On an October day in 1849, a young writer packed up his notebooks, piled into a horse-drawn carriage, and left western Massachusetts for the outer edge of a sweep of sand known as Cape Cod. The writer was Henry David Thoreau, and over the next six years he would return here three times, forgoing the dappled shade of the woods that would make him famous in exchange for the Cape’s scrubby dune plants, empty beaches, and endless sky.

In his book Cape Cod, Thoreau would go on to describe miles of undomesticated coast at the mercy of the sea, stunning in its mercurial moods and stark beauty. Even 150 years later, despite an influx of tourists that would have startled the sun-bleached fishermen Thoreau met, many of the writer’s descriptions of the outer Cape feel strikingly familiar.

What does not is the way he writes of the Cape’s sharks.

In one of the book’s memorable passages, Thoreau writes of seeing a six-foot shark swim through an area where he and some friends had just been swimming. Despite being warned by locals, the group jumped back in, seemingly unperturbed. “We thought that the water was fuller of life,” Thoreau wrote, “and the expectation of encountering a shark did not subtract anything from its life-giving qualities.”

It’s a description that might have startled Barbara Stedman of Wellesley, who I met standing in the sand at Head of the Meadow Beach in Truro. She’d joined in on my conversation with a couple on a neighboring blanket, Tom and Jackie, when she heard mention of sharks. But when Tom noted that sharks could be found all along the Cape’s Atlantic shore as well as in Cape Cod Bay, she shuddered.

“Those creeps!” she said, her face opening with shock. “That gives me something to worry about. I thought I was relaxing.”

Stedman’s reaction seems far more typical on contemporary Cape Cod, and throughout much of the world, than the sanguine Thoreau’s. Over the last 15 years, the Cape has grappled with a steep rise in visits by great white sharks—Carcharodon carcharias, they of Jaws fame—who come to the outer Cape to hunt seals, often uncomfortably close to beaches. In 2018, fear ignited when two shark attacks left a swimmer gravely wounded and a young boogie-boarder dead.

What’s followed in the years since has been a feeding frenzy of a different kind, in which media attention descends on every shark sighting and beach closure on the Cape between May and November. That attention has also magnified those voices calling for measures more drastic than just closing beaches. A contingent of Cape Codders has advocated for killing sharks, or killing seals, in order to wrestle back control of these beaches.

As tragic as the events of 2018 were, I’ve always found this hysteria somewhat puzzling. After all, there are many places around the world, and even in the United States, that have more shark incidents and don’t get the same level of media coverage. According to the International Shark Attack File, Florida leads the pack in the number of unprovoked attacks annually, with 21 in 2019. Hawaii had nine in the same year, while California had three.

On top of that, modern science has largely debunked the idea of sharks as marauding “man eaters.” Most shark bites are a shark’s unfortunate way of figuring out what’s sharing their environment, or a case of mistaking humans for a seal. I’d believed that people were starting to come around on sharks, both as they grasped the nature of these accidents, and as a nascent “save the sharks” movement publicized how many sharks are killed by humans every year. Did people still really want to kill more of them?

Yet beyond the headlines, there was another story: one of ecosystems and communities in flux, and one that fits a pattern identified by social scientists in other “sharky” places. Research from around the world suggests that humans not only can live with our toothy neighbors, but that in many places, we’ve already started to. The fearful narrative we are all too familiar with doesn’t appear to be coming from communities themselves, but from the politics and news coverage that surrounds attacks.

The implications of that disparity stretch well beyond the sandy edges of tourists’ beach vacation. Sharks of all sizes are essential to the health of ocean ecosystems, but overfishing, climate change, and habitat destruction are winnowing their populations worldwide. With so many of these species sharing the shallow coastal waters we humans enjoy, how our species feels about sharks is integral to their survival.

In other words, saving sharks relies less on trying to change the shark’s ancient behaviors, and more on finding our inner Thoreau: in changing our own way of thinking about them.

How our species feels about sharks is integral to their survival.

Among the varied crowd of its year-round residents, Cape Cod has a long and much-argued tradition of distinguishing between those who were born here, and those who moved here. According to these unwritten rules, only those born on the peninsular side of the Cape Cod Canal get to wear the official title of “Cape Codder.” The rest of us are all “wash-ashores,” whether residents for one year or eighty years.

