A provocative paper published on November 4, 2019 in the journal Nature Astronomy argues that the universe may curve around and close in on itself like a sphere, rather than lying flat like a sheet of paper as the standard theory of cosmology predicts. The authors reanalyzed a major cosmological data set and concluded that the data favors a closed universe with 99% certainty — even as other evidence suggests the universe is flat.

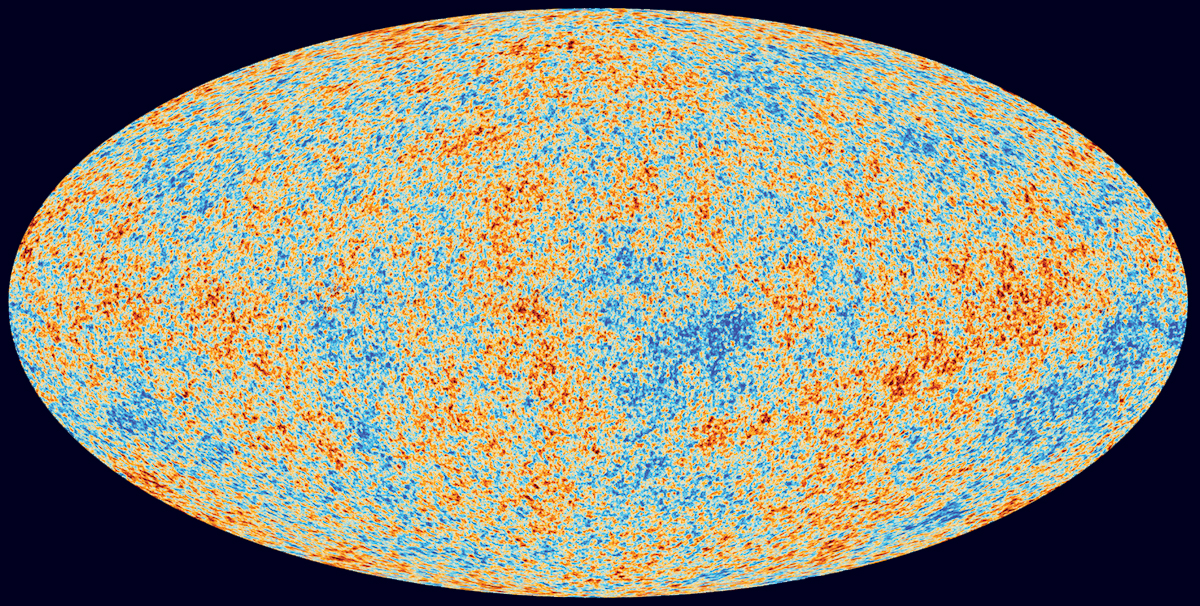

The data in question — the Planck space telescope’s observations of ancient light called the cosmic microwave background (CMB) — “clearly points towards a closed model,” said Alessandro Melchiorri of Sapienza University of Rome. He co-authored the November 4 paper with Eleonora di Valentino of the University of Manchester and Joseph Silk, principally of the University of Oxford. In their view, the discordance between the CMB data, which suggests the universe is closed, and other data pointing to flatness represents a “cosmological crisis” that calls for “drastic rethinking.”

However, the team of scientists behind the Planck telescope reached different conclusions in their 2018 analysis. Antony Lewis, a cosmologist at the University of Sussex and a member of the Planck team who worked on that analysis, said the simplest explanation for the specific feature in the CMB data that di Valentino, Melchiorri and Silk interpreted as evidence for a closed universe “is that it is just a statistical fluke.” Lewis and other experts say they’ve already closely scrutinized the issue, along with related puzzles in the data.

“There is no dispute that these symptoms exist at some level,” said Graeme Addison, a cosmologist at Johns Hopkins University who was not involved in the Planck analysis or Melchiorri’s research. “There is only disagreement as to the interpretation.”

Whether the universe is flat — that is, whether two light beams shooting side by side through space will stay parallel forever, rather than eventually crossing and swinging back around to where they started, as in a closed universe — critically depends on the universe’s density. If all the matter and energy in the universe, including dark matter and dark energy, adds up to exactly the concentration at which the energy of the outward expansion balances the energy of the inward gravitational pull, space will extend flatly in all directions.

