Ash Jogalekar, a chemist and science writer, recently posted a list of “academic papers” that “stand as timeless testaments to both great thinking and great writing.” Ash’s list got me thinking about papers I admire. I’ve given this topic a lot of thought, because I’m always on the lookout for readings to assign in my humanities and science-writing classes. Ideally, these readings should be short and punchy, conveying big ideas in small packages. They can be challenging but not opaque. If I happen to know the author, that’s a plus, because I can provide a little background. Collectively, the readings should cover a lot of intellectual territory. Here is my list of 10 papers, in chronological order. Not to brag, but I have met and can gossip about the final six authors.

“The Communist Manifesto”

Karl Marx and Frederick Engels. 1848.

Yeah, communism has been a failed experiment; even China’s economic upsurge stems from controlled capitalism. I nonetheless make my students read the first section of this infamous polemic because it does a great job detailing the upside as well as downside of capitalism. Capitalism, Marx and Engels acknowledge, has undermined repressive institutions such as religions and monarchies while promoting literacy and female equality; the problem is that it inevitably leads to devaluation of workers. This 19th-century analysis of capitalism remains all-too-relevant. Aren’t the billionaire tech bros producing their own “gravediggers”?

“War Is Only an Invention—Not a Biological Necessity”

Margaret Mead. Asia, 1940.

Social-injustice warriors love bashing Mead. The hell with them, she was a great scientist. In this paper, Mead refutes the insidious idea that war is the inevitable consequence of evolutionary impulses. Subsequent research has corroborated her claim that war is an “invention,” like marriage and trial by jury. Writing at the dawn of World War II, Mead acknowledges that eradicating war will be hard, because it is so deeply rooted in our culture. Mead nonetheless gives me hope that we can end war if we have the will to do so.

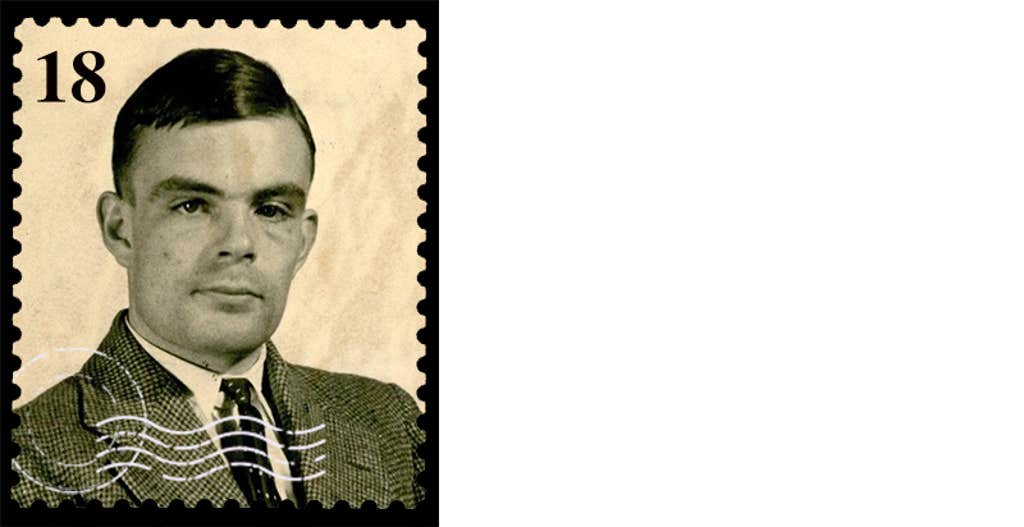

“Computing Machinery and Intelligence”

Alan Turing. Mind, 1950.

This paper doesn’t just introduce what we now call the Turing test, a method for determining whether a machine can think; it’s also loaded with profound, witty arguments about the nature of intelligence and mind, arguments even more relevant in the era of ChatGPT. Make sure you note Turing’s riff on extrasensory perception.

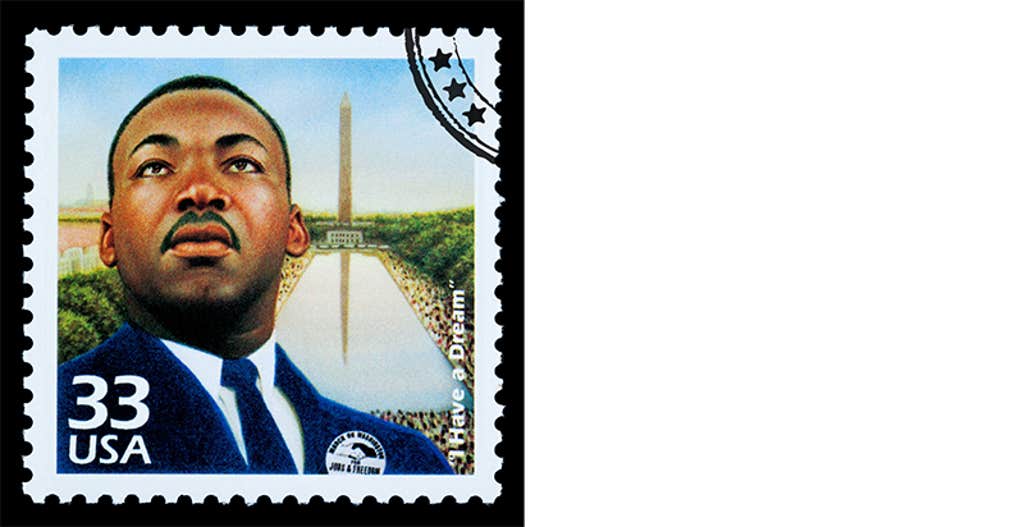

“The quest for peace and justice”

Martin Luther King. Nobel Peace Prize Lecture, 1964.

