In a beaux-arts building in central Philadelphia lurks a vast and unusual collection: It includes a tumor extracted from President Grover Cleveland, slices of Albert Einstein’s brain, and a large assemblage of skulls, swallowed foreign objects, forceps, and other medical miscellany.

Dating to 1858, the collection was started with the goal of improving training for physicians by providing them with models and tools from which to learn. In the intervening 165 years, it has grown to more than 30,000 items, a trove of teaching objects that helps to illuminate the often murky history of medicine.

The public is welcome to walk the halls and exhibitions of the Mütter Museum, a division of the College of Physicians of Philadelphia. But the vast majority of these objects de medicine have been stored away, out of view. That is, until recently, when the College launched an ambitious project to photograph and display the bulk of their collection online.

Lisa Geiger, a former urban archeologist, leads the project as the College’s digital-collection specialist. We asked her to share five objects she finds most fascinating.

1. MEDICINE KIT

This medicine kit holds what are likely late 19th-century pharmaceutical preparations. Among the preparations are “spirit of nitrate,” says Geiger, adding that, “I love the one that’s just a brown mixture for ‘coughs, colds, and hoarseness.’” The tonics were prepared by two Philadelphia pharmacies that were both in operation from 1860 to 1890. The language on bottles “speaks to the relationship that a doctor would have to the pharmacist, who might individually tweak the recipe in the way the doctor would want,” she says.

2. INFANT ARM MODEL

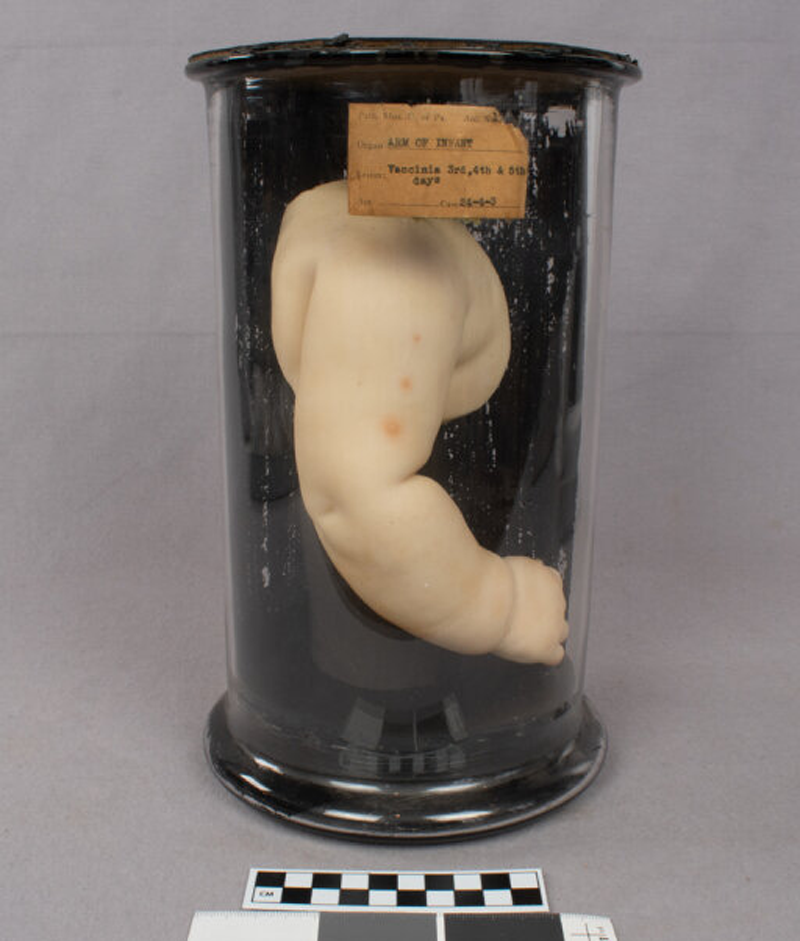

In the mid-19th century, vaccines for the deadly scourge of smallpox began to spread. This wax model of an infant’s arm, created by British sculptor Joseph Towne, shows the progression of a normal reaction to the inoculation, so that physicians could learn what to expect—and what might be considered worrisome. Artifacts like this can bring to life past shortcomings of the medical profession. As Geiger notes, “almost all of Towne’s work that I’ve seen depicts pale skin. And it really ignores a range of how doctors were to recognize and diagnose dermatological conditions on people who have darker skin.”

3. STAGHORN CALCULUS

This teaching tool is an organic one—formed inside of a patient’s kidney. A staghorn calculus (a form of kidney stone), fills in nearly all of the internal spaces of the organ, revealing its shape in painful detail (after being surgically removed). In addition to a medical specimen, it captures a moment in time when growths like these could suddenly be detected, for example, with X-ray, which became more commonly available in the early 20th century.

4. HORSE LEG

This 19th-century replica of a horse leg, showing a common degenerative joint condition, was created by a French anatomist, Louis Auzoux, who invented his own form of paper mâché for his models. They could be precisely assembled and disassembled to reveal different parts of the anatomy—and how they fit together. Through Auzoux’s models, doctors could learn—hands on—about the progression and treatments of diseases. “This one has so many little pieces, and they’re just beautifully constructed,” Geiger says. “They’re like works of art.”

5. DIATHERMY MACHINE

This 1955 machine used electricity to generate heat alleged to have therapeutic value. “Diathermy grew into a medical idea after people, including Nikola Tesla, proposed using electricity as a type of medicinal therapy,” she says. A limb might be strapped into the clamp, and then a disc placed against the patient’s body would run an electric current through it, creating heat. The data on their efficacy is scant, but, she says, as a piece of medical history, objects like this are important to retain. “Their imposing nature made them look like they were therapeutic.”

What about Einstein’s brain? It was a no-brainer first search in the catalog, but the results turn up: “image not available.”

The museum, like so many others around the globe, is in a period of reckoning about how to handle and display human remains—many of which were collected without consent or even clear provenance.

As they muddle through questions about those trickier assets, Geiger and her colleagues will continue rooting through the collection, opening century-old doctors’ bags to see what they hold—and documenting them for posterity. ![]()

All images courtesy of the College of Physicians of Philadelphia.