A recent newcomer at one of the home-education groups my family attends explained that one of the frustrations that led her to take her son out of the school system was that he wasn’t being allowed to write stories. It’s something he loves to do, and it seems strange that a school should obstruct that enthusiasm. But the teachers declared he wasn’t ready because he can’t yet write in cursive.

To me this symbolizes all that is wrong with the strange obsession shared in many countries about how children learn to write. Often we teach them how to form letters based on the ones they see in their earliest reading books. And then we tell them that they must learn this hard-won skill all over again, using “joined-up” script. Yet there is no evidence that cursive has any benefits over other handwriting styles, such as manuscript, where the letters aren’t joined, for the majority of children with normal development.

I should make it clear I’m not referring to handwriting itself, often seen as synonymous with cursive. There is ample evidence that writing by hand aids cognition in ways that typing does not: It’s well worth teaching. And I confess I’m old-fashioned enough to think that, regardless of proven cognitive benefits, a good handwriting style is an important and valuable skill, not only when your laptop batteries run out but as an expression of personality and character. I should also say that cursive is a perfectly respectable, and occasionally lovely, style of writing, and children should have the opportunity to learn it if they have the time and inclination. My eldest child loves cursive and has the most elegant handwriting, in which I take great pride. And I love a good Victorian copperplate as much as anyone.

But imposing cursive from an early age is another matter. There should be a sound reason for it, as there should be reasons for teaching anything to children. Yet the grip that cursive exerts on much of teaching practice is sustained only by a disturbing blend of traditionalism, institutional inertia, folklore, prejudice, and bribery. It suggests that what teachers “know” about how children learn is sometimes more a product of the culture in which they’re immersed than a result of research and data. It seems unlikely, in this regard, that teaching cursive is unique in educational practice. Which forces us to wonder: What happened to evidence?

Something like modern cursive emerged from Renaissance Italy, perhaps partly because lifting a delicate quill off and on the paper was apt to damage it and spatter ink. By the 19th century cursive handwriting was considered a mark of good education and character. Teaching of manuscript lettering (not joined up) only began in the United States in the 1920s, to some controversy. In many countries today, including the U.S. and Canada, children are generally taught to write in manuscript in the first grade and are then taught cursive from second or third grade. In France, children are expected to use it as soon as they start to write in kindergarten, but in Mexico only manuscript is taught. The U.S. and United Kingdom leave some discretion for when cursive is taught, but there is the assumption that it will become the pupil’s normal mode of writing. When cursive is taught, it may become compulsory, so children may be marked down if they don’t write this way. In France, the cursive form is virtually universal and highly standardized, and children are discouraged from developing their own handwriting style.

Despite this diversity, the teaching of cursive is often accompanied by a strong sense of propriety. It’s simply the right thing to do. If you ask teachers why (I’ve tried), they’ll probably look at you oddly before offering a variety of answers, which will probably include these:

• It’s faster.

• It helps with spelling.

• It helps with dyslexia.

What does research say on these issues? It has consistently failed to find any real advantage of cursive over other forms of handwriting. “There is no conclusive evidence that there is a benefit for learning cursive for a child’s cognitive development,” says Karin Harman James, an associate professor in the Department of Psychological and Brain Sciences at Indiana University, who studies early brain development as a function of learning experiences.

James cautions that the issue is difficult to study because it’s hard to find children whose educational situation differs only in the style of handwriting. What’s more, a lot of the “evidence” that does get quoted is rather old and of questionable quality, and some of the findings are contradictory. Simply put, our real understanding of how children respond to different writing styles is surprisingly patchy and woefully inadequate.

The grip that cursive has on teaching is sustained by folklore and prejudice.

Let’s take a closer look, though, at what we do know. Many people (including teachers) swear that cursive is faster, and cite not only the fact that there is less lifting of pen from paper but also their own experience. Needless to say, the latter point is like me saying that English is a faster language than French because I can speak and read it more quickly. Of course that’s true for something you’ve done all your life.

Tests on writing speed have been fairly inconclusive in the past. But one of the best and most recent was conducted in 2013 by Florence Bara, now at the University of Toulouse in France, and Marie-France Morin of the University of Sherbrooke in Canada. They compared writing speeds for French-speaking primary pupils in their respective countries. While cursive is quite rigidly enforced in France, teachers in Canada are more free to decide which style to teach, and when. Some Canadians teach manuscript first and cursive later; some introduce cursive straight away in first grade.

