Captain Picard: “How do we reason with them, let them know that we are not a threat?”

Guinan: “You don’t. At least, I’ve never known anyone who did.”

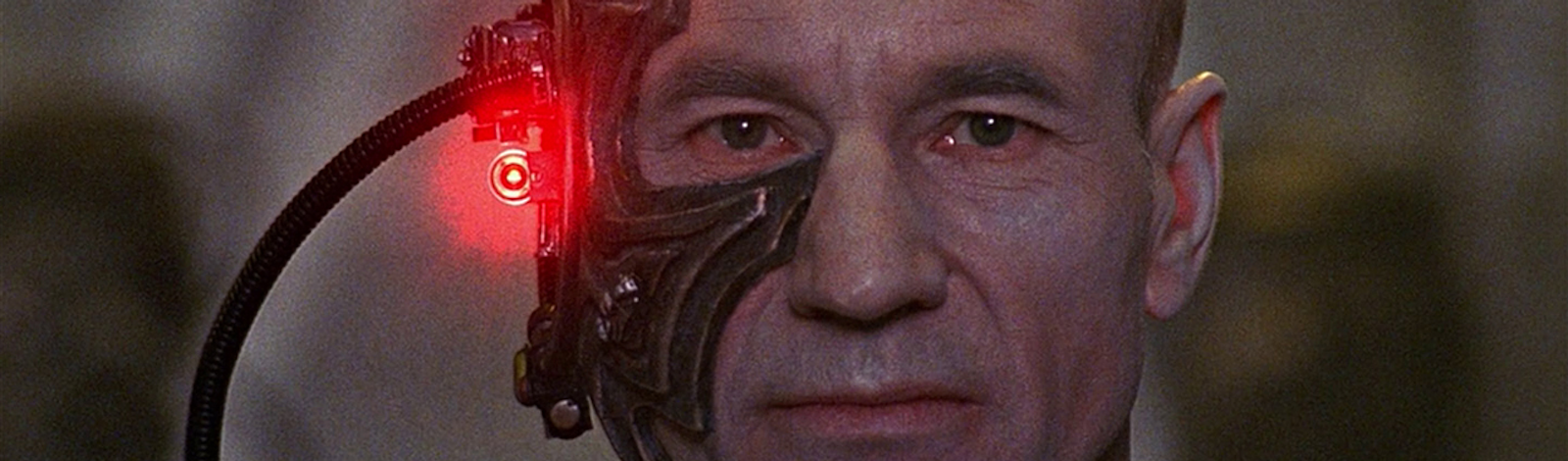

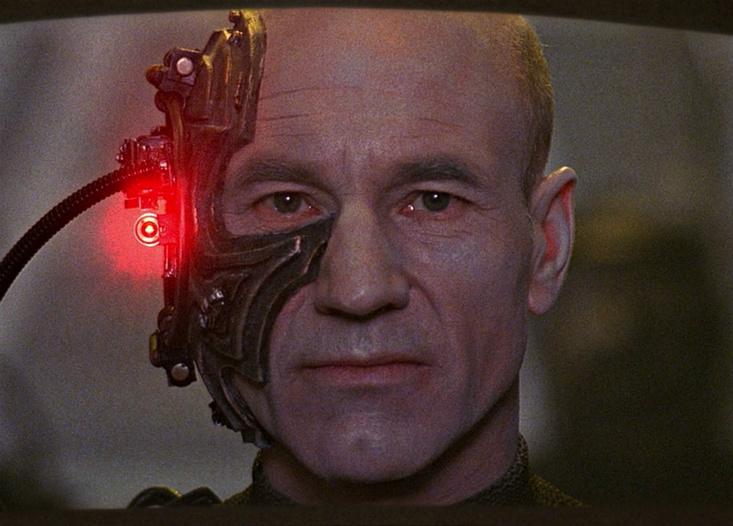

With this brief, ominous exchange, the heroes of Star Trek: The Next Generation are introduced to one of their most formidable enemies: the Borg, a race of cyborgs whose minds are linked to a collective “hive mind” through sophisticated technology. The collective expands their civilization through a process of mental and physical “assimilation”: They find new intelligent beings, like humans, implant them with Borg technology, and integrate them into the hive mind, erasing their previous identities.

