Two hundred years ago, a small but fierce predator prowled the rocky coasts and islands of Maine. About the size of a housecat, but shaped more like a ferret, the sea mink (Neogale macrodon) denned in crevices between boulders and dove lithely through the frigid ocean, likely hunting for clams, oysters, lobsters, and fish.

The sea mink had coarse, reddish fur, and was at least twice the size of the softer, dark brown American mink—which still stalks the region. This fact would prove to be its undoing. Coveting larger pelts to feed the seemingly unending appetite for fur in Europe, hunters pursued the sea mink with a bloodthirsty zeal. They pried apart rocky ledges with shovels and crowbars to shoot the animals in their hiding spots, or drove them with smoking brimstone and pepper charges from their burrows into the jaws of trained dogs. In 1860, sea mink pelts could be sold for as much as $10 apiece—more than $300 in today’s currency. By 1903, the sea mink had been exterminated.

“We did this only 150 years ago, and it’s been pretty much forgotten in that time,” says Olivia Olson, a graduate student at the University of Maine who is assisting with a project to better understand how the North American fur trade reshaped Maine’s ecosystems. “People forget so quickly what we’ve lost.”

We humans have a relatively short memory for what is “normal” for the natural environment.

Olson grew up in Islesboro, a long, narrow island in Penobscot Bay that sits about two miles from the Maine coast. There, she says, many people view the American mink—the sea mink’s smaller, inland cousin—as a nuisance and an invader. But the American mink may now simply be filling the coastal vacancy left by the sea mink’s extinction.

“We know that sea minks have been on the islands in Maine, and probably Islesboro—it’s not that far from the coast,” Olson says. “American mink are strong swimmers, and sea mink would have been even better.”

We humans have a relatively short memory for what is “normal” for the natural environment—a phenomenon that researchers call shifting baseline syndrome. With each consecutive generation, the idea of a healthy ecosystem changes: People slowly forget the flocks of birds that used to darken the skies or the massive fish that our grandparents pulled from the ocean. By creating a more accurate picture of the past, the researchers and community members involved in Olson’s project, which is led by molecular anthropologist Courtney Hofman at the University of Oklahoma and includes collaborators from several universities, the Smithsonian Institution, and Indigenous tribes, hope to be able to better assess the state of the present and change our perception of what is possible with conservation efforts in the future.

Before the colonial fur trade wiped them out, sea minks coexisted with the native peoples of Maine for generations. The vast majority of existing sea mink bones pre-date European contact, having been unearthed from shell mounds that the ancestors of today’s Wabanaki people created as long as 5,000 years ago. The oyster and clam shells in these mounds contain calcium carbonate, which helps to counteract the natural acidity of Maine’s soils and protect organic material—including sea mink bones—that would otherwise break down.

“Those shells are a preservation agent,” says archaeologist Bonnie Newsom, who is Olson’s advisor and a citizen of the Penobscot Nation, one of the Wabanaki tribes. “Without those, we probably wouldn’t have any evidence of sea mink.”

At one point, these mounds of shells were thought to be little more than trash piles and were raided by 19th-century collectors looking for Native American artifacts to sell to museums. But research from Newson and other archaeologists has shown that there is a deliberate architecture in some of the shell mounds—and that they hold evidence of domestic sites, burials, and ceremonial activities. The sea mink bones found in these places are primarily skull and jaw bones, indicating that the people who made these mounds may have had a specific use or purpose for these parts of the sea mink.

“This species probably had a place in my ancestors’ lives,” Newsom says. “Studying the sea mink will maybe help reveal some of those relationships so that we can better understand our own past.”

In addition to providing insight into Wabanaki history, these bones can help researchers understand how the sea mink used to fit into Maine’s coastal and island ecosystems. Despite its size, the sea mink would have been a significant predator on the coast, and likely an apex predator on many of Maine’s islands—its impressive swimming ability would have allowed it to reach places that were otherwise protected by miles of cold ocean. Its loss would have had ripple effects on the ecosystem, potentially allowing prey populations to grow unchecked or expand to take advantage of new resources. By learning more about the sea mink, researchers hope to decipher the cascade of ecosystem changes caused by its extinction. The answers they find could help determine whether the American mink—which is moving into some of the sea mink’s old territory—is causing new problems or helping to restore a previous balance.

Hofman, who specializes in studying ancient DNA and is the director of the Laboratories of Molecular Anthropology and Microbiome Research in addition to co-directing OU’s Department of Anthropology, is leading the effort to extract DNA from some of the sea mink bones and compare their genome to that of the American mink. By looking at genes that are associated with certain traits in the American mink—color, fur thickness, size, or body fat, for example—Hofman and her colleagues at the Laboratories may be able to learn more about how the sea mink was adapted to the cold, marine environment and what traits set it apart from the American mink.

The researchers are also looking into the sea mink’s diet. Using a technique called stable isotope analysis, they can examine ratios of certain types of carbon or nitrogen in a sea mink’s bones that hint at what the animal may have been eating over the course of its life. The technique can’t identify specific prey species, but it will help differentiate between marine and terrestrial diets, which will indicate where the sea mink spent most of its time hunting.