The leading theory of the universe’s birth, known as cosmic inflation, yields pristine flatness. And various observations since the early 2000s have shown that our universe is very nearly flat and must therefore come within a hair of this critical density — which is calculated to be about 5.7 hydrogen atoms’ worth of stuff per cubic meter of space, much of it invisible.

The Planck telescope measures the density of the universe by gauging how much the CMB light has been deflected or “gravitationally lensed” while passing through the universe over the past 13.8 billion years. The more matter these CMB photons encounter on their journey to Earth, the more lensed they get, so that their direction no longer crisply reflects their starting point in the early universe. This shows up in the data as a blurring effect, which smooths out certain peaks and dips in the spatial pattern of the light. According to the new analysis, the large amount of lensing of the CMB suggests that the universe may be about 5% denser than the critical density, averaging something like six hydrogen atoms per cubic meter instead of 5.7, so that gravity wins and the cosmos closes in on itself.

The Planck scientists noticed the larger-than-expected lensing effect years ago; the anomaly showed up most prominently in their final analysis of the full data set, released last year. If the universe is flat, cosmologists expect a curvature measurement to fall within about one “standard deviation” of zero, due to random statistical fluctuations in the data. But both the Planck team and the authors of the November 4 paper found that the CMB data deviates by 3.4 standard deviations. Assuming that the universe is flat, this is a major fluke — about equivalent to getting heads in a coin toss 11 times in a row, which happens less than 1% of the time. The Planck team attributes the measurement to just such a fluke, or to some unaccounted-for effect that blurs the CMB light, mimicking the effect of extra matter.

Or perhaps the universe is really closed. Di Valentino and co-authors point out that a closed model resolves other anomalous findings in the CMB. For instance, researchers deduce the values of key ingredients of our universe, such as the amount of dark matter and dark energy, by measuring variations in the color of the CMB light coming from different regions of the sky. But curiously, they get different answers when they compare small regions of the sky and when they compare large regions. The authors point out that when you recalculate these values assuming a closed universe, they don’t differ.

Will Kinney, a cosmologist at the University at Buffalo in New York, called this bonus benefit of the closed universe model “really interesting.” But he noted that the discrepancies between small and large-scale variations seen in the CMB light could easily be statistical fluctuations themselves, or they might stem from the same unidentified error that may affect the lensing measurement.

There are only six of these key properties that shape the universe, according to the standard theory of cosmology, which is known as ΛCDM (named for dark energy, represented by the Greek letter Λ, or lambda, and cold dark matter). With only six numbers, ΛCDM accurately describes almost all features of the cosmos. And ΛCDM does not predict any curvature; it says the universe is flat.

“The point here is not that the universe is closed. The problem is the inconsistency between the data,” said Alessandro Melchiorri of Sapienza University of Rome.

The Melchiorri paper effectively argues that we may need to add a seventh parameter to ΛCDM: a number that describes the curvature of the universe. For the lensing measurement, adding a seventh number improves the fit with the data.

But other cosmologists argue that before taking an anomaly seriously enough to add a seventh parameter to the theory, we need to take into account all the other things that ΛCDM gets right. Sure, we can focus on this one anomaly — a coin coming up heads 11 times in a row — and say that something’s off. But the CMB is such a huge data set that it’s like flipping a coin hundreds or thousands of times. It’s not too hard to imagine that in doing so, we’ll encounter one random run of 11 heads. Physicists call this the “look elsewhere” effect.

Furthermore, researchers note that the seventh parameter isn’t needed for most other measurements. There’s a second way of gleaning the spatial curvature from the CMB, by measuring correlations between light from sets of four points in the sky; this “lensing reconstruction” measurement indicates that the universe is flat, with no seventh parameter needed. In addition, the BOSS survey’s independent observations of cosmological signals called baryon acoustic oscillations also point to flatness. Planck, in their 2018 analysis, combined their lensing measurement with these two other measurements and arrived at an overall value for the spatial curvature within one standard deviation of zero.

Di Valentino, Melchiorri and Silk think that pulling these three different data sets together masks the fact that the different data sets don’t actually agree. “The point here is not that the universe is closed,” Melchiorri said by email. “The problem is the inconsistency between the data. This indicates that there is currently no concordance model and that we are missing something.” In other words, ΛCDM is wrong or incomplete.