But how about 450 million?

That’s when the very first sharks arose, evolving around 200 million years before the dinosaurs and outliving them all. As scores of land species rose and fell, sharks swam cooly through asteroid strikes, five mass extinctions, five ice ages, and all of the dramatic global warming in between. When a glacier carved the arm of the Cape on its retreat northward, between 14,500 and 15,500 years ago, the modern great white shark had already been around for between six and eight million years.

All of that changed in the late 1800s, when the northeastern states of Maine and Massachusetts set off a seal-killing spree by paying bounties for seal pelts in a misguided attempt to protect local fisheries. By the time these bounties ended and the 1972 Marine Mammal Protection Act took effect, gray seals had been exterminated south of the Canadian border. Only a few hundred harbor seals remained in Massachusetts. One 2009 paper estimated that between 72,284 and 135,498 seals had been killed.

Around the same time, people stopped spotting great white sharks, also known simply as white sharks, as well. Some of this may have been because they moved further offshore, switching to fish and whales from seals. But the great white population itself also declined in the northwestern Atlantic through the 1970s and 1980s. Shark fishing was then unregulated, and a growing U.S.-China relationship built an American trade in shark fins and meat that still exists, albeit in a more sustainable form, today. Research suggests that the population decreased by as much as 86 percent over two decades, bottoming out around 1988.

And of course, you can’t talk about great white sharks without talking about Jaws. The 1975 movie inspired the creation of shark fishing tournaments worldwide, where thousands of fishermen headed in search of a trophy great white of their very own. The effect of this recreational fishery remains unquantified but is thought to have played a role in white shark declines.

Both commercial and recreational fishing for great whites was banned outright in 1997. Not long after, populations started to rebound, just as seal populations hit their stride again. Starting in the early 2000s, commercial vessels began reporting white sharks attacking fishing gear. Seals started showing up dead or injured on shore, missing large bits of themselves. People began seeing the attacks on seals firsthand, in bloody, thrashing spectacles not far from shore.

For ecologists, it was an incredible success story. Sharks of all sizes are a vital piece of natural ocean ecosystems, both as predator and prey. And while half of shark species are less than three feet long, larger sharks like great whites play an important regulatory role: they eat sick and injured fish, leaving the healthiest to reproduce, and prevent any one group from becoming overpopulated. Just their presence can shape an ecosystem; one 15-year study in Australia showed that with tiger sharks nearby, dugongs, dolphins, birds, and sea turtles chose to eat elsewhere, in turn influencing the distribution of keystone plants like seagrass.

Yet catch reports suggest global shark populations may have decreased by at least 20% worldwide just in the last two decades, with much more dramatic declines in some places—up to 99% for some species in the Mediterranean. An estimated one-third of all shark species are at risk of extinction. In such a world, the white sharks’ return to the north Atlantic signaled both that species conservation worked and that their ecosystem was healthy enough to support them.

However, experts knew it was only a matter of time before these returning sharks started interacting with humans. As unlikely as a shark bite is to an individual—statistics famously remind us that you’re much more likely to be struck by lightning, crushed by a vending machine, brained by a coconut, or mauled by your neighbor’s dog—Cape Cod had both a lot of seals and a lot of humans in the water.

The first came in 2012, when a white shark bit swimmer Chris Meyers in Truro. After a quiet spell, 2018 saw the attack on William Lytton, just ten miles south of the spot where I spoke to Barbara Stedman, and the death of Arthur Medici. To the community, this did not feel like a success story; it felt like there were intruders in the backyard, and those intruders had five-inch-long serrated teeth.

The trauma that communities in the outer Cape felt after Arthur Medici’s death was very real. With it, however, came sometimes another feeling: that the risk Medici faced in the ocean that day shouldn’t have been allowed in the first place. Here, Cape Codders’ views were shaped by “shifting baselines,” or the tendency to assess our environment according to recent memory.

“The human lifespan shapes our baseline,” explained Catherine MacDonald, a researcher at the Field School Miami who studies sharks and shark-human conflict. “This is a wonderful success story from an ecological health perspective, but people feel like [the sharks] don’t belong there because they weren’t there when they were younger.” To those people, living with sharks can feel like they’re being asked to assume a new and unusual risk. “In fact,” said MacDonald, “we’re kind of having to consider the possibility of living in a world that’s not completely dominated by human choices and preferences.”

“We’re kind of having to consider the possibility of living in a world that’s not completely dominated by human choices and preferences.”

Perceived risk and those shifted baselines can produce some drastic ideas. Here on the Cape we’ve heard stirrings of interest in lethal methods of shark control, most famously from vocal Barnstable County Commissioner Ron Beatty, who called for a great white cull after Medici’s death. In the years since, he’s also advocated for culling seals, a concept some fishermen (echoing their 19th-century predecessors) also support to “protect” fish stocks. Indeed, every time this concept is raised, news reports find everyday Cape Codders—fishermen, surfers, snowbirds and year-rounders alike—who support it. But it’s difficult to establish how widely-held this sentiment really is.

Indeed, suggestions for Cape Cod’s shark “problem” have ranged widely, from creating barriers out of bubbles or kelp, to wearable electromagnetic devices for surfers and swimmers, to giving seals birth control. If there’s a trend in all of these solutions to the shark “problem,” it’s that they focus on actively shaping the natural world to fit human needs.

The world of social science offers a surprising alternative. Some research suggests that what humans need is not to re-tool the environment, but to become more intimately acquainted with it. In other words, humans don’t need fewer interactions with sharks, but instead more of them.

Like many of the shark scientists I’ve spoken to, Christopher Pepin-Neff describes his childhood self as “a shark kid,” from the pile of books he kept next to his bed to the shark cut-out he pasted on the wall.

What’s unusual is that Neff is not a biologist or an ecologist; he’s a social scientist. A senior lecturer at the University of Sydney, Pepin-Neff has spent the last decade looking into the laws, politics, and media that surround sharks and shark bites. He’s even received death threats, as his work often runs counter to beach protection measures that give locals a sense of security. But he was surprised when he started calling people after shark bites.

“Even in the face of the worst press sharks could get for 20 years, the public still doesn’t blame the shark,” Pepin-Neff found. “No one is telling this story, and yet the public still totally gets it.”

That revelation came from studies in Cape Town, South Africa, and in East and West Australia, where Pepin-Neff surveyed community members before and after a shark bite occurred nearby. In all three locations, there was no statistically significant change in people’s pride in having sharks in their environment, nor in their confidence in local efforts to protect swimmers. In both Australian towns, Pepin-Neff also tested if people were more afraid of sharks after attacks, and again found no significant difference.

Pepin-Neff can’t definitively say why the people he surveyed have such tolerant attitudes towards sharks, but another of his experiments may provide a clue. In surveys performed at the Sydney Aquarium, Pepin-Neff had visitors describe their feelings about sharks before and after walking through the aquarium’s shark tunnel, where they were surrounded by fins and teeth on all sides. One-third of them were primed to consider the sharks’ intentions: they were asked how good the sharks’ eyesight was, whether they thought the sharks could see them, and whether they thought that sharks in the wild tended to avoid humans. Another group received a science-focused message that focused on the statistics of shark bites. A control group received no message at all.

Remarkably, all of the people surveyed reported being less afraid of both sharks and shark bites upon leaving the shark tunnel than when entering—and those who had thought about the sharks’ intentions displayed greatest reduction in fear. It seemed that seeing sharks, and particularly gaining a better understanding of them, seemed to make people less afraid.

These findings also jibe with the experience of scientists and educators elsewhere. Take Cape Town, where in 2004—following a handful of shark bites in less than a year—an organization called Shark Spotters started placing lookouts on coastal mountains. They set off an alarm whenever a white shark is seen close to shore. According to Sarah Waries, the Shark Spotters founder, knowing that sharks are frequently close to shore, yet doing no harm, has changed the way the community responds.

Previously, any alarm would clear the beach for the rest of the day. “Now we set the siren off, they wade out of the water, and they get irritated and ask us, ‘How long is the shark going to be here?’” said Waries. “And then they go straight back in.”

“There is a mythical public attitude that people don’t like sharks, or that people take it out on the shark” when someone is bitten, said Pepin-Neff. This is the classic Jaws narrative: that marauding sharks must be hunted down to ensure community safety. In 2004, Pepin-Neff documented how this very narrative was used, following a series of bites, to support shark hunts in Western Australia despite public opposition.

This work has led Pepin-Neff to conclude that politicians and news reports are more to blame for this bloodthirsty narrative than the public, or the shark itself. “If you want to look for someone who is manipulating the public for their own political benefit to maintain power, when something terrible has happened, that’s politicians,” he said. Media, he added, exacerbates this by tending towards sensational language, such as saying a shark is “lurking” around a beach.

This disparity between public views and government actions results in a battle for our imaginations.

This cycle can spur governments to oversteer in their response, enacting policies with the greatest apparent effort in order to prevent political backlash. For example, after a series of shark bites in Western Australia, the government adopted a practice of killing any large shark over three meters in length caught on baited drum lines—hooks attached to a floating buoys that are fixed in place by an anchor—near beaches. The practice ended in 2014, though the government reserved the right to reinstate it.

In Queensland, Australia and KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa, lethal nets and drumlines have been standard practice for decades. Recent policy changes in both locations require that any animals found alive, sharks included, are supposed to be tagged and re-released. However, many animals die before this can happen. Between 2013 and 2017, an average of 83% of sharks and 55% of bycatch animals, like dolphins and turtles, died in KwaZulu-Natal’s nets and on its drumlines.

These lethal programs not only harm marine ecosystems. It’s also unclear if they make humans safer. The Queensland and KwaZulu-Natal governments both credit their programs with preventing fatal shark incidents. However, a 2019 review of Queensland’s program suggested that increased beach patrols and improved emergency responses played a much larger role. The West Australian drumline program targeted great whites, believed responsible for the prior attacks, but didn’t catch even one—and instead hooked many other species as bycatch. Elsewhere, a review of the shark culling program in Hawaii between 1959 and 1976 found that the culls didn’t change the rate of local shark attacks.

This disparity between public views and government actions results in a battle for our imaginations. The sources of information that we are supposed to trust appeal to emotion: they tell us that sharks are enemies to be repelled from the gates. Yet our own experiences appeal to logic: when we have time to interact with sharks, and with their environments, we understand their intentions are not those of targeted killers, but simply wild animals.

MacDonald, of the Field School, likened the effect to how routine interaction with cars teaches us not to fear driving despite the potentially grave risk it poses. “Most of us don’t have the kind of relationship with sharks, where we have many benign interactions with them,” she explained, before qualifying herself: many people do in fact have interactions with sharks, “but we hardly ever know about them.” In the wild, most sharks remain nearby but unseen, minding their own business.

All this suggests that, when it comes to coexisting with sharks, what Cape Cod may need is akin to exposure therapy. The bad news is that, like any form of therapy, changing the way you think takes time as well as effort. You have to ride the roller coaster repeatedly to learn it won’t hurt you. Yet it’s important that Cape Codders, and humans more generally, take this ride.

If our relationships with sharks are no longer dominated by fear, programs like culls should cease to be a reflexive response to potential conflict. People might also be more attentive to other actions and policies that affect sharks, such as fishing bycatch, climate change policy, and the creation—or dissolution—of marine protected areas. We might better see the ocean not as a resource for our utilization, but as it truly is: as the edge of an alien nation, where humans are never much more than visitors for whom evolution packed the wrong suitcase.

On a pearly gray morning in mid July 2020, I set off walking up the Cape Cod National Seashore in search of the animal I’d spent so much time talking and thinking about. I’d been told about a spot just up the beach from Head of the Meadow where seals like to congregate. I figured if there’s anywhere I might see a shark, it would be here.

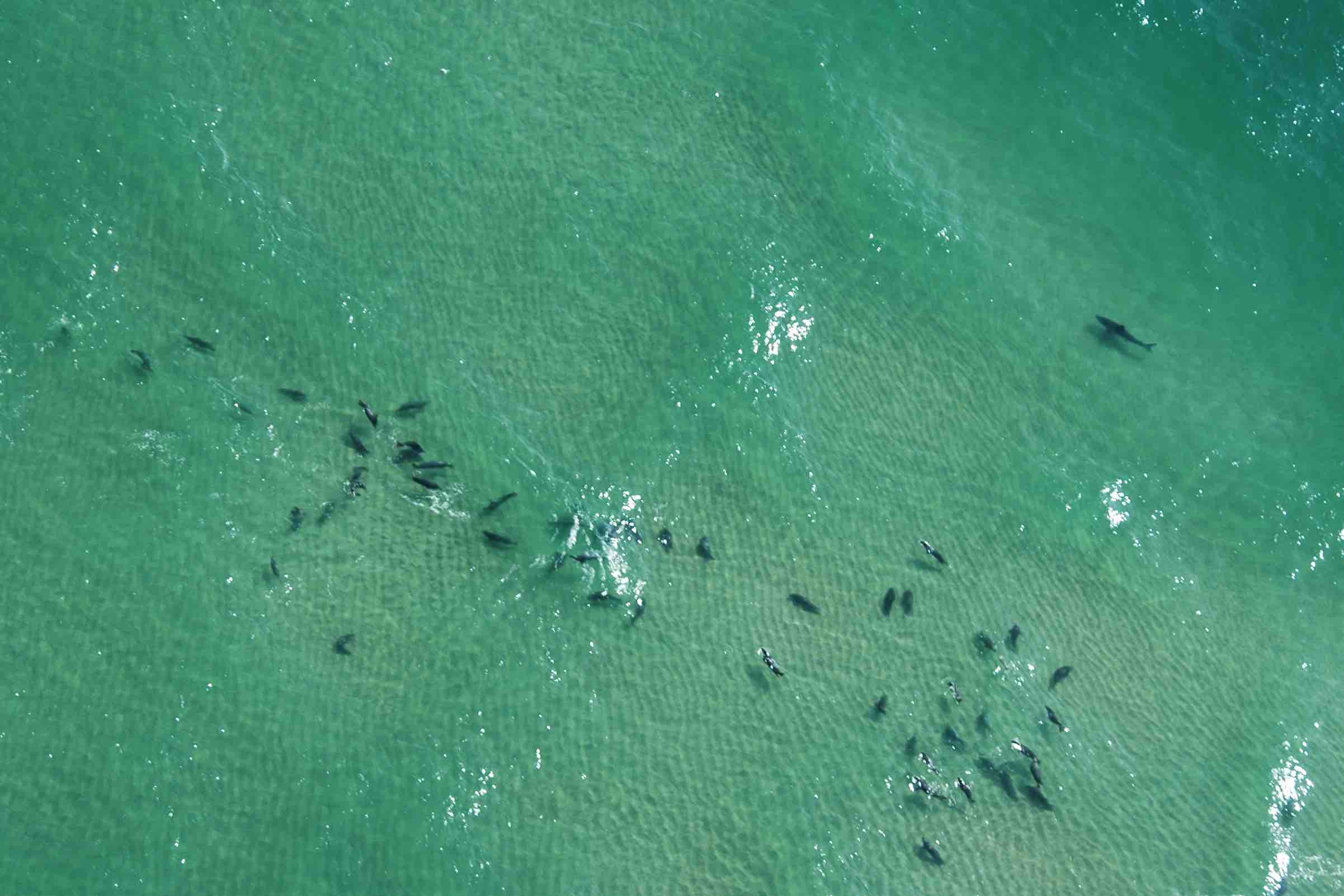

After about twenty minutes of walking, I found them: a congregation of nearly 100 gray seals, bobbing less than ten feet offshore. Their heads turned in sync. Enormous black eyes tracked me as I plopped down on shore.

Gray seals, it turns out, spend most of their days in supreme repose. They mostly loll in the surf, groaning in voices that can sound eerily human on the breeze. Occasionally, a few band together to corner schools of young striped bass against the shore. No sharks arrive, though that doesn’t stop my imagination from summoning them. Gray seals’ favorite way to relax appears to be bobbing, like buoys, heads just poking above the water, and in this pose their triangular noses look surprisingly similar to dorsal fins.

The sharks’ presence was very real out there—much realer than it was when I was writing about them from my house on the Buzzards Bay side of the Cape, which is warm and seal-free and rarely, if ever, sees a great white. I find my pulse is up, my senses sharpened. I’m keenly aware that over the last few weeks the Atlantic White Shark Conservancy has logged dozens of sightings on this coastline, including a few off this very beach. As time goes on, I’m increasingly unsure what I would do if a shark did arrive.

It brings to mind an apt comparison: a friend once said that the way we humans feel about sharks is not so different from how we feel about other large predators, like wolves and bears. We love the concept of them, cheering as they slice across our screens during Shark Week, or howl with unbridled freedom at the moon in movies, or splash playfully after salmon in glossy magazine photos. But when these predators stroll or swim into our own environs, our feelings about them get a little more complex.

“Sharks are definitely making it into the news, but people still have a lot of questions,” explained Marianne Long, education director at the Conservancy, a Cape-based white shark research and education nonprofit. The organization recently started a beach education program, dubbed Shark Smart, that places volunteers on local beaches to answer questions. Throughout the year the organization also runs talks and workshops that draw hundreds to learn about “Living With White Sharks,” as one recurring event is called. During the coronavirus pandemic, talks have gone online.

As they begin to grapple with sharks’ permanent new presence, many outer Cape towns are doubling down on education and outreach. Lifeguards are trained in shark behavior and how to advise beachgoers on shark-smart habits. Guards learn specific “stop the bleed” practices for bites, and the Conservancy teaches the same techniques to the public. On remote beaches, towns have started stocking kits with special bandages and tourniquets to address heavy bleeding. Some beaches are adding 911 call boxes and cell signal boosters, to compensate for the poor service in the area.

Meanwhile, the understanding that Pepin-Neff documented in Australia and South Africa is already beginning to shift on the Cape.

“We’ve morphed from a society believing the only good shark was a dead one to knowing that we need to protect these animals.”

“In general, I’ve seen a massive evolution in thinking when it comes to sharks,” said Greg Skomal, a senior fisheries biologist with the Massachusetts Division of Marine Fisheries and the de facto expert on great whites around the Cape. While his professional focus is on satellite-tagging great white sharks and trying to learn more about their lives, Skomal dedicates some of his remaining time to teaching lifeguards, officials, and the public alike, by holding workshops and public talks on coexistence.

“Over the course of my 35 years doing this, I think we’ve morphed from a society believing the only good shark was a dead one to knowing that we need to protect these animals, or at least manage them sustainably,” he said.

Many tourists at Head of the Meadow echoed this sentiment. Most told me that they wouldn’t risk swimming far from shore, but despite that fear, recognized that the ocean was a wild place.

“It’s their ocean, it’s where they live,” said Julia Jolliff, who was visiting from Ohio with her husband and three sons. “And I’m sure some people don’t like it, you know they can’t swim as much or surf or whatever. But I think figuring out how to live with them is totally important.”

Skomal noted that there will always be some people who resent sharks’ presence. For the surf shop or bed-and-breakfast who sees bookings drop off after a bite, he understands where they’re coming from. But Skomal, and many of the shark experts I spoke to, agreed that communities learning to live with sharks simply need time to let that exposure therapy take effect. That’s why it’s so important to have shark education programs in these communities, said Sarah Waries of Cape Town’s Shark Spotters, even if the risk of a shark bite remains relatively rare.

“Shark bites cause psychological trauma for the whole community, even for people who don’t use the beach regularly,” Waries said. She remembers, following a spate of bites in Cape Town in the early 2000s, when beachfront coffee shops were struggling to find customers, and lifesaving groups couldn’t get anyone to sign up for guard training. Even if the actual risk is low, community fear still needs to be managed.

I spent more than an hour watching the seals before admitting to myself that the odds are probably not in my favor. As the sun starts peeking through the clouds I gathered my sneakers and my sopping backpack, ambushed by the incoming tide. I headed back along the frozen wave of dunes.

Walking along the seashore, it’s still easy to imagine yourself back on Thoreau’s Cape Cod. Out here there’s nothing but the breath of the Atlantic, the call of gulls, and the endless shoreline; in my time with the seals, I see only two other people.

This timeless feeling is, after all, what draws many people out to this improbable spit of sand. If people have learned to love that, perhaps they can love the wild ocean that comes with it—sharks and all.

Lead image: A great white shark off Guadalupe Island, Mexico. Credit: Elias Levy