In “Metaphors Are Us,” biologist and neurologist Robert Sapolsky made a good case for why symbolic thinking may be the key feature separating humans from our nearest animal relatives. But that essay didn’t end the discussion, which spilled onto social media and continued there. So Nautilus’ special media editor, Rose Eveleth, solicited questions from readers for Sapolsky via Twitter, and he was good enough to give us these answers:

You

mention that some species do have the beginnings of metaphor—things

like “there’s a predator from the sky, run down.” And in many

ways, all language is metaphoric—using one thing (words/sounds) to

represent another (ideas). So what makes our metaphors particularly

special? What’s the simplest metaphor that we have that chimps or

dolphins might not?

Well,

I’ll make that a little more basic and equate “metaphor” in

this case with “word.” In a certain (well, metaphorical) sense,

many other animals have “words” that are roughly akin to

“I’m angry” or “I’m scared” or “I’m happy.” And

“Yes!” and “No!” Simply means of communicating those

emotional states. Within those confines, maybe the simplest “word”

we have that no animal can come near is “maybe.”

Has

there ever been a case of someone not being able to understand

metaphors due to brain damage? If the frontal cortical region gets

damaged, do you no longer appreciate Shakespeare as much?

Schizophrenia

is very often associated with “concreteness” of thought—an

inability on the part of the sufferer to understand metaphors and

abstractions, to take things more literally than they were meant. And

that is certainly a disease involving brain damage (with us still

knowing woefully little about what precisely that damage is).

How

do we know for sure that animals don’t use or understand metaphors?

That seems like a hard thing to test.

Zoologists

are increasingly sophisticated in their understanding of what animals

can communicate. And with rare exceptions (e.g., the vervet monkey

case discussed in the article), animal communication is about

present-tense, first-person emotional states. Maybe they could

understand metaphors (although that seems vastly unlikely to me,

given what is known about animal cognition), but there’s little

evidence that they communicate anything metaphorically.

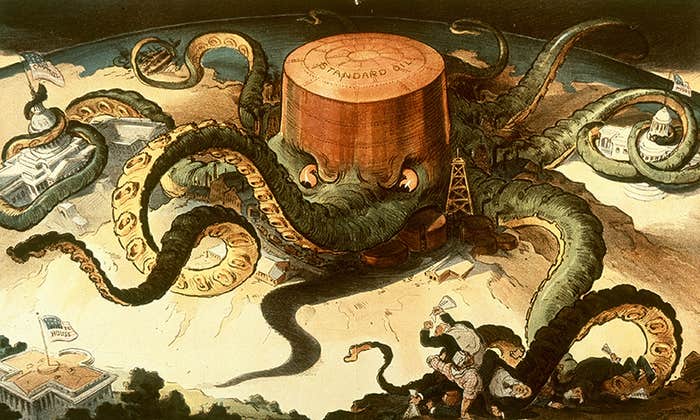

One

commenter pointed out that metaphors can be beautiful things that

communicate poetry or help us understand the plight of someone we’ve

never met. But they can also be dangerous, and send us to war. And

you say at the end that metaphors are double-edged swords, but you

also say that “We can dull the edge that demonizes, and sharpen the

one that urges us to good acts.” How?

Dull

the edge that demonizes: consider the number of genocides that have

been carried out with the victims proclaimed, metaphorically, as

vermin (rats, cockroaches, and so on) and the absurd power that we

are willing to grant to symbols at times. For example, among gangs,

being willing to kill over the color of clothing. By recognizing the

extraordinary power that comes from framing hate in metaphors, we’re

more likely to be able to defang things like that. To not fall for

them as readily.

Sharpening

the edge that urges us to good acts—the flip side of this. The more

we understand how the brain feels the pains of others, the better

we’ll be at fostering empathy and compassion.

Do

we know enough about how our brains process metaphors to design

maximally effective ones, ones that we simply cannot resist?

I

sure hope not…

Why

is it so important to know what it is that makes a human different

from all the other animals?

It

is certainly useful to think about the similarities between us and

other animals (insofar as that prompts us to have a little more

humility as a species). I suppose that one could do some hand-waving

and come up with something useful about thinking about what is unique

about us as a species. Mostly, it just seems to be an irresistibly

interesting thing to think about, simply for it’s own sake.

What’s

your favorite metaphor?

I

have a taste for the classics and history, so, “Loose lips sink

ships.”

Robert Sapolsky is a professor of biology and neurology at Stanford University. He is the author of a number of books, including Why Zebras Don’t Get Ulcers, Monkeyluv, and A Primate’s Memoir.