So was cursive faster than manuscript? No, it was slower. But fastest of all was a personalized mixture of cursive and manuscript developed spontaneously by pupils around the fourth to fifth grade. Even in France, a quarter of the French pupils who were taught cursive exclusively and were still mostly using it in the fourth grade, had largely abandoned it for a mixed style by the fifth grade. They had apparently imbibed manuscript style from their reading experience (it more closely resembles print), even without being taught it explicitly.

While pupils writing in cursive were slower on average, their handwriting was also typically more legible than that of pupils taught only manuscript. But the mixed style allowed for greater speed with barely any deficit in legibility.

On the strength of these findings, Bara and Morin hesitated to make any recommendation for teaching a particular style except to say that it’s unwise to demand strict adherence to any of them—contrary to the French tradition. That idea is supported by Virginia Berninger, a professor of education psychology at the University of Washington. “Evidence supports teaching both formats of handwriting and then letting each student choose which works best for him or her,” she writes in a 2012 paper.

Does cursive help with writing and reading disorders such as dyslexia? There’s some evidence that it might. “Some children who have trouble printing letters do benefit from learning cursive because they do not have to take their pencil off of the paper as much,” says James. But, she adds, “these children are the exception, and the results cannot be generalized to all children learning to write.”

In fact, for typical children, there’s some reason to think manuscript has advantages. Because cursive writing is more challenging for motor coordination and for sheer complexity of the letters, some early research from the 1930s to the 1960s indicated that children develop their writing skills sooner and more legibly with manuscript. Because they have to lift pen from paper between each letter, children prepare better for the next letter. Some recent studies suggest that freeing up cognitive resources that are otherwise devoted to the challenge of simply making the more elaborate cursive forms on paper will leave children more articulate and accurate in what they write.

There’s also some suggestion that the difference in appearance between cursive and manuscript could inhibit the acquisition of reading skills, making it harder for children to transfer skills between learning to read and learning to write because they simply don’t see cursive in books. Reading and literacy expert Randall Wallace, of Missouri State University, says “it seems odd and perhaps distracting that early readers, just getting used to decoding manuscript, would be asked to learn another writing style.”

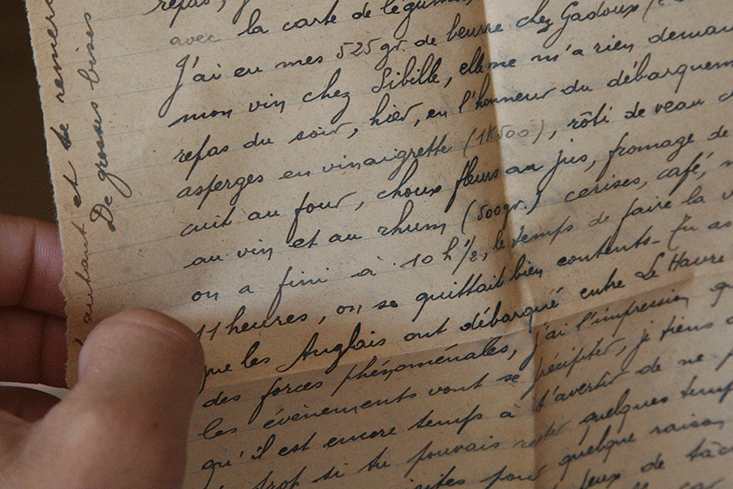

How many of us have great-grandmother’s letters in the attic, written in beautiful cursive?

It’s not clear, however, how much such difficulties truly show up. In a 2009 study in Quebec, Bara and Morin found no reading difficulties in primary-school children that correlated with learning cursive. Yet a more recent study by the pair and their colleagues, comparing Canadian and French primary schoolers, showed that those who learned only cursive handwriting performed more poorly than those who learned manuscript, or both styles, in recognizing and identifying the sound and name of individual letters.

Regardless of how significant or lasting these differences are, it makes sense that they should exist. There’s good evidence, both behavioral and neurological, that a “haptic” (touch-related) sense of letter shapes can aid early reading skills, indicating a cognitive interaction between motor production and visual recognition of letters. That’s one reason, incidentally, why it’s valuable to train children to write by hand at all, not just to use a keyboard.

But whether it makes any difference, in this regard, which form of handwriting is taught is less clear. In a brain-imaging study on older children, James says that she observed “no brain differences between the two styles of writing.” The type of handwriting doesn’t matter to such haptic feedback and reinforcement, she says, as long as children are creating the letter by hand and not tracing it.

