Can you imagine a mind without language? More specifically, can you imagine your mind without language? Can you think, plan, or relate to other people if you lack words to help structure your experiences?

Many great thinkers have drawn a strong connection between language and the mind. Oscar Wilde called language “the parent, and not the child, of thought”; Ludwig Wittgenstein claimed that “the limits of my language mean the limits of my world”; and Bertrand Russell stated that the role of language is “to make possible thoughts which could not exist without it.”

After all, language is what makes us human, what lies at the root of our awareness, our intellect, our sense of self. Without it, we cannot plan, cannot communicate, cannot think. Or can we?

Imagine growing up without words. You live in a typical industrialized household, but you are somehow unable to learn the language of your parents. That means that you do not have access to education; you cannot properly communicate with your family other than through a set of idiosyncratic gestures; you never get properly exposed to abstract ideas such as “justice” or “global warming.” All you know comes from direct experience with the world.

It might seem that this scenario is purely hypothetical. There aren’t any cases of language deprivation in modern industrialized societies, right? It turns out there are. Many deaf children born into hearing families face exactly this issue. They cannot hear and, as a result, do not have access to their linguistic environment. Unless the parents learn sign language, the child’s language access will be delayed and, in some cases, missing completely.

Does our mind develop normally under such circumstances? Of course not. Language enables us to receive vast amounts of information we would have never acquired otherwise. The details of your parents’ wedding. The Declaration of Independence. The entrée section of the dinner menu. The entire richness of human experience condensed into a linear sequence of words. Take language away, and the amount of information you can acquire decreases dramatically.

The lack of language affects even functions that do not seem to be intrinsically “linguistic,” such as math. Developmental research shows that keeping track of exact numbers above four requires knowing the words for these numbers. Imagine trying to tell the difference between seven apples and eight apples. The task becomes almost impossible if you can’t count them—and you can’t count them if you never learn that “seven” is followed by “eight.” As a result of this language-number interdependency, many deaf children in industrialized societies fall behind in math, precisely because they did not learn to count early on.1

Without language, we cannot plan, cannot communicate, cannot think. Or can we?

Another part of your mind that needs language to develop properly is social cognition. Think about your interactions with your family and friends. Why is your mom upset? Why did your friend go inside the house just now? Understanding social situations requires inferring what the people around you are thinking.

This ability to infer another person’s thoughts is known as “theory of mind”; typically developing kids acquire this skill by age 5 or so. However, children with delayed language access have trouble imagining the mental state of other people.2 Moreover, brain regions involved in inferring others’ thoughts work differently in such children: They are active during all kinds of social situations, unable to properly distinguish scenarios that require mentalizing from those that do not.3 Theory of mind, therefore, is a prime example of a non-linguistic process that suffers if linguistic input is delayed.

So far, the evidence we have seen does suggest that “the limits of my language mean the limits of my world.” However, what happens if language disappears once the mind is fully developed? Will we then lose the ability to use math and understand others?

Imagine you are a typical adult; let’s say you’re 40. You wake up one day, and suddenly, you realize that your language is gone. You look around the room, but no words come to mind to describe the objects you see. You’re starting to plan out your day, but no half-formed phrases rush through your mind. You unlock your smartphone, but, instead of text, you see a sea of squiggles. Desperate, you cry out for help, and someone rushes up to you—but, instead of speech, all you hear is meaningless murmur.

The condition I have just described is known as global aphasia. It arises from severe damage to the brain, often as a result of a massive stroke. While some aphasias are temporary, in some cases the damage is irreparable, and the person may lose language for life. In your case, let’s say that a dozen doctors examined you and said (or, you think they said) that nothing can be done. If the limits of your language mean the limits of your world, should you conclude the way you experience the world is now fundamentally limited? Do you even have a mind?

Desperate, you attempt to figure out what cognitive functions you still have left. Can you count? 1, 2, 3 … You take a pen and write 5+7=12. You get a little bolder and attempt to multiply 12 by 5 in your mind, then 12 by 51 on paper. It works! Turns out, losing language as an adult does not prevent you from using math.

