pretend to understand.

My mother taught me that reading is a kind of work, and that every paragraph merits exertion, and in this way, I learned how to absorb difficult books. Soon after I went to kindergarten, however, I learned that reading difficult books also brings trouble. I was punished for reading ahead of the class, for being unwilling to speak and act “nicely.” I didn’t know why I simultaneously feared and adored my female teachers, but I did know that I needed their attention, positive or negative, at all times. Tiny but determined, I navigated the confusing and unstable path of being what you are while knowing that it’s more than people want to see.

When I was 5 I came to understand that I was not a boy. I still wasn’t sure what I was, but it became clear that whatever I was, it was less than a boy. I saw that my brothers, who were five, 10, and 15 years older than me, could do all of our laboratory play in the outside world. In Cub Scouts they raced model cars and built and set off rockets. In shop class they used tools big and powerful enough to be mounted on the wall or suspended from the ceiling. When we watched Carl Sagan and Mr. Spock and Doctor Who and the Professor, we never even commented on Nurse Chapel or Mary Ann in the background. I retreated further into my father’s laboratory, as the place where I could most freely explore the mechanical world.

It made sense, in a way. I was the one who was like our father, or at least I thought so. The differences between us were purely cosmetic: My father looked just like a scientist was supposed to. He was tall and pale and clean-shaven, thin-almost-gaunt in his khakis and white shirt and horn-rimmed glasses, complete with a pronounced Adam’s apple. When I was 5 I also decided that the real me looked exactly like that, even though on the outside I was disguised as a girl.

While pretending to be a girl I spent my time deftly grooming myself and gossiping with my girlfriends about who liked whom and what if they didn’t. I could jump rope for hours and sew my own clothes and make anything anybody wanted to eat from scratch in three different ways. But in the late evenings I would accompany my dad to his laboratory, when the building was empty but well lit. There I transformed from a girl into a scientist, just like Peter Parker becoming Spider-Man, only kind of backward.

As much as I desperately wanted to be like my father, I knew that I was meant to be an extension of my indestructible mother: a do-over to make real the life that she deserved and should have had. I left high school a year early to take a scholarship at the University of Minnesota—the same school that my mother, my father, and all of my brothers had attended.

My lab is a place where it’s just as well that I can’t sleep, because there are so many things to do in the world.

I started out studying literature, but soon discovered that science was where I actually belonged. The contrast made it all the clearer: In science classes we did things instead of just sitting around talking about things. We worked with our hands and there were concrete and almost daily payoffs. Our laboratory experiments were predesigned to work perfectly and elegantly every time, and the more of them that you did, the bigger the machines and the more exotic were the chemicals that they let you use.

Science lectures dealt with social problems that still could be solved, not defunct political systems for which both the proponents and the opponents had died before my birth. Science didn’t talk about books that had been written to analyze other books that had originally been written as retellings of ancient books; it talked about what was happening now and of a future that might yet be. The very attributes that rendered me a nuisance to all of my previous teachers—my inability to let things go coupled with my tendency to overdo everything—were exactly what my science professors liked to see. They accepted me despite the fact that I was just a girl, and assured me of what I already suspected: that my true potential had more to do with my willingness to struggle than with my past and present circumstances. Once again I was safe in my father’s laboratory, allowed to play with all of the toys for as long as I wanted.

People are like plants: They grow toward the light. I chose science because science gave me what I needed—a home as defined in the most literal sense: a safe place to be.

Growing up is a long and painful process for everyone, and the only thing I ever knew for certain was that someday I would have my own laboratory because my father had one. In our tiny town, my father wasn’t a scientist, he was the scientist, and being a scientist wasn’t his job, it was his identity. My desire to become a scientist was founded upon a deep instinct and nothing more; I never heard a single story about a living female scientist, never met one or even saw one on television.

As a female scientist I am still unusual, but in my heart I was never anything else. Over the years I have built three laboratories from scratch, given warmth and life to three empty rooms, each one bigger and better than the last. My current laboratory is almost perfect—located in balmy Honolulu and housed within a magnificent building that is frequently crowned by rainbows and surrounded by hibiscus flowers in constant bloom—but somehow I know that I will never stop building and wanting more. My laboratory is not “room T309,” as stated on my university’s blueprints; it is “the Jahren Laboratory” and it always will be, no matter where it is located. It bears my name because it is my home.