In short, the jury is out over whether it is better to learn manuscript, cursive, or both forms of handwriting. There may be pros and cons in all cases. And even if being taught both styles might have some advantages, it’s not clear that those cognitive resources and classroom hours couldn’t be better deployed in other ways.

Why then do some educational systems place such importance on learning cursive? How, if not by consulting the evidence, are educational policy and teaching practices formed?

“My impression is that cursive is still taught primarily because of parental demand and tradition, rather than because there is any scientific basis for its superiority in learning,” says Wallace. What’s particularly troubling, though, is how inertia and preconceptions seem to distort perception and policy at the expense of the scientific evidence.

In 2011, Bara and Morin decided to take a close look at why teachers do what they do. They and their coworkers interviewed 45 primary-school teachers in Quebec and France about how and why they teach handwriting.

The results were sobering. Teachers had only sketchy knowledge, at best, of what research showed on the subject, especially when it came to the motor-function aspects of forming letters. Their views were, it seemed, formed primarily by the culture and institutional setting in which they worked.

While Canadian teachers were fairly mixed in their opinions about whether cursive was harder to learn than manuscript, and which should be taught when, French teachers were fairly unanimous. Four-fifths of them insisted that cursive was no more complex than manuscript, and three-quarters said that cursive is faster—a belief contradicted by Bara and Morin’s studies. More than half of the Quebec teachers thought that learning manuscript first assists learning to read, while only 10 percent of French teachers thought so.

In other words, teachers who are recommended by their education ministry to teach cursive, as in France, seem to become convinced that there are sound reasons for doing so, despite the lack of evidence. And teachers in Canada who decide for themselves to introduce cursive as soon as possible seem likewise to believe that there are advantages that justify this decision.

How much else in education is determined by what’s “right,” rather than what’s supported by evidence?

Just because the French situation is probably one of the least sinister or harmful examples of state brainwashing doesn’t mean we should shy away from calling it by its real name. Even in the more relaxed teaching practices in Quebec there’s a clear sign of the well attested psychological phenomenon in which we “find” evidence to support the decision we have already made anyway, and apply less rigorous judgment when our preconceptions are apparently confirmed.

Indeed, the way rational argument on the question of cursive handwriting so often evaporates suggests that there’s some kind of deep emotional investment at stake. When I wrote previously for a British magazine challenging the hegemony of cursive, it received one of the biggest responses the magazine had experienced. Here are just a couple of the popular defenses offered for cursive:

Imagine the frustration your kids will feel when they discover great-grandmother’s letters in the attic and can’t read them! Without cursive, you’re divorcing them from the past.

Cursive is beautiful, whereas manuscript looks childish.

But cursive is not another language. If you need to learn to read it, that takes an hour at most. Besides, how many of us have great-grandmother’s letters in the attic, written in beautiful cursive? (In the U.S. there are even suggestions that learning cursive is somehow patriotic and that without it people would not be able to read the Declaration of Independence.) And while I relish the elegance of Jane Austen’s original manuscripts, it’s plain that many people’s cursive is rather far from lovely, or indeed from legible. Manuscript, meanwhile, is only as childish as you decree it to be.

Beliefs about cursive are something of a hydra: You cut off one head, and another sprouts. These beliefs propagate through both the popular and the scientific literature, in a strange mixture of uncritical reporting and outright invention, which depends on myths often impossible to track to a reliable source.

Take a 2014 article in The New York Times about the pros and cons of handwriting. This alluded to a 2012 study allegedly demonstrating that cursive may benefit children with developmental dysgraphia—motor-control difficulties in forming letters—and that it may aid in preventing the reversal and inversion of letters. It’s a common claim, and so I began to delve into it.

I was taken to a paper by education researcher Diane Montgomery, describing a study that used an approach called the Cognitive Process Strategies for Spelling (CPSS) to try to help pupils with spelling difficulties, generally diagnosed as dyslexic. This method involves teaching these children cursive, with no comparison to other handwriting styles.

Cursive was chosen for use with CPSS, says Montgomery, because “experiments in teaching cursive … have proved highly successful in achieving writing targets earlier and for a larger number of children.” In support of that claim she cites two studies in journals from the early 1990s so obscure that even the British Library doesn’t stock them, but which were in any case conducted on non-dyslexic cohorts and so say nothing about benefits for dyslexics.

