If you ask Siri to show you the weirdest people in the world, what images might you see? In fact, none. Siri showed me different links to the same scientific paper, published a decade ago, with the questioning title, “The weirdest people in the world?”

By some stroke of luck, or a divine favor from the science-communication gods, “weird” turns out to be an acronym for capturing the weirdness of people raised in Western, educated, industrialized, rich, and democratic societies. WEIRD people, like myself and many of you reading this, are, unfortunately, part of a problem that still faces psychology, a discipline largely dedicated to parsing what all humans share in common: The field’s research subjects are too damn weird. For too long, psychologists have focused their research on “one particular culture,” Michael Muthukrishna, an assistant professor of economic psychology at the London School of Economics, told me. “To be honest, it’s worse than that, because scientists were actually looking at a subset of that population, undergraduates, who aren’t representative of less educated populations within the country.”

Last month, a story in The Atlantic described how “The weirdest people in the world?” has made waves in the years since Joseph Henrich, now at Harvard University, wrote the paper with his colleagues. The WEIRD people problem is well documented—psychological findings based on Western populations don’t replicate in non-WEIRD populations—yet psychologists have yet to rectify this limitation. Muthukrishna, who did his doctoral dissertation under Henrich, said cross-cultural psychologists often still rely on online “convenience sampling” from around the world, yet participants are superficially diverse. The Atlantic called this “The Problem That Psychology Can’t Shake.”

To Muthukrishna, the problem isn’t so implacable. He’s the lead author of a paper, forthcoming in Psychological Science, co-authored with Henrich and others, titled, “Beyond WEIRD Psychology: Measuring and Mapping Scales of Cultural and Psychological Distance.” The researchers have come up with a way to quantify how close and far, culturally, societies are from one another. In particular, the paper illustrates how culturally distant countries are from the United States and China—two societies distinguished by their wealth of psychological data and their relatively strong cultural separation. This helped him make the point that “cultural psychology is not the difference between China and the U.S.—it’s the difference between societies all over the world,” Muthukrishna said. Measuring those differences, though, can seem like an “impossible task if you’re not doing it theoretically and systemically.”

In a conversation by Skype, Muthukrishna walked me through his findings, using his maps and figures, both from the paper and from his website, culturaldistance.com.

How do you explain cultural evolution?

What makes us a new kind of animal, and so different and successful as a species, is we rely heavily on social learning, to the point where socially acquired information is effectively a second line of inheritance, the first being our genes. Imagine something like a cyclical drought. You may have never experienced one, so you have no idea how to survive in one, and maybe even your parents haven’t, but say Grandma remembers that when she was a child, a drought came and everyone went to the mountain, past the forest, and they discovered water. So, she guides them to safety. These kinds of stories exist in the anthropological record.

That gets you to social learning, but dual-inheritance theory goes a little further and says, actually, that inheritance is itself an evolutionary system. It has variation. When people socially learn from each other, they often learn without understanding why what they’re copying—the beliefs and behaviors and technologies and know-how—works. People tend to home in on who seems to be the smartest or most successful person around, as well as what everybody seems to be doing—the majority of people have something worth learning. When you repeat this process over time, you can get, around the world, cultural packages—beliefs or behaviors or technology or other solutions—that are adapted to the local conditions. People have different psychologies, effectively. We almost speciated around cultural lines.

How do your cultural distance maps offer insight into the political situation going on between China and Hong Kong?

