The cellist Jan Vogler famously claimed that art is what makes us human. But what if machines start making art too?

Here’s an example of a piece of art made by an artificial intelligence (AI):

On the right side of the picture is a computer running an AI that has been trained with images of graffiti. It controls a plotting head that sprays water onto concrete blocks, on the left. The resulting patterns are a form of computer-generated art.

Is this fine art in the true sense? If it is, we would need to confront the possibility that some part of our humanity—the part that Vogler was referring to—has been captured by machines. The fact is, however, that while the output of the machine may be artistic, it is not making fine art.

When art is made to satisfy the needs of a third party—in this case, the computer programmer employed by the artist—it is illustration or commercial art, not fine art. If fine art is ever to be made by AI, it must be its own: produced by machines autonomously, independently, and actively for the machine’s own sake and with the machine’s own aesthetics. Only in that case would the art not be a passive product of human creation.

Will a true artificial artist ever exist?

On January 8 of this year, the Artificial Intelligence Art and Aesthetics Exhibition concluded its run at the Okinawa Institute of Science and Technology Graduate University (OIST) in Okinawa, Japan. The focus of the exhibition was this concept of true, artificially intelligent fine art. The only problem for the exhibitions curators (including myself) was that art in this category does not yet exist.

To get around this awkward fact, the exhibition shows were divided into four categories: (1) Human Art / Human Aesthetics, (2) Human Art / Machine Aesthetics, (3) Machine Art / Human Aesthetics, and (4) Machine Art / Machine Aesthetics. Category 1 contained a collection of conventional human art, from the Renaissance on. Categories 2 and 3 presented a collection of hybrid man-machine art, as their names imply. Category 4, on the other hand, had no machine-made art, because none exists that also reflects machine aesthetics. The category was a useful placeholder—and, as we’ll learn, it was not entirely empty.

Each category teaches us its own lessons. The art in Category 1 shows the historical transformation of aesthetics away from a God’s eye perspective, and toward a human perspective. The mostly 20th-century systemic art in Category 2, including minimalism, serial music, and visual poetry, is characterized by the use of rules or mathematical forms. Systemic art can be considered to have been kick-started by the Eiffel Tower in 1889. The tower’s construction was opposed by many famous artists, including the painter William Adolphe Bouguereau and the novelist Guy de Maupassant, because they viewed its plain appearance and machine-calculated design as a hideous denial of human aesthetics. The fact that the Eiffel Tower looks beautiful to most of us today is the central lesson of Category 2: Our aesthetic sense can be changed by mathematics and machines. Category 3 contains a kind of so-called media art, produced by machines and AI, showing us that even as a passive product of human creation modern AI is capable of producing objects of beauty.

Together, the first three categories of the exhibition describe an incomplete arc. We see the birth of the human author, and the beginnings of the AI author. But will a true artificial artist ever exist? Can we expect that aesthetics will one day be generated entirely from within the machine world, without any human-led design? This question was at the center of the exhibition: Will AI ever have its own aesthetic autonomy?

Plato argued that “the true, the good, and the beautiful” are all things that have value in themselves. Beauty has a value in its own right, not because it serves some other purpose. We do good for its own sake, and so on. In order for a machine to make its own fine art, it needs to satisfy Plato’s dictum, and create without any utilitarian purpose. The open question is whether machines will ever be able to do so.

One reason to be optimistic is that humans are not the only creatures capable of creation without utility. For example, given drawing materials, chimpanzees have been observed to produce drawings for the sheer pleasure of it. In fact, the Okinawa exhibition includes drawings by five chimpanzees and a bonobo owned by Tetsuro Matsuzawa, a professor at Kyoto University—and all are classified into Category (4), “Machine Art / Machine Aesthetics,” to remind us of what is possible. If the animals had produced drawings in return for bananas, we would not have included them in that category, because their art would not been created for its own sake.

For AI to get to where chimpanzees are, two steps are needed. First, AI must be able to generate its own goals. The goals of today’s AI are designed by human programmers, who write so-called evaluation functions to calculate how well or poorly an algorithm is doing at any given time. The first piece of machine-made art that qualifies for category 4 will need to be able to write its own evaluation functions.

