They say, never meet your heroes. Daniel Dennett, who was exceptional in so many ways, and who died last month, was for me an exception to this rule, too.

Like so many, I was first inspired by Dennett on reading one of his many bestsellers: Consciousness Explained. It was 1991 and I was a fresh undergraduate with a powerful but undirected interest in consciousness. I had no idea how to go about studying it, or how to think about it. I was studying physics at Cambridge and had just plowed my way through Roger Penrose’s The Emperor’s New Mind, which had left me confused and despondent. Dennett’s book, with its presumptuous but oh-so-appealing title, was both a tease and a salve. I devoured it.

I didn’t agree with, or follow, everything. But I learned so much from his clear, witty writing, and from his famous “intuition pump” thought experiments. I was left with the strong impression that consciousness, if not explained, was explainable, and I now had a north star to steer by.

Learning from him could sometimes feel like looking straight at the sun.

Years passed. I thought I might meet him when he examined the doctoral thesis of a friend of mine who was studying with me at the University of Sussex, but it turned out they met over Skype. I would hear stories about him from one of my mentors at the University of Sussex and one of Dennett’s great friends, the philosopher Maggie Boden. These were tales of philosophical bust-ups, of sailing adventures, and of a voracious and seemingly unbounded intellectual appetite. The impression was of someone larger-than-life, who delighted in engaging with the world rather than preaching from an ivory tower. I read every book he wrote, and many of his papers. But the man himself remained remote.

I finally met Dennett in 2016. I’d recently joined a group of researchers at the Brain, Mind, and Consciousness Program of the Canadian Institute for Advanced Research, where Dennett had served as a long-time advisor. I remember feeling nervous when approaching him in the hotel bar before one of our meetings to say hello for the first time, but I needn’t have worried. Dennett was as approachable and avuncular in person as he was esteemed and revered in academia. Which is very. I don’t remember what we talked about then, but in the conversations and email exchanges that followed over the years he unfailingly exuded kindness, intellectual generosity, and perspicuity. He would tell you exactly what he thought, and he had the ability to do so in a way that made you feel improved, rather than dumb for making some stupid mistake.

Two examples stand out. The first is from seven years ago. I was in Vancouver, about to give a TED talk, and I was terrified. There were hundreds of influential people watching in person, and thousands more online. The next 16 minutes could be transformational or a total flop. But of all the people there whose opinions might matter, the one person I really didn’t want to disappoint was Dan Dennett.

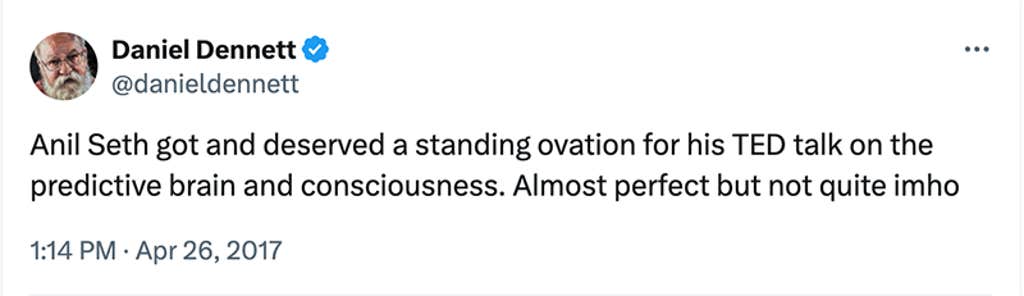

Afterward, amid the high-fiving and catharsis, I noticed a short tweet from Dennett.

“Almost perfect but not quite.” This combination of generosity and gentle criticism was typical. And he was right. In my talk I’d made the mistake of using the phrase “inner movie” to describe the multisensory immersive nature of conscious experience. But an inner movie implies an inner movie-watcher, a Cartesian homunculus of exactly the sort that Dennett—and I—wanted to expunge. This wasn’t a technicality. It was a give-away that I hadn’t really internalized the insight.

The second example was from a pandemic year. I was finalizing the first draft of my book Being You and, with some hesitation, I’d asked Dan if he’d be willing to consider writing a blurb for the cover. He declined, disarmingly—explaining that he’d decided some time back not to do any more blurbs, and if he changed his mind for me he’d risk upsetting many of his colleagues and friends he’d already said no to. But to my amazement he offered something much more valuable. He said he would set the draft as the reading for his next course at Tufts University, and then we could have two or three long Zoom sessions going through each chapter in detail with him and his class of talented students. It still astounds me that he took the time to do this, but he did, and the discussions we had in these sessions improved the book no end.

I never stopped learning from Dennett. I found myself coming round to his way of thinking on many things: the centrality of evolution for understanding the mind, how to think about free will (though in 2021 we found ourselves on opposite sides of a debate on the topic), and of course the absence of—or any need for—an inner observer, homunculus, or theater in the brain where everything “comes together.” But learning from him could sometimes feel like looking straight at the sun. I had to look away, to approach things sidelong, sparking the worry that I’d never fully grasp the weight of his arguments.

Dennett was often described as a philosophical “illusionist,” a position sometimes caricatured as saying that consciousness doesn’t exist. (A criticism of his 1991 book was that it should’ve been called Consciousness Explained Away.) But illusionism doesn’t, in fact, say this. On one reading, it says we are mistaken to think that the relationship between consciousness and physical, biological processes in the brain is a big mystery—the mystery that fellow philosopher David Chalmers calls the “hard problem” of consciousness. On another reading, which I’m more sympathetic to, it says that consciousness exists, but it might not be what we think it is—in the same way that the color red exists, but is not what we might think it is—there is no redness out there in the world nor is there a red “figment” in the mind, to borrow another of Dennett’s delightful terms.

I always looked forward to discussing these ideas with Dennett, and to chatting about them with my colleagues and friends, all of us trying to figure out what Dennett might really be thinking. One dimension of the sense of loss I now feel is that these discussions will become historical, a matter of interpretation and exegesis, rather than the living, vital process they so recently were.

In his later years, Dennett was fond of riffing on Chalmers’ hard problem with what he called the “hard question”: Once some (mental) content reaches consciousness, “then what happens?” This was his way of sending up the many theories that propose that conscious experience might somehow arise out of, or emerge from, this-or-that aspect of brain activity. Neurons fire in synchrony? Or with a certain form of complexity? And then what happens? In his diagnosis, the struggles of consciousness science lay in the systematic failure to properly ask, and answer, this question.

Daniel Clement Dennett was a gentle giant of the intellectual world. I, along with many others, will miss him deeply. He leaves an unmatched legacy in his books and papers, in how he brought philosophy and science together, and in the legions of students and researchers he taught and inspired. He was, I will assume, a materialist to the end. And in dying, perhaps Dan put his materialist beliefs to the ultimate test. And then what happens? ![]()

Lead image: Master1305 / Shutterstock