As the first blue hues crept into the otherwise lightless black sky, I carefully continued down the slippery ladder. Donning full scuba gear and tank—with a clipboard, fins, and underwater camera somehow all wedged, clipped, or balanced around my body—I sank into the inky, inscrutable water. Earthly burden lifted, I joined the weightless and serene world of the coral reef at dawn.

Crossing the Indonesian reef crest, with the sun rising behind me, I dropped down the coral wall, still in blackness save for a school of bioluminescent flashlight fish, whose symbiotic bacteria emitted an incongruous glow from specialized sacs beneath their eyes. My presence scared off these skittish biological lanterns, leaving the reef uncharacteristically quiet as I descended into the dark.

My goal at this unsociable hour was to become one of the privileged few humans to ever witness the birth of a pygmy seahorse. Enigmatic, charismatic, and poorly known, these miniature fish had been reluctant to give up their secrets, until now.

The true romantics of the ocean, some seahorses never re-mate, even after their partner dies.

Embarking on the doctoral research that culminated in my thesis, “The Biology and Conservation of Gorgonian-Associated Pygmy Seahorses,” I could never have foreseen what fascinating subjects they would make. In this first research into the biology of pygmy seahorses, I set out to explore their private lives.

Male pregnancy had already been confirmed for pygmies from museum specimens, but their natural behaviors on the coral reefs of Southeast Asia had remained a mystery since their rather accidental discovery in 1970. I couldn’t have predicted, therefore, that my notes on the species would read more like a novel of the Fifty Shades series than a scientific record, revealing many of these mysterious animals’ darkest secrets.

The most well-known and fascinating aspect of seahorse reproduction is male pregnancy. Male seahorses aren’t the only animals that put a great deal of effort into raising their young, but they are the only ones that become pregnant, subject to all aspects of the phenomenon—even stretch marks.

The direct transfer of unfertilized eggs from the female into the male’s brood pouch affords him confidence in his paternity. The male nourishes his offspring inside the pouch and maintains a perfect developmental environment. Unlike other animals, where promiscuity is rife, the male seahorse is 100 percent sure that each of the offspring he carries is his own, with no risk of cuckoldry.

This explains the extreme lengths to which male seahorses are willing to go in raising their young. It is certainly in his best interests to raise as many young as possible so that he can pass his genes on to the next generation. Brood sizes vary hugely within the group: larger species can produce more than 1,000 fry in a single clutch, but the smallest pygmy seahorses can give birth to just half a dozen.

Every day, seahorse pairs meet at dawn, dusk, or both, depending on the species, to perform courtship rituals. These critical times allow the bonding pair to synchronize their reproductive cycles, a process that provides the female with the assurance she needs to hydrate their clutch of eggs—a necessary step before they are ready to be transferred to her mate.

Once it has begun, egg hydration is an irreversible process, so it is important for the female to be confident that her partner is willing and able to accept them. If she does not transfer the clutch at the end of the few days’ hydration process, the eggs can foul and damage her reproductive organs. Even without sickness, the wastage of such large amounts of scarce resources can take its toll.

Synchronization is beneficial as it increases the pair’s overall productivity. Pairs that have been forced to switch mates under laboratory conditions have gone on to produce fewer young over the next couple of broods. Monogamy is a more stable and sustainable option in the long-term. Despite many aquarium studies in which seahorses have been offered multiple mates, there has never been a case of a male or a female seahorse re-mating with another individual for the duration of the male’s pregnancy period. Seahorses usually prefer to remain with the same mate for a season, or even a lifetime.

Males shut their brood pouch after mating, since intrusion of saltwater damages the eggs within, and this is thought to prevent males accepting eggs from several females. Moreover, the energy required by a female to produce a new brood is considered to prevent her from re-mating after transferring eggs to her partner. This has led to seahorses forming enduring bonds that can last for life. The true romantics of the ocean, some may never re-mate, even after their long-term partner dies.