Individual Borg are not conscious in the way humans are, and they have no sense of individuality. The hive mind is a dictator, an unquestioned voice that commands each individual. The Borg nature is split in two, an executive called the collective and a follower called the drone.

For the humans living in the Star Trek universe, the prospect of assimilation is terrifying. When asked why humans resist assimilation, Chief Engineer Geordi La Forge says, “For somebody like me, losing that sense of individuality is almost worse than dying.”

For many humans living in the real world, the fictional Borg are similarly unsettling. But why? What is it exactly about the Borg that irks us so? Could it be that somewhere in the recesses of our minds we sense something unpleasant about our ourselves when we view the Borg? What if they reflect a different kind of human mentality, one that was actually Borg-like?

The internal voices that commanded bicameral humans eventually fell silent, and humanity was forever changed.

An intriguing, albeit highly controversial, idea very much like this was actually proposed by Julian Jaynes, an American psychologist who taught at Princeton University. In his 1976 book, The Origin of Consciousness in the Breakdown of the Bicameral Mind, Jaynes theorizes that human consciousness—by which he means the ability and tendency to think about ourselves as individuals—emerged suddenly, and relatively recently in history, around 3,000 years ago. That would mean that anatomically modern humans were alive for hundreds of thousands of years before becoming conscious.

Jaynes argues that before this recent emergence of consciousness, humanity experienced the world in a manner similar to the Borg. There was not a holistic self with free will, but rather a two-part psyche, or “bicameral mind,” in which one part gave “orders” to a second part that acted on those orders. For bicameral humans, “volition came as a voice that was in the nature of a neurological command, in which the command and the action were not separated, in which to hear was to obey.” Jaynes says these commands were often perceived as coming from gods, and that they live on today as the internally hallucinated voices heard by some schizophrenics.

In this era, humans did not have an internal self that allowed for introspection or reflection. As such, the Borg are an excellent example of Jaynes’ description of the bicameral mind of early humans. The primary difference is that bicameral humans, unlike the Borg, were not technologically linked together in a single collective mind. Without collective thought, bicameral humans would have had trouble solving and managing complex problems. As ancient communities became more literate, urban, and complicated, Jaynes says the bicameral mind ”broke down,” a change that is reflected in the increasing consciousness of literary characters created soon after that time. After the advent of writing, the internal voices that commanded bicameral humans eventually fell silent, and humanity was forever changed.

But what about the Borg? Are they destined to remain nothing more than unconscious automatons for all Star Trek eternity? In a case of art imitating life (if in fact Jaynes’ theory is correct), it turns out it is possible for the Borg to undergo a transformation similar to the one undergone by bicameral humans. In the episode “I, Borg,” a single injured cyborg is captured and disconnected from the collective by the Enterprise crew. With the Borg executive silenced, this drone eventually becomes conscious and develops individuality, a close analog for Jaynes’ theory of the breakdown of the bicameral mind in humans. Before this transition, the isolated drone is unable to function, but afterward, it becomes endowed with a key feature of consciousness: the concept of “I.” In essence, this Borg—now named Hugh—attains human consciousness.

So maybe what we really fear is not the behavior of a fictional enemy, but a dark remnant of our historical selves. If Jaynes is correct, the transformation from internally commanded, unconscious beings to thinking, reflecting people would have to be considered the most significant and far-reaching adaptation in the history of our species. It was a change that gave us that which we are most loath to lose: our individuality.

Jacob Lopata is an entrepreneur, aerospace engineer, and commercial pilot based in Chicago.

This article originally appeared on our blog, Facts So Romantic, in November 2014.