We did this only 150 years ago, and it’s been pretty much forgotten in that time.

“By going back in time and studying what the sea mink was and how it lived and used resources, we can predict what the impact of American mink in these places might be,” Hofman says.

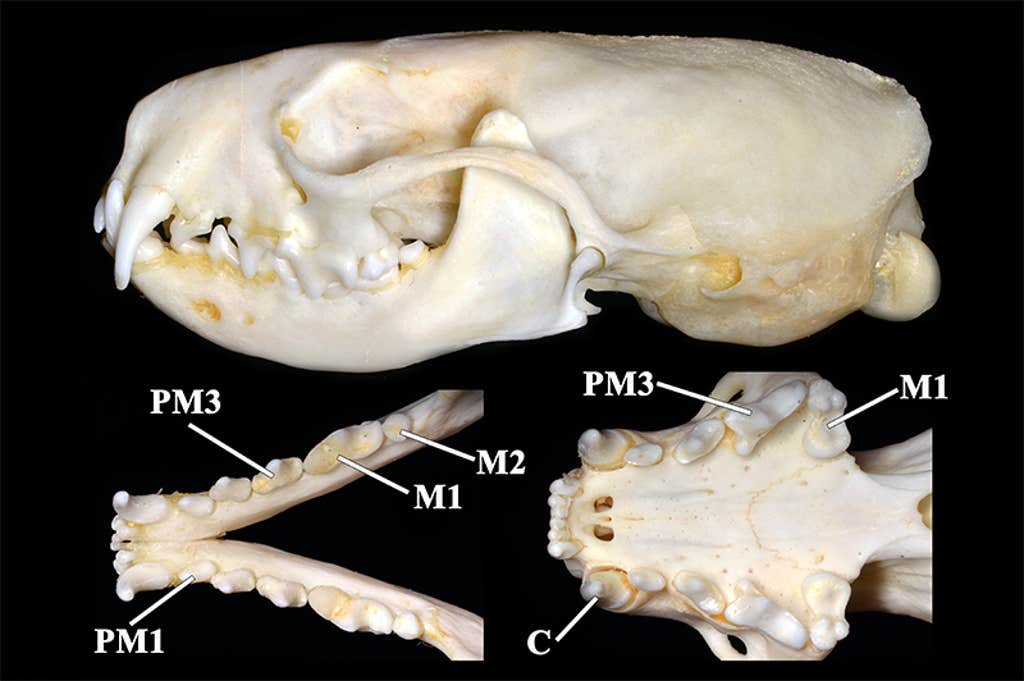

Mustelids—the family of carnivorous mammals that includes mink, otters, weasels, and wolverines—tend to be very adaptable animals. As it has moved into coastal and island environments, the American mink’s diet has adjusted to include more marine prey, such as lobster and fish, as well as seabirds. These may be some of the same prey items that the sea mink used to pursue, though the American mink’s teeth, unlike those of the sea mink, are not adapted to crunch through hard crustacean shells.

Most of the modern samples of American mink that the researchers are using have been donated by Maine’s contemporary trapper community. Unlike the free-for-all approach of the early fur trade, trapping in Maine is now well regulated and restricted to certain months of the year. Many of the trappers are invested in understanding and preserving these populations, and they contribute samples and local knowledge to scientific studies. They have already noticed changes in populations of the American mink that have moved into Maine’s coastal areas.

“Trappers were telling me about their observations—those who have trapped on the coast and inland—and they have noticed that mink are so much bigger out there,” says Shevenell Webb, a furbearer biologist with the Maine Department of Inland Fisheries and Wildlife. Webb thinks that prevalent food and resources on the coast are allowing these animals to grow larger and have more mating success, contributing to their expansion to more of Maine’s islands.

Unfortunately, even if the American mink is able to fill the sea mink’s ecological role, Maine’s coastal ecosystems may have changed too much to support it. Some of Maine’s islands have been free of mink and other predators for decades and provide vital nesting habitat for seabirds, including the federally endangered roseate tern and the state-threatened Arctic tern, razorbill, and Atlantic puffin. The arrival of even a single American mink on a nesting island can have incredibly disruptive effects.

Historically, seabirds likely nested in smaller colonies, spread out over more islands. A mink might kill or drive out the birds on one island, but it would only impact a small percentage of the population. However, because of a variety of factors that include human impacts, an increase in nesting gulls and other avian predators, and regrowth of some island forests, “the birds basically don’t have a lot of options anymore,” says Linda Welch, a wildlife biologist at Maine Coastal Islands National Wildlife Refuge Complex. Most of Maine’s threatened and endangered nesting seabirds are concentrated on only a handful of islands, making it easy for a few predators to do a lot of damage.

“Even if [American mink are] doing the exact same thing as the sea mink, the ecosystem around them has also been changing,” says Alexis Mychajliw, a biologist at Middlebury College who has been helping lead the project. “Conservation isn’t just about going back to a specific point in the past. It’s about everyone coming together with all the different data on hand and doing what they think is best for their community or the species they’re tasked with protecting.”

There is obviously no going back to the pre-colonial conditions of coastal Maine. But understanding where the