Using as little light as I am able to in order to watch the events unfolding before me, I see the rotund pregnant male pygmy seahorse risk his life by releasing his vice-like grasp on the fan-like gorgonian coral to fight the current and swim to where it strikes with most force. There, he reattaches to the gorgonian, and, once he is confident that he has a strong hold, he begins to go into labor.

Just moments before, after a 10-minute swim against the current along the dark and gloomy reef wall, I had arrived at the gorgonian home of my pygmies. I immediately began to seek out each one of the four residents, which I could identify individually by color and size, before beginning observations that I scribbled on A4 waterproof paper.

Early on in my research, peer pressure from my dive guide friends had morphed my rigid scientific-minded nomenclature of the four fish from 1, 2, 3, and 4 to Tom, Dick, Harry, and Josephine. The group’s exploits certainly seemed to warrant proper names. This unusual conjugal situation—Josephine and three males—gave me a unique opportunity to observe whether the fabled seahorse monogamy, one of the fundamental quirks of their reproduction, could endure such temptation.

I discovered a terrible truth: Not all seahorses are the portraits of domestic bliss that we assumed.

The gorgonian coral buzzed with activity soon after my arrival. Tom, with a belly swollen like a miniature basketball, swam out from the little nook he shared with his gorgonian-mates, to an exposed edge of the expanse. Without much ado, he bent over, expelling numerous tiny black specks into the ocean. These specks, of course, were the brood of young that he had been nurturing in his pouch for the past two weeks. Another couple of contractions and the baby seahorses were released into the water. Before being carried off in the current, the babies uncurled to reveal their heritage; they resembled darkened miniature versions of their parents.

After the birth, the newborn seahorses set off on their own and would never see their parents again, instead spending a couple of weeks at the whim of ocean currents before finding a gorgonian coral of their own on which to settle. My research showed that after they find a suitable gorgonian, they need only five days to change their dark free-floating coloration to match their new gorgonian home in color and surface texture.

Tom was visibly drained after the birth. His previously rotund physique heaved with stress and exhaustion, now he was surely the only male in the animal kingdom with stretch marks. This would be the only moment of rest for Tom; his day had just begun.

No sooner had he given birth than he headed back to the little nook where the other three rested. Josephine immediately noticed his return, and side-by-side, the two began an age-old ritual of mirrored movements and quivers. After conveying to Josephine that he had given birth and was receptive to mating, the pair slowly loosened their grip of the gorgonian and hovered above it. They intertwined their tails, holding together their tiny genital openings. Josephine’s belly, swollen with eggs, gradually shrank as she pushed the clutch of unfertilized eggs into Tom’s pouch. His deflated and wrinkled belly became correspondingly plumper as the eggs entered his pouch and he fertilized them, ensuring him certainty over his fatherhood. The pair’s reproductive synchrony, ensured by daily courtship dances, allowed Tom and Josephine to re-mate so soon. Forty-five seconds later, the pair went their separate ways; Tom, presumably, needing a rest.

During my research I discovered a terrible truth: Not all seahorses are the portraits of domestic bliss that we assumed. I regularly found the three males, Tom, Dick, and Harry, involved in brawls.

Seahorse brawling is a surprisingly comedic affair that involves their most prized appendage: the tail. In one skirmish, Dick grasped Tom around the base of his tail and shoved him off the gorgonian while the hapless Tom thrashed around in disapproval. Harry seized the opportunity and grasped Dick around the neck with his tail too. Since both the bigger males were being held, neither wanted to lose face and let go. The tussle lasted a good several minutes, and Tom was left with a sprained tail for days!

Behind these brawls, of course: the lovely Josephine. During my research, the cause of the turmoil became clear. Josephine was mating with both Tom and Dick.

With a gestation period of 12 days, Josephine would mate with one of the males after he gave birth, and then mate with the other six days later, while the first male was only halfway through his pregnancy. Both males were always pregnant, and Josephine was constantly hydrating eggs for them. She conducted twice-daily dances with both males to keep tabs on their due dates.