Montgomery writes that other dyslexia remediation projects have used cursive too, but cites only one “proven” advantage: a 1998 study allegedly reporting that “cursive script appeared to facilitate writing speed.” Not only is this claim contradicted by Bara and Morin’s work, but the 1998 paper doesn’t even make it. It simply reports how, for children taught a new cursive style in Australian schools, faster writing slightly decreases legibility.

Montgomery also cites a 1976 paper that allegedly advocates “the exclusive use of cursive from the beginning.” Except that it doesn’t do that at all. It describes a study comparing letter reversals and transpositions for 21 children at one school, taught cursive from the outset, with 27 from another taught first manuscript and then cursive. The first set showed slightly fewer of these mistakes, but the author acknowledged that, given the tiny sample size, “we in no way wish to offer the present data as documenting proof of the superiority of cursive over manuscript writing.”

So there we have it. But how many people will now be convinced that the benefits of cursive have been affirmed by The New York Times, based on the findings of academic research? No wonder teachers are confused.

Is there, then, any scientific case for making cursive writing a standard component of the primary curriculum? Wallace thinks not. Given the unproven benefits and the demands it places on time and effort, he feels that “the reasons to reject cursive handwriting as a formal part of the curriculum far outweigh the reasons to keep it.”

Others, like Bara, Berninger, and James, are more ambivalent, but find no evidence that cursive is best. Some feel that in certain respects it is worse than manuscript—it is slower, and time is wasted in learning (or sometimes relearning) this difficult skill. On the other hand, pupils differ, and there’s some potential value in giving them the option of finding what style suits them best, as well as exposure to different fonts so that they might generalize their letter-recognition skills. Or perhaps we should trust that children will find their own “hand” naturally, developing shortcuts for speed and so forth without having to be taught these in some rigid, formal, and standardized fashion.

There’s certainly a debate to be had. But it’s not one that seems to be taking place in schools or education ministries. And every time I hear of a young child turned off writing because he lacks the fine motor skills needed to master cursive, or prohibited from expressing herself freely because she’s not using the approved script, I see that our groundless obsession with cursive is not only pointless but can be destructive.

This must surely lead us to wonder how much else in education is determined by a belief in what is “right,” unsupported by evidence. Education and learning are difficult to pin down by research. Teaching practices vary, it’s often impossible to identify control groups, and socioeconomic factors play a role. But it’s often the case that the very lack of hard, objective evidence about an issue, especially in the social sciences, encourages a reliance on dogma instead. The danger is greater in education, which, like any issue connected to child rearing and development, is prone to emotive views.

All the same, there is some evidence. But it seems little heeded either by teachers or, more significantly, the policymakers who guide their practice. Too often, education is instead a political football. In 2013 in the U.K., the former Secretary of State for Education, conservative politician Michael Gove, became loathed by teachers for instituting changes to the national curriculum based on his own preconceptions about how and what children should learn. Gove’s notoriously dismissive attitude to specialist advice was made explicit in a recent interview, where he said that “people in this country have had enough of experts.” Such blithe disregard of research is not, needless to say, confined to the political right; education and learning are vulnerable to ideologies of all persuasions.

There needs to be wider examination of the extent to which evidence informs education. Do we heed it enough? Or is what children learn determined more by precedent and cultural or institutional norms? To judge from how children learn handwriting, the signs aren’t good.

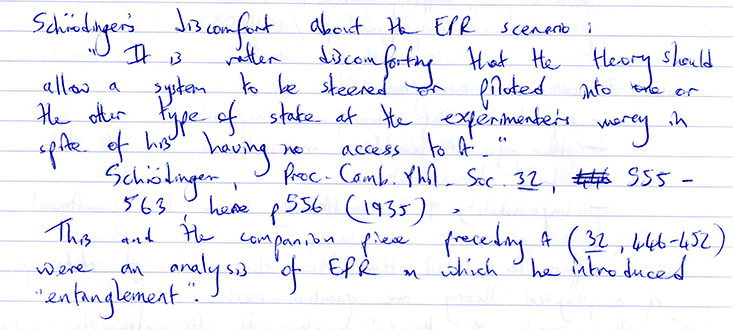

Philip Ball is a writer based in London. His latest book is The Water Kingdom: A Secret History of China. He is a left-hander who does not use cursive. As for what that does to his handwriting, he will let you be the judge: