Every year, as shifting currents pull cold, nutrient-rich waters up from the Pacific Ocean depths, the western coast of South America floods with fish. Billions of anchovies follow the currents in flickering silver masses, and in turn are followed by fleets of fishing vessels.

Conservation scientists follow this catch, too, trying to prevent overharvesting that will cause populations to plummet and jeopardize the many other creatures—larger fish, sea lions, dolphins and sharks, and seabirds—who also depend on the anchovies. This year, these monitors have some unusual assistants: As seabirds flock to the feast, they’ll be carrying GPS-equipped cameras to monitor the ships below.

“They are an independent, non-biased way to record fishing activities,” says Carlos Zavalaga, a seabird ecologist at Peru’s Scientific University of the South, who leads a project that uses kitted-out Peruvian boobies to monitor the country’s anchovy fisheries. “They just go and feed.”

Those birds provided an unwitting view into illegal, unregulated, and unreported fishing

Scientists started sticking gauges and radio trackers on large-bodied animals back in the 1940s, but the advent of GPS, satellite transmission, and miniaturized electronics opened the field up to track smaller, lighter, and farther-traveling animals. Seabirds are stars of this research, and it has yielded extraordinary insight into the lives of creatures capable of drinking seawater, going weeks without food, and of flying halfway around the globe without ever touching land.

It was Henri Weimerskirch, a seabird researcher at the French National Centre for Scientific Research, who first thought to employ them as spies. While tracking how young albatrosses spend their first few months at sea, he realized that he could sometimes see the birds following and hunting around fishing vessels. Sometimes the boats were fishing in areas they were not supposed to be—or were not supposed to be fishing at all.

Those birds provided an unwitting view into illegal, unregulated, and unreported (IUU) fishing, which poses a threat to the sustainability of the ocean’s already-stressed fisheries. One estimate suggests that these catches annually amount to as much as 26 million tons of fish, or nearly one-third the total of all legal fisheries.1 Another puts the price tag of IUU fishing at $26 to $50 billion lost from the legitimate fishing industry.2 And neither of these numbers captures the additional scale of bycatch: fish, marine mammals, and seabirds caught accidentally and, often, killed in these fisheries.

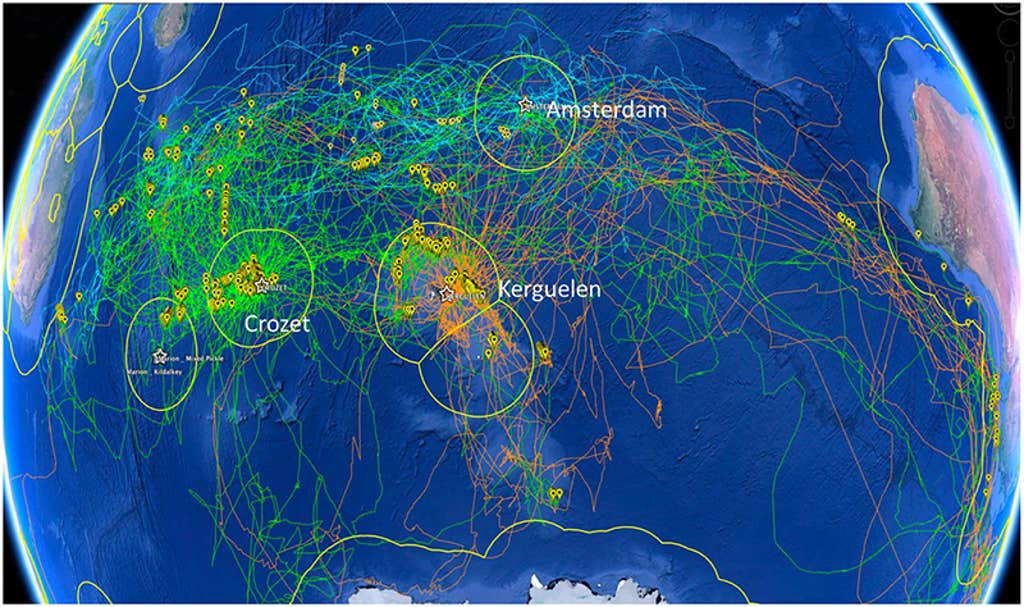

Weimerskirch wondered whether seabirds might be used to track those vessels. To investigate the possibility, he fitted 169 albatrosses living on islands in the southern Indian Ocean with GPS trackers and devices that detected the radar signals boats use to navigate.

The birds ranged across more than 29 million square miles of ocean, including forays into the icy, storm-tossed Southern Ocean around Antarctica.3 They encountered 353 different boats, of which 28 percent were fishing without an Automatic Identification System (AIS). This radio-operated system automatically identifies a vessel and its position, speed, and direction; turning it off, or operating without one, is not only illegal within roughly 200 miles of land but is usually a sign that a boat is trying to hide something.

Weimerskirch was particularly encouraged by the possibility that these birds could, potentially, help tackle the thorny challenge of monitoring IUU fishing in the Southern Ocean, one of the most remote places on Earth. “In most places, you can use other ways to monitor illegal fishing—planes or drones or at-sea spotters,” he says. “But in the Southern Ocean, there is nothing.”

The possibilities don’t end there. “The risks of IUU fishing are in every ocean and across many different fleets,” says Elizabeth Selig, the deputy director of Stanford’s Center for Ocean Solutions. And even when planes or drones or spotters are available, the vast scale of their task is daunting. Seabirds may still have a role to play.

Luckily seabirds, like illegal fisheries, are found globally. While some species are better-suited than others to being fitted with trackers—albatrosses, for example, are known for being remarkably easy to work with—technological advances mean these devices are becoming even smaller and lighter, making it possible to tag seabirds as small as one-pound Atlantic puffins, lighter than a loaf of bread.

Since his initial study, Weimerskirch has connected with researchers in New Zealand, the United Kingdom, and the United States who have also adopted his technique. Researchers from BirdLife international, a global conservation group, are using it to figure out which legal fleets to target for bycatch mitigation measures.

If illegal fishing is not curbed then seabirds will face a grim future.

Selig notes that seabirds will never fully replace other monitoring systems. Their movements are not entirely predictable, so one can’t plan for them to visit a specific area at a specific time; and even if a boat looks suspicious, it’s not always possible to know whether they’re actively engaged in fishing. Nonetheless, she sees seabird monitors as “another piece of the enormous puzzle,” providing data that can be used to flag areas for further scrutiny.

More fine-grained information might yet be possible, though. The cameras that Zavalaga is fitting onto anchovy-eating Peruvian boobies are able to capture, so long as photographic conditions allow, the names and license numbers of boats.

Of 31 boats that Zavalaga’s tagged boobies spotted during the first phase of his research, five were unregistered. Two were fishing in marine protected areas where fishing is illegal. His latest project, monitoring both artisanal and commercial fisheries, will collect and transmit daily reports to fishing regulatory agencies, with the aim of providing more actionable day-to-day information. “What we want is not to replace the surveillance system, but to complement it,” Zavalaga says.

And what of the birds themselves?

Researchers have labored to make the technology as small as possible to avoid disrupting the lives of their sentinels. But this is still extra weight, carried sometimes for tens of thousands of miles. A 2019 review of tracking devices on birds found that the effects can vary widely, from increased preening at the low end to early mortality at the most extreme.4

Impacts were less severe when sensors were smaller relative to a bird’s weight. As a result, large-bodied seabirds—like Weimerskirch’s albatrosses and Zavalaga’s boobies, whose equipment amounts, respectively, to less than 1 and 2 percent of their weight—were least likely to have problems.

That did not mean there were none, though. Sensors had a tendency to decrease breeding success, and this had no relationship with body size. Managing these effects is a challenge—but if illegal fishing is not curbed then seabirds, already threatened by climate change, bycatch, and invasive species, will face a grim future. Using seabirds as monitors should ultimately help the birds, too. ![]()

Lead image: A wandering albatross fitted with a GPS tracker and sensors that detect the radar used by boats to navigate. Credit: A. Corbeau

References

1. Song, A.M., et al. Collateral damage? Small-scale fisheries in the global fight against IUU fishing. Fish and Fisheries 21, 831-843 (2020).

2. Sumaila, U.R., et al. Illicit trade in marine fish catch and its effects on ecosystems and people worldwide. Science Advances 6 (2020).

3. Weimerskirch, H., Collet, J., Corbeau, A., & Patrick, S.C. Ocean sentinel albatrosses locate illegal vessels and provide the first estimate of the extent of nondeclared fishing. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 117, 3006-3014 (2020).

4. Geen, G.R., Robinson, R.A., & Baillie, S.R. Effects of tracking devices on individual birds—a review of the evidence. Journal of Avian Biology 50 (2019).