King’s moral clarity has become even more impressive over time. “There is a sort of poverty of the spirit,” he warns, “which stands in glaring contrast to our scientific and technological abundance.” Yup, still true. King urges us to work against racism, poverty, and war while remaining nonviolent. Nonviolence is a hard sell in our cruel era, but we must embrace it to create a just, free, peaceful world. Good thing we have those altruism genes (see next entry)!

“The Evolution of Reciprocal Altruism”

Robert Trivers. The Quarterly Review of Biology, 1971.

Why, if we’re bundles of mean, selfish genes, are we ever kind to each other? And not only to kin who share our genes but to strangers? Drawing upon evolutionary and game theory and animal ethology, Trivers proposes an elegant, persuasive answer. Trivers’ insights into our twisted psyches, which make more sense than Freud’s, helped spawn sociobiology and evolutionary psychology. If you wonder why Trivers isn’t better known, check out my profile of him.

“What Is It Like To Be A Bat?”

Thomas Nagel. The Philosophical Review, 1974.

Best title ever for a philosophical paper! The text is terrific, too. Nagel is one of those rare philosophers who writes well and avoids getting bogged down in definitional nitpicking. Here, confronting what David Chalmers—two decades later!—dubbed “the hard problem,” Nagel explains why consciousness is a uniquely intractable puzzle that might forever elude scientific solution. Integrated information theory? Give me a break.

“Is the End in Sight for Theoretical Physics?”

Stephen Hawking, Physics Bulletin, 1981.

Published seven years before A Brief History of Time made him a celebrity, this paper presents, in three brisk pages, Hawking’s audacious vision of a unified theory, or “theory of everything,” that solves the riddle of our cosmic existence. Based on the twist at the end, you have to wonder: Was Hawking kidding all along? My students find this paper tough, but it gives me an excuse to brag about the time I carried Hawking in my arms.

“The Man Who Mistook His Wife for a Hat”

Oliver Sacks. The Man Who Mistook His Wife for a Hat and Other Clinical Tales, 1985.

This case study, after which Sacks’ bestselling 1985 collection is named, showcases his remarkable combination of literary and scientific talent. Sacks’ contemplation of a patient’s broken brain leads to deep reflections on how healthy brains make sense of the world. And yet Sacks is an ardent anti-reductionist, who implies that no theory can encompass us all, because each of us, even the most damaged, is unique. Sacks renders what could be a sappy truism into a rich, humane vision of humanity.

“Information, Physics, Quantum: The Search for Links”

John Wheeler. Proceedings of 3rd International Symposium on Foundations of Quantum Mechanics, 1989.

Wheeler, a hard-nosed physicist with mystical yearnings, proposes fusing quantum theory with information theory, a notion he condenses into the phrase “it from bit.” He elaborates that “every it—every particle, every field of force, even the spacetime continuum itself—derives its function, its meaning, its very existence entirely—even if in some contexts indirectly—from the apparatus-elicited answers to yes-or-no questions, binary choices, bits.” Wheeler’s “it from bit” helped inspire the thriving field of quantum information science; it also gives succor to those who suspect mind matters at least as much as matter. For more background, see my profile of Wheeler. This is the only paper on this list I haven’t assigned to students—yet.

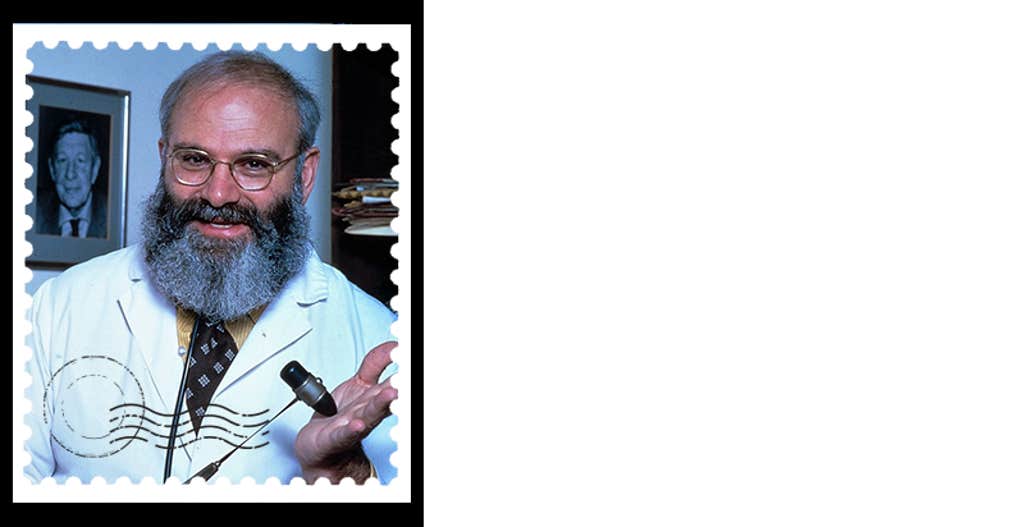

“Why Most Published Research Findings Are False”

John Ioannidis. PLOS Medicine, 2005.

This paper by Ioannidis, an epidemiologist, triggered what came to be known as the replication crisis. Ioannidis calmly, methodically, scientifically deals a devastating blow to science, from which it has not recovered. Ioannidis not only quantifies the unreliability of the scientific literature; he also traces it to scientists’ competition for fame and financial rewards; “hotter” scientific fields are more likely to produce bogus findings. I inform all my students about Ioannidis’ findings, which can help explain why, for example, cancer care is such a mess and science in general is stalling. ![]()

Lead image by Tasnuva Elahi; with images by nik93737, Stamptastic, spatuletail / Shutterstock