All other researchers consulted for this article think the weight of the evidence points to the universe being flat. “Given the other measurements,” Addison said, “the clearest interpretation of this behavior of the Planck data is that it’s a statistical fluctuation. Maybe it’s caused by some slight inaccuracy in the Planck analysis, or maybe it’s completely just noise fluctuations or random chance. But either way, there’s not really a reason to take this closed model seriously.”

That’s not to say pieces aren’t missing from the cosmological picture. ΛCDM seemingly predicts the wrong value for the current expansion rate of the universe, causing a controversy known as the Hubble constant problem. But assuming the universe is closed doesn’t fix this problem — in fact, adding curvature worsens the prediction of the expansion rate. Other than Planck’s anomalous lensing measurement, there’s no reason to think the universe is closed.

“Time will tell, but I am not, personally, terribly worried about this one,” Kinney said, referring to the suggestion of curvature in the CMB data. “It’s of a kind with similar anomalies that have proven to be vapor.”

Corrected on November 4, 2019: The original version of this article referred to the BOSS satellite. In fact, the BOSS survey was conducted on a ground-based telescope.

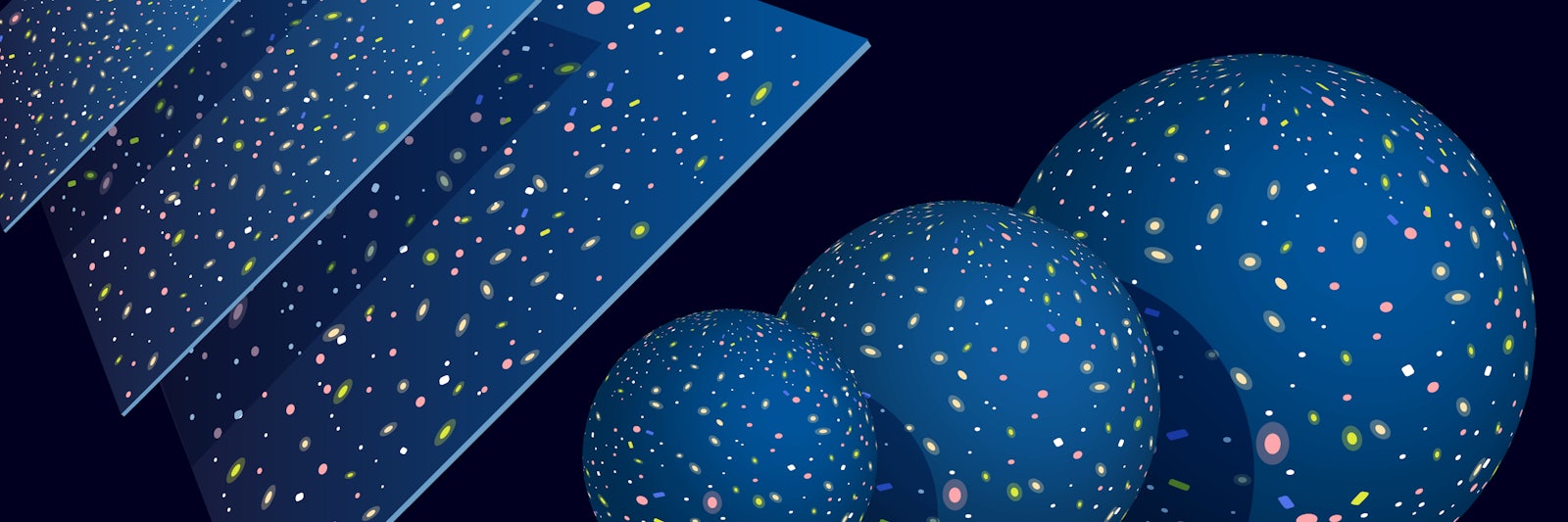

Lead image: In a flat universe, as seen on the left, a straight line will extend out to infinity. A closed universe, right, is curled up like the surface of a sphere. In it, a straight line will eventually return to its starting point. Credit: Lucy Reading-Ikkanda/Quanta Magazine