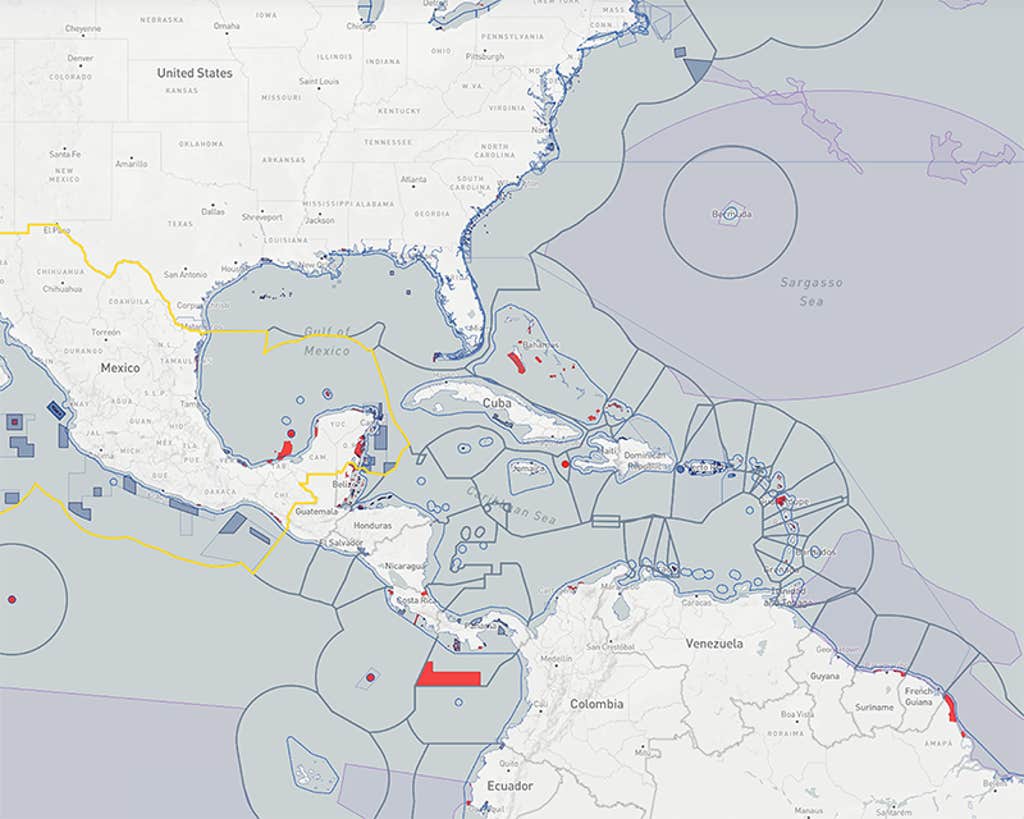

Setting aside 30 percent of Earth’s lands and waters by the year 2030: This goal dominates much of the current conversation about global biodiversity conversation. It’s an inspiring idea, something tangible to reach for. Yet even as countries claim that more than 8 percent of the ocean is currently protected, a comprehensive new mapping and database tool shows that protections are robust in just 3.4 percent of the ocean.

Those discrepancies illustrate the challenge posed by the 30×30 initiative, agreed to by nearly 200 nations in December 2022 as part of the United Nations Biodiversity Conference in Montreal, Canada. They also illustrate the gulf that may exist between sweeping claims about safeguarding vast swaths of the ocean and nitty-gritty, in-the-water realities.

Making these analyses possible is the ProtectedSeas Navigator, which was launched in June and is free to use. Navigator emerged from a recognition that a necessary step in improving ocean protections is knowing what’s already in place—but that information is often difficult and time-consuming to assemble. “People hear ‘regulations’ and ‘legal’ and think: ‘Oh, snore,’ right?” says Jennifer Sletten, an attorney at ProtectedSeas, a program of the conservation nonprofit Anthropocene Institute. “It’s really a cornerstone of protection.”

“To a biologist like me who does not want to dive into legal texts, it’s a gift.”