Not only is this possible, it has already been achieved. In fact, if you visited our exhibition in Okinawa earlier this year, you could see it in action. Kenji Doya, a professor at OIST’s Neural Computation Unit, and his Smartphone Robot Development Team staged an experiment called “Can Robots Find Their Own Goals?” They placed a collection of robots made from smartphones on wheels into a common area. The robots were able to roam freely, find their own place to charge, and exchange programs by scanning each other’s QR codes. Charging was an analogue to eating, and exchanging programs an analogue to reproducing. Robots who didn’t charge stopped running, and those who did not exchange programs didn’t pass their “DNA” on to the following generation. Over time, the robots began to choose their own goals: Some stopped charging to chase other robots, for example, a behavior they were not programmed to exhibit. The results of this and other experiments have convinced Doya that robots can indeed make up their own goals.

When AI starts making fine art, will we recognize it?

The second step necessary for AI to produce fine art is that it be able to elevate secondary goals—those goals that exist only to serve its primary goal—into primary goals themselves. Suppose, for example, the primary goal of an organism or a machine is to breed. To have sex is a method to breed, so having sex is a sub-goal. To attract a partner is a method to have sex, which can be seen as a sub-sub-goal. To be beautiful is a method to attract a partner, which can be seen as a sub-sub-sub-goal, and so on. But for humans, sex and the beauty of a partner have gained value in their own right. Just as sex for sex’s sake can become valuable, so can art for art’s sake. When an AI has chosen its own goals, and then begun to pursue them for their own sake, it will be on the road to making its own fine art.

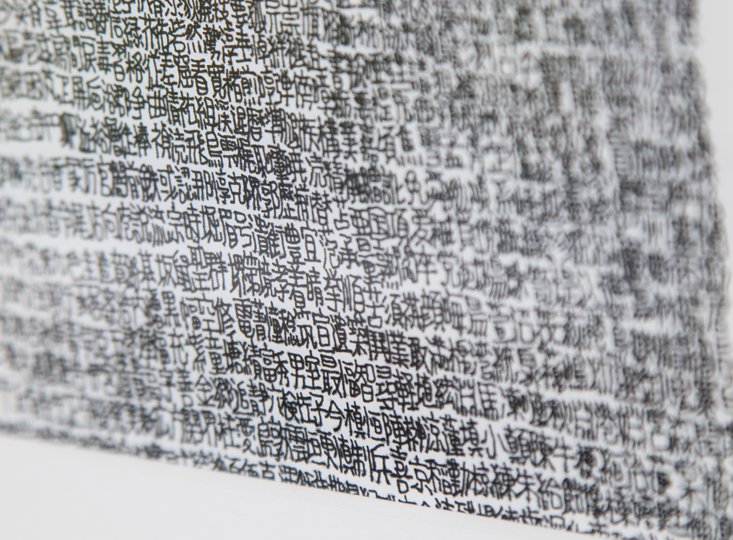

When AI starts making fine art, will we recognize it? We can teach AI our own art history as a way of encouraging output that we will recognize and enjoy. On the other hand, untrained AI will be more likely to produce something starkly original and even unrecognizable, after the manner of so-called Outsider Art or Art Brut. While we cannot divine the internal aesthetic sense of the autistic artist Moriya Kishaba, one of our category-2 exhibitors, many people find his tilings of tiny Chinese characters strangely beautiful. The future of AI art is analogous to a world full of artists like Moriya before they were discovered.

True AI fine art will be both painfully boring and highly stimulating, and that will be represent progress. Beauty, after all, cannot be quantified, and the very act of questioning the definition of aesthetics moves all art forward—something we’ve seen over and over again in the history of human-made art. The realization of AI will bring new dimensions to these questions. It will also be a triumph of materialism, further eroding the specialness of the human species and unveiling a world that has neither mystery nor God in which humans are merely machines made of inanimate materials. If we are right, it will also bring a new generation of artists, and with them, new Eiffel towers beyond our wildest imagination.

Hideki Nakazawa is a Japanese artist born in 1963. His activities include “Silly CG” in the 1990s, “Method Art” in the 2000s, and the publication of books including Art History: Japan 1945-2014. He is also a jury of Japan Media Arts Festival, and the representative and founder of Artificial Intelligence Art and Aesthetics Research Group.

Lead image photo collage credits: B.S.P.I. / Getty Images; vvoe / Shutterstock