You meet up with some friends. You cannot understand a word they say, but you try to gesticulate—at least it’s an attempt at a conversation. You notice that they exchange guilty looks, then start discussing something in hushed voices (no need, since you don’t know what they’re saying anyway). You realize that they each thought the other one was going to bring a gift. You chuckle. Even though you can’t really communicate with your friends anymore, you still know what’s on their mind.

My experience of the world is not made less by lack of language but is essentially unchanged.

Research on adult individuals with aphasia has demonstrated that math, theory of mind, and many other cognitive abilities are independent from language.4 Patients with severe language impairments perform comparably to the rest of us when asked to complete arithmetic tasks, reason about people’s intentions, determine physical causes of actions, or decide whether a drawing depicts a real-life event. Some of them play chess in their spare time. Some even engage in creative tasks. Soviet composer Vissarion Shebalin continued to write music even after a stroke that left him severely aphasic.

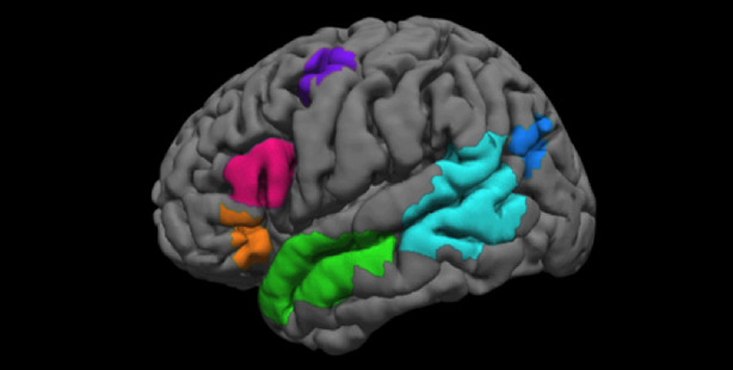

Neuroimaging evidence also supports the claim that language in adults is separate from the rest of cognition. In recent years, neuroscientists have isolated a network of brain regions (typically in the left hemisphere) that react almost exclusively to linguistic input.5 They respond to written sentences, spoken narratives, words, monologues, conversations, but will not activate in response to memory tasks, spatial reasoning, music, math, or social situations that do not involve dialogue. No wonder many patients with aphasia do not have impairments in other cognitive domains—language and other functions are housed in separate chunks of brain matter.

I have to admit, not all writers support Wittgenstein’s and Russell’s idea that language and thought are inseparable. Tom Lubbock, a British writer and illustrator whose language system gradually deteriorated because of a brain tumor, wrote in his memoir shortly before his death in 2011:

My language to describe things in the world is very small, limited. My thoughts when I look at the world are vast, limitless and normal, same as they ever were. My experience of the world is not made less by lack of language but is essentially unchanged.

So, what can we say about the role language plays in shaping our minds? Well, pick a mind that is still developing, and you will find that removing language will alter it for life. However, pick a mind that is fully formed and take all words away, and you will discover that the rest of cognition remains mostly intact. Our language is but a scaffold for our minds: indispensable during construction but not necessary for the building to remain in place.

Anna Ivanova is a Ph.D. student at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. She studies the neural basis of language and semantics under the wise guidance of Ev Fedorenko and Nancy Kanwisher. You can find her on Twitter as @neuranna.

References

1. Bull, R., et al. Numerical estimation in deaf and hearing adults. Learning and Individual Differences 21, 453-457 (2011).

2. Peterson, C.C. Empathy and theory of mind in deaf and hearing children. Journal of Deaf Studies and Deaf Education 21, 141-147 (2015).

3. Richardson, H., et al. Reduced neural selectivity for mental states in deaf children with delayed exposure to sign language. PsyArXiv, 10.31234/osf.io/j5ghw (2019).

4. Fedorenko, E., & Varley, R. Language and thought are not the same thing: evidence from neuroimaging and neurological patients. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1369, 132 (2016).

5. Fedorenko, E., Behr, M.K., & Kanwisher, N. Functional specificity for high-level linguistic processing in the human brain. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 108, 16428-16433 (2011).

Lead image: Juan Pablo Rada / Shutterstock