Other databases of marine protection lack Navigator’s global scope—it includes information about more than 21,000 locales, from coastal waters to the high seas—or only delineate the boundaries of protected areas without providing details about how they are regulated and managed. For someone trying to figure out if a vessel is fishing illegally or if a whale population’s entire range is stringently protected, existing resources are not always helpful.

To help whale advocates, fishing monitors, and other people who need to know about a particular marine locale, the Navigator’s database includes formal Marine Protected Areas (MPAs) as well as places with intermediate levels of protection, such as fisheries management areas where some human use is allowed but with restrictions aimed at preventing overfishing. That’s useful for Kristina Boerder, a marine biologist at Dalhousie University who studies how MPAs affect fisheries and vice versa.

The boundary of an MPA “is a very literally fluid boundary. And the fish don’t know where it is,” says Boerder, who consulted with ProtectedSeas on the Navigator’s development and now uses it in her own research. “We need to consider all the policies because the ocean is a very complex and dynamic space, and to be able to manage it properly one needs to have the overview.”

That overview took eight years and a total of 42 person-years worth of labor to produce. To characterize those more than 21,000 protected and managed areas, the ProtectedSeas team drew on reference material ranging from online information made available by countries, including Australia, New Zealand, Palau, and the Maldives to a photo of a sign at the Batalang Bato Marine Sanctuary in the Philippines. They even referenced “scans of typewritten documents with handwritten margin notes in Swedish,” recalls ProtectedSeas director Virgil Zetterlind. More than 2,400 of the areas had not been digitally mapped; the team painstakingly digitized their boundaries from legal descriptions.

“We’re hoping we save a lot of other organizations the work of doing this research,” Zetterlind says, ultimately speeding up efforts to assess existing marine protection measures and strengthening proposals for new ones. Earlier this year, the team analyzed sea turtle protections in the Caribbean using the Navigator’s data—a task they completed within weeks that would previously have taken months of slogging through legal texts.

“People hear ‘regulations’ and ‘legal’ and think: ‘Oh, snore.’”

Although the Anthropocene Institute does not advocate for specific protection measures, styling itself as “a neutral purveyor of information,” the new tool could be used to identify gaps in ocean protection, flag areas where regulations might be over-complicated, and prioritize where small changes could have the biggest impact. It might point to where existing protections are not having the desired effect because of poor design, poaching, or unrelated biological factors. And it could help advocates identify so-called “paper parks” where protections exist in name only.

The team also developed a five-level rubric to assign a “Level of Fishing Protection” to each area included in the database, representing the first time a unified such analysis has been applied at a global scale. “To a biologist like me who does not want to dive into legal texts, it’s a gift,” says Boerder, who has used the resource in a preliminary analysis of protections for highly migratory species such as sharks and tuna.

Navigator’s maps are already integrated with Global Fishing Watch, an organization that tracks the location of fishing vessels, which could enable real-time detection of illegal fishing activity. ProtectedSeas is also working with the International Hydrographic Organization, which sets global standards for electronic navigational charts, to develop a Marine Protected Area data format for use in future charting.

The next steps, according to Zetterlind, are to develop procedures to keep the database up-to-date and track the evolution of ocean protections over time. ProtectedSeas wants to add information about locally and Indigenous-managed areas, and assess whether regulations are being followed and enforced. That latter goal will require extensive collaboration with local organizations, but “it is sort of the natural next question,” he says.

Navigator could also be used to track progress toward the 30×30 goal. But others could track progress differently, cautions Angelo Villagomez, a marine conservation specialist with the Center for American Progress. Historically, environmental groups have taken a stricter view of what counts as “protected,” while industry groups tend to favor a more expansive definition. Although Villagomez calls Navigator “a really great resource,” its numbers could be crunched in various ways.

“How much of the ocean is protected? It really depends on who you’re asking,” Villagomez says. “And so the benefit of the Navigator and the data that they’ve collected is really going to depend on how it ends up being used.” ![]()

Lead image: Misbachul Munir / Shutterstock