My laboratory is a place where the lights are always on. My laboratory has no windows, but it needs none. It is self-contained. It is its own world. My lab is both private and familiar, populated by a small number of people who know one another well. My lab is the place where I put my brain out on my fingers and I do things. My lab is a place where I move. I stand, walk, sit, fetch, carry, climb, and crawl. My lab is a place where it’s just as well that I can’t sleep, because there are so many things to do in the world besides that. My lab is a place where it matters if I get hurt. There are warnings and rules designed to protect me. I wear gloves, glasses, and closed-toed shoes to shield myself against disastrous mistakes. In my lab, whatever I need is greatly outbalanced by what I have. The drawers are packed full with items that might come in handy. Every object in my lab—no matter how small or misshapen—exists for a reason, even if its purpose has not yet been found.

My lab is a place where my guilt over what I haven’t done is supplanted by all of the things that I am getting done. My uncalled parents, unpaid credit cards, unwashed dishes, and unshaved legs pale in comparison to the noble breakthrough under pursuit. My lab is a place where I can be the child that I still am. It is the place where I play with my best friend. I can laugh in my lab and be ridiculous. I can work all night to analyze a rock that’s 100 million years old, because I need to know what it’s made of before morning. All the baffling things that arrived unwelcome with adulthood—tax returns and car insurance and Pap smears—none of them matter when I am in the lab. There is no phone and so it doesn’t hurt when someone doesn’t call me. The door is locked and I know everyone who has a key. Because the outside world cannot come into the lab, the lab has become the place where I can be the real me.

My laboratory is like a church because it is where I figure out what I believe. The machines drone a gathering hymn as I enter. I know whom I’ll probably see, and I know how they’ll probably act. I know there’ll be silence; I know there’ll be music, a time to greet my friends, and a time to leave others to their contemplation. There are rituals that I follow, some I understand and some I don’t. Elevated to my best self, I strive to do each task correctly. My lab is a place to go on sacred days, as is a church. On holidays, when the rest of the world is closed, my lab is open. My lab is a refuge and an asylum. It is my retreat from the professional battlefield; it is the place where I coolly examine my wounds and repair my armor. And, just like church, because I grew up in it, it is not something from which I can ever really walk away.

My laboratory is a place where I write. I have become proficient at producing a rare species of prose capable of distilling 10 years of work by five people into six published pages, written in a language that very few people can read and that no one ever speaks. This writing relates the details of my work with the precision of a laser scalpel, but its streamlined beauty is a type of artifice, a size-zero mannequin designed to showcase the glory of a dress that would be much less perfect on any real person. My papers do not display the footnotes that they have earned, the table of data that required painstaking months to redo when a graduate student quit, sneering on her way out that she didn’t want a life like mine. The paragraph that took five hours to write while riding on a plane, stunned with grief, flying to a funeral that I couldn’t believe was happening. The early draft that my toddler covered in crayon and applesauce while it was still warm from the printer.

Working in a lab for 20 years has left me with two stories: the one that I have to write, and the one that I want to.

Although my publications contain meticulous details of the plants that did grow, the runs that went smoothly, and the data that materialized, they perpetrate a disrespectful amnesia against the entire gardens that rotted in fungus and dismay, the electrical signals that refused to stabilize, and the printer ink cartridges that we secured late at night through nefarious means. I know damn well that if there had been a way to get to success without traveling through disaster someone would have already done it and thus rendered the experiments unnecessary, but there’s still no journal where I can tell the story of how my science is done with both the heart and the hands.

Eventually 8 a.m. rolls around, the chemicals need to be restocked, the paychecks need to be cut, the plane tickets need to be bought, and so I’ve lowered my head and written yet another scientific report while the pain, pride, regret, fear, love, and longing have built up deep in my throat unspoken. Working in a lab for 20 years has left me with two stories: the one that I have to write, and the one that I want to.

Science is an institution so singularly convinced of its own value that it cannot bear to throw anything away. This is true even of my father and his slide rules, carefully boxed in the basement of my childhood home and labeled “Standard Linear Slide Rule [25 cm] 30 ct.” There are 30 of them, because it is important that each student has his own—scientists do many things, but they do not share equipment. These old slide rules will never be useful again; they’ve been thoroughly and terminally outmoded, first by calculators, then by desktop computers, and recently by phones. Nobody’s name is written on the box, just a label itemizing what’s inside. I used to look at it and wish, with an inexplicable yearning, that my father would write my name on the box. But no one owns those slide rules; they just are. And they certainly never belonged to me.

Hope Jahren has received three Fulbright Awards in geobiology and is one of four scientists, and the only woman, to have been awarded both of the Young Investigator Medals given in the earth sciences. Named by Popular Science in 2005 as one of the “Brilliant 10” young scientists, she has taught and pursued independent research at universities around the country, most recently as a tenured professor at the University of Hawai’i at Manoa in Honolulu.

From the Book:

Lab Girl by Hope JahrenCopyright © 2016 by Hope Jahren

Published by arrangement with Alfred A. Knopf, an imprint of The Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House LLC.