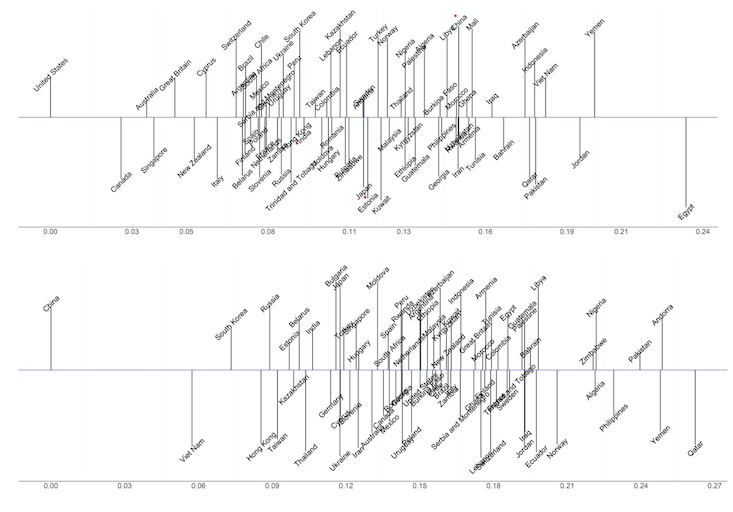

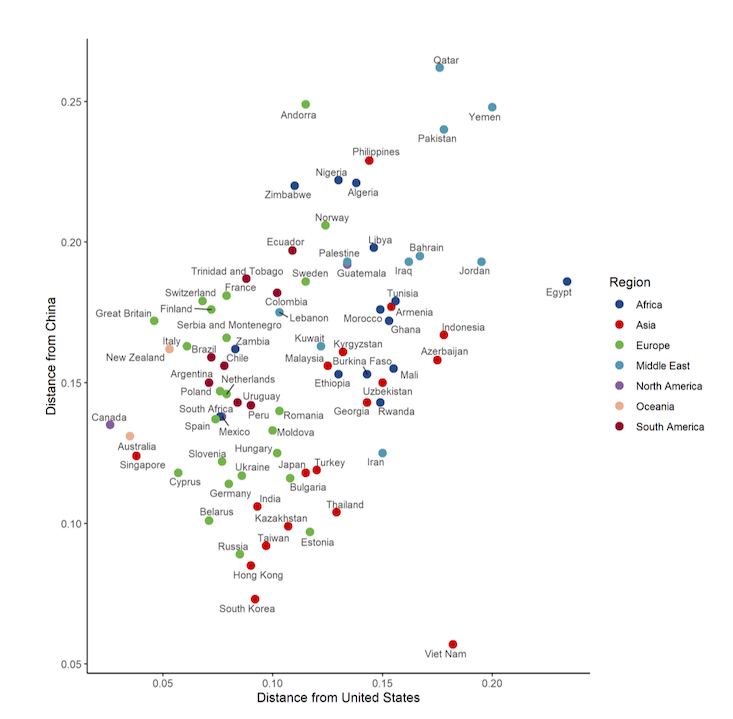

Hong Kong is fairly close to China, where you’ve got Vietnam and South Korea. But the distance from China to Hong Kong is something like the distance from the United States to Brazil, or the United States to Switzerland. It’s quite a distance.

Here’s what’s interesting: Hong Kong is also quite close to Great Britain. The distance between Great Britain and Hong Kong is not that different to the distance between China and Hong Kong. Hong Kong shares cultural features with China, but it also shares features with Great Britain, unsurprisingly given the 100-year history. There are naturally going to be cultural clashes between how you think Hong Kong should run. The people are Chinese, but they’re also British in some sense.

To what practical use could this cultural-distance map be put?

There’s military implications, corporate implications. Where do coalitions work out and where do they break down? I could see if cultural distance predicts past trade successes or failures. Some aspects of culture—pride, honesty, degree of liberal attitudes, value placed on authority—can impede trade communications or trade relationships. It’s under-explored. It’s something we’re looking at right now in my lab.

How do you measure cultural differences?

We apply a statistical technique used in genetics, called (FST), or the fixation index, not to a genome, but a culturome, or surveys of cultural beliefs and behaviors—in this case, the World Value Survey. So, in the genetics case, say you’re looking at the allele frequencies for eye color. If you have one population that’s entirely blue eyes and another population that’s entirely brown eyes, all of the variation between those populations is between groups. The between-group variation is equivalent to the total variation. When you divide the two, you’re going to get 1. That’s the maximum (FST), as different as any of the population can be. You could do this sort of analysis across all of the loci in a genome to figure out how genetically distant, for example, two fish populations are that live in two different ponds that, occasionally, becomes a single pond. We use the same math to look at a culturome. Instead of loci for eye color or hair type, we treat questions on the survey as loci.

What sort of traits are covered in the World Values Survey?

There’s politics, like attitudes toward democracy; social relationships, like how to raise children; religious norms and traditions; and attitudes toward sex, finances, law, environment, science and innovation, arts and creativity, sports and recreation, the media, and consumerism.

What do you get after applying that statistical technique to the culturome?

