Combat in nature is often a matter of tooth and claw, fang and talon. But some creatures have devised devious and dramatic ways to weaponize their bodily fluids, expelling them in powerful streams for the purposes of attack or self-defense.

Researcher Elio Challita became fascinated by fluid ejections in nature when he began studying an insect called the sharpshooter, which pees one droplet at a time using a method called superpropulsion. These insects consume 300 times their own body weight per day in xylem sap, a watery solution of minerals and other nutrients found in the roots, stems, and leaves of plants. To efficiently expel the resulting waste, they use a kind of internal catapult that helps overcome the surface tension in the droplets.

Challita and a team of researchers from the Bhamla Lab at Georgia Tech decided to survey the biomechanics and fluid dynamics that govern fluid ejections across the animal kingdom to see what commonalities they could find. Among others, they identified a number of creatures that use bodily fluids as powerful weapons in the fight for survival. These fluid ejections defy gravity and rebel against traditional notions of predator-prey tactics.

The team’s review, “Fluid Ejections in Nature,” is forthcoming in the Annual Review of Chemical and Biological Engineering.

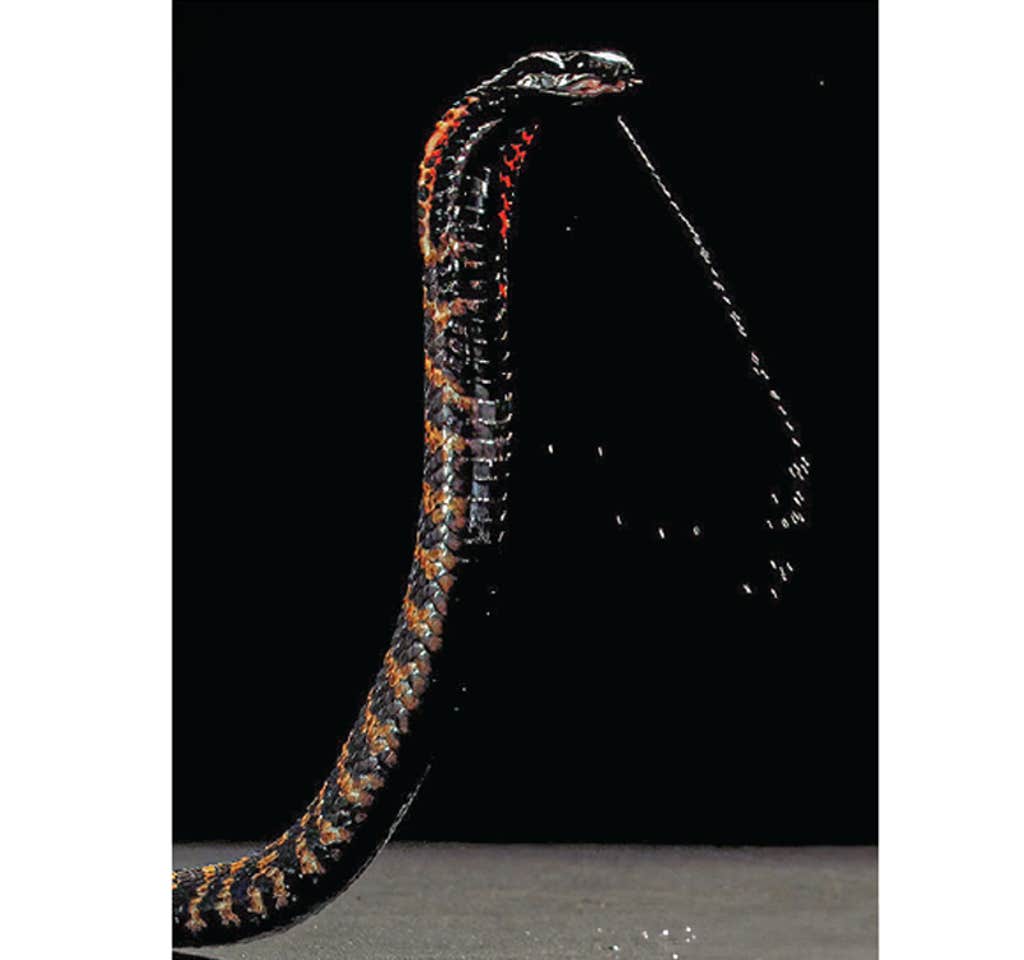

1. Ringnecked Spitting Cobra

Cobras of the Naja genus defend against threats by spitting venom with extreme precision toward the eyes of an enemy, up to 6.5 feet away. These snakes release the venom through hollow microscopic fangs and can adjust the distribution of their spit with rapid movements. Spitting cobras have a venom discharge orifice that is more circular in shape than non-spitting species, which gives the venom more forward force. Contraction in the venom gland also helps. A 90-degree bend near the lip of the orifice gives the snake more precise control over venom flow. Naja pallida cobras can spit venom at average speeds of 1.27 milliliters per second.

2. Archerfish

Dwelling in mangrove-filled estuaries and freshwater streams, archerfish actively hunt down land-based insects such as flies and spiders, as well as small lizards, by shooting water jets out of their specialized mouths. The fish create these jets by raising a bony tongue to the roof of the mouth, which forms a tube from which they can expel the liquid jet. The fish can spit these jets of water at speeds of 6 feet per second and accelerations of up to 400 meters per second squared—by comparison, a cheetah can accelerate at a rate of 10 meters per second squared. The jets have an impact force that is far more powerful than the anchoring force of small insects and bugs. The archerfish hone their jet-shooting skills for hunting as they grow and mature, improving both speed and precision. They can also estimate the trajectory of prey who have been struck by a jet and capture it before other predators get there first.

3. Bloody-Eyed Lizard

Horned lizards can shoot jets of blood from their eye sockets in self-defense against predators. The lizards contract the muscles lining the veins around the eyes abruptly, resulting in increased pressure that helps in the formation of jets. These blood jets or squirts can travel up to a distance of around 3 feet, and contain chemicals that are toxic to dogs, wolves, and coyotes.

4. Bombardier Beetle

Bombardier beetles store a solution of hydrogen peroxide, hydroquinones, and alkanes in one chamber in the back of their abdomens, and another solution of peroxidase and catalase enzymes in a second chamber. The moment they fear attack from a predator such as a toad, they mix the contents of the two chambers, which creates an exothermic reaction, bringing the temperature of the chemicals to a scalding 212 degrees Fahrenheit. The beetles discharge these boiling anal chemicals in pulsed jets at an average speed of around 33 feet per second for approximately 11 milliseconds. The bombardier beetle can control the direction of the spray using something known as the “Coanda effect,” a phenomenon by which the fluid flows along the curvature of a surface.

Lead photo:USFWS Mountain-Prairie / Flikr