This is the first time a seahorse has been found to engage in polygamy. In fact, in this case since it was the female mating with two males, it is technically known as “polyandry,” from the Greek meaning “many men.” Poor Harry never did get a second look during my study, being much smaller than the other two males and presumably failing to gain traction in the wrestling matches.

My research required that I next turn my attention to a female-biased ménage à trois. I had already seen that under the circumstances of a male-biased sex ratio, the female (in this case, Josephine) was able to produce clutches of eggs just days apart in order to impregnate two males (Tom and Dick). Subsequently, I was intrigued to find out whether a single male would accept eggs from two females. Luckily, at my study site there was no shortage of pygmies, and I soon found a perfect group: Brad, Jennifer, and Angelina.

Seahorse brawling is a surprisingly comedic affair that involves their most prized appendage.

I spent many hours with the trio, observing and recording their every interaction. I found that Brad and Jennifer shared a core area on one side of the gorgonian, while Angelina slept on the other side of the gorgonian. A “core area” is the protected area of the gorgonian where they carried out their social bonding dances, mated, and slept. Tom, Dick, Harry, and Josephine all slept together in one small core area.

During my research, Brad and Jennifer raised several broods together, but all the while Brad was also flirting with Angelina. Each morning, after bonding dances with Jennifer, Brad would leave their core area and swim directly to the other side of the gorgonian where Angelina bided her time. Angelina and Brad then carried out the same social bonding dances, but they never mated. In the world of pygmy seahorses, it is always best to keep your options open in case something were to happen to a partner. Unlike the pugnacious males, the two females eschewed violence, instead electing cool indifference.

Broadening my search further, I found another group of pygmies along the reef. On a bright red gorgonian, three pairs shared a home. This offered the opportunity to investigate how bonded pairs interacted with each other. Would jealousy feature in a male pygmy seahorse’s behavior when he was happily partnered? Mapping home ranges and recording social interactions led me to conclude that it would not.

On a gorgonian coral as big as a 34-inch television screen, these individuals spent their entire lives confined to an area as small in some cases as three adjoining Post-it Notes, while the largest spanned the area of a double-page spread in a magazine. Males generally used less space than females, which is probably due to the difficulty of traveling when inflated with young.

When happily settled with a single partner, males appeared to pay no attention to other males, even though their home ranges often overlapped. Hunting for prey to fuel their constant egg production and pregnancy is a full-time pursuit, so they searched for and grazed on the miniscule crustaceans that live on the surface of the gorgonian. ![]()

Excerpted from The World Beneath: The Life and Times of Unknown Sea Creatures and Coral Reefs by Richard Smith; published by Apollo Publishers.

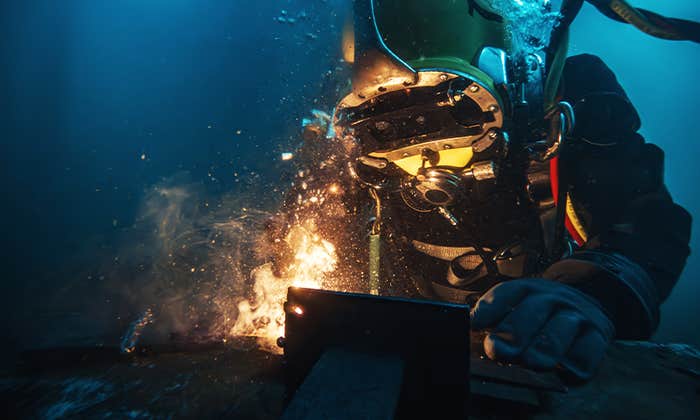

Lead photo: Pair of Bargibant’s pygmy seahorses (Hippocampus bargibanti). South East Sulawesi, Indonesia. © Richard Smith – OceanRealmImages.com