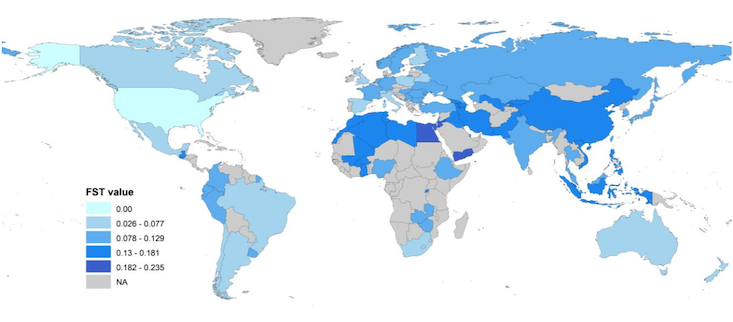

What you end up getting is this n-dimensional space of different loci. In other words, when societies differ from one another, they can differ along many different dimensions. Take this map, which depicts the American scale. It shows how culturally close you are to the U.S.

The deeper the blue, the more culturally distant you are. If you look at Canada and parts of South America, they’re not all that culturally distant. If you look at Europe, many places are quite culturally similar to the U.S. Whereas you look at, let’s say, North Africa and the Middle East—quite culturally different, and somewhere in between you have East Asia. But just because, on this map, Taiwan and Colombia are, culturally, similarly distant from the U.S., it doesn’t mean that they are culturally similar to one another.

The map is a visual representation of another figure, in which we’re cutting a line through that n-dimensional space and collapsing it down.

If you look at the U.S., Canada is culturally similar, as is Australia. If you look at China, Vietnam and South Korea are quite culturally similar. The point, though, is that the world, culturally, doesn’t go linearly from the U.S. to whatever the endpoint is—Egypt, in this case. Those countries in between the U.S. and Egypt are not similar to each other because they fall in between them. To see this, look at Figure 5, in which I draw distance from China and distance from the U.S. You can see that some countries are not close to either China or the U.S.

Being far culturally from the U.S. doesn’t mean being close to China.

Exactly. And if you look at a place like Qatar, Yemen, or Pakistan, it is not close to China, not close to the U.S.

Tell us what the numbers mean. On the map, the U.S. is zero, and the next blue shade is 0.02 to 0.077.

The one nice thing about (FST), or the fixation index, is that it meaningfully goes from zero to 1, in the same way that a correlation is meaningful from -1 to 1. The fact that the maximum score from the U.S. is no more than 0.25 means that you’re not in that situation I described earlier, where it’s all blue eyes and all brown eyes. In other words, most humans around the world have more in common with one another than they have differences. If they had more differences than they had in common, you would have scores above 0.5. The fact that our scores are basically bounded between zero and 0.3 tells you that the cultural distance between countries can be quite large, but not enormous to the point where we’re totally different.

It would be pretty insane, then, for another country to exist that was at around 0.7 cultural distance from the U.S.?

Yes, that would be like a cultural Galapagos. It would be a culture that didn’t love their children and, I don’t know, primarily had sex with animals. They’d spend all their time in the water, swimming. They would believe that children rule the society and not adults. It would be one of those fantasy worlds.

How do you end up with a cultural distance number between zero and 0.3 for particular countries?

We take the last two waves of the World Value Survey, from 2005 to 2015 and, within that scale, we look at all of the traits that, theory and some evidence suggests, should be culturally transmissible. Then we take the aggregate across all of the traits. You don’t have to capture everything—just a wide array of traits—because cultural evolutionary theory says that cultural traits should cluster within a society, meaning the things that I measure will be correlated with other aspects of the culture. As long as you do that, you’re going to have a fairly reliable scale. It is astonishing how robust this is. You can randomly toss out 60 percent of the questions, and the scale won’t deviate all that much.

What’s an example of cultural traits clustering?

One of my favorite examples of this is vaccinations and homeopathy. Homeopathy is basically about taking a little bit of something poisonous to make you better and stronger. Logically, that sounds a lot like a vaccination to me, a little bit of something bad makes you well, but even though there might be this tenuous logical connection, if you believe in homeopathy, you probably are also anti-vaccine.

Why do certain traits tend to cluster around each other?

That falls right out of cultural evolutionary theory. The reason that they cluster within a population is because of common sources of information. If you say, “I believe in evolution,” or, “I don’t believe in evolution,” it doesn’t really affect your life. I mean hell, if you say the Earth is flat, that doesn’t really affect your life. A lot of our beliefs are signaling our membership. They were acquired from who we consider to be successful or prestigious models, or copied by the majority of people within our social groups. So you can get this artificial clustering simply because the prestigious models are pushing idiosyncratic things.

How does this genetics-inspired method of culture measurement compare to others psychologists use?

Some people will take mean differences on dimensions that they think matter—individualism and collectivism, for example. And then they’ll say, for instance, “Ukraine is more individualistic than is China.” But what that really does is reduce a population to a point estimate. In reality, populations aren’t like that—they’re distributions. In the United States, there’s got to be people who are very collectivist, very family-oriented and people who are very individualist. Same in China.

How do you think about cultures that foster or facilitate anti-democratic tendencies like corruption?

People often think, “Why are some countries corrupt?” To me, that’s not the puzzle. The puzzle is: Why are some countries able to suppress corruption? The reason I frame it that way is because, from a cultural evolutionary perspective, corruption is what is natural to us. We cooperate with friends who we regularly interact with through direct reciprocity. You scratch my back, I scratch yours, I help you, you help me, screw me over, I screw you over. We rely on reputation, and so on. Corruption, I argue, is one scale of cooperation—a lower, more natural, more stable scale—undermining another. A president gives a contract to his daughter, and we say that’s nepotism. But really that’s inclusive fitness, undermining institutional punishment. If you give a job to a friend because they are your friend, that’s cronyism. But that’s also just direct or indirect reciprocity, undermining our meritocracy. So, if you’re a democracy, you need to be on the same page so that you’re only arguing at the margins. But if you are very regionally diverse to the point where people can coordinate as groups, then those groups will undermine the higher-order cooperation, like a democracy.

Has political culture in the U.S., to your eye, undergone any significant change?

Institutions rest on invisible cultural pillars. For example, it doesn’t matter what the Constitution says if you ignore it. If you don’t have a belief in the rule of law, then it doesn’t matter how good your legal systems are. They won’t get applied, which is what’s at stake in the recent political happenings in the U.S. It’s not just the institutions that are being challenged—it’s the norms. That, to me, is the real threat. Because lower-order scales of cooperation, like family and friends, are more stable, society is always at risk of slipping backward, not emphasizing higher-order scales of cooperation, like merit and rule of law and other institutions. To love your family, and to be there for your friends, is a very natural instinct. But you have to put limits on that. Every generation has to relearn those limits. Our Western institutions co-evolved with norms that supported them. That’s why they’re so difficult for economists to transport. If it were true that it was just institutions, Liberia would be one of the most successful countries on Earth, because it took a bunch of U.S. institutions. But it’s not, because the norms behind them are missing.

Is most of the world individualist or collectivist?

I think most of the world is collectivist. Places that are more collectivist are also more nepotistic. Those two things go hand-in-hand. Places filled with disease or lacking in material security, where governments failed to provide for their citizens, tend to be places where citizens have no choice but to rely on friends and family. You really need to be xenophobic, to keep outsiders away who can bring in disease. Doing things your own way is generally a recipe for harming your group. Individualism is on the rise, but it’s interesting to people because they realize that when they travel. They’re like, “Wow, you really care a lot about your family. Your family makes a lot of decisions for you.” It’s an obvious cross-cultural difference.

How did individualism arise in a mostly collectivist world?

Jonathan Schultz has a paper in Science where he argues that, in Europe, the banning of cousin marriage may have increased individualism. He tries to show a causal relationship. The Catholic Church decided that cousins were no longer allowed to marry each other in the way that they do pretty much everywhere in the world. That resulted in a breakdown of kin relations. If you marry people, normally you get more and more distant from one another, unless you start marrying your cousin. Then your uncle is also related to you. Most of the world operates that way. But you can breed more individualists when you don’t have these tight family connections as a result of that ban, which leads to other things, like being more mobile. You move into cities, you freely choose the occupation you want to take up. It’s a fairly recent phenomenon, but it’s probably spreading wide, especially with urbanization. In places higher in material security, you can afford to be a bit more individualistic. You need to suppress the incentives to be there for your family, to be there for your friends and to ignore the meritocracy.

This reminds me of The Irishman. The movie depicts how Mafia connections to the government, or connections among family and friends to the government, can play out badly.

Absolutely. You’ll start to see it everywhere. Once you have this perspective, it makes a lot of sense. When groups can coordinate with one another, they become powerful and can sometimes take down less coordinated groups.

Brian Gallagher is the editor of Facts So Romantic, the Nautilus blog. Follow him on Twitter @BSGallagher.

Lead image: Sun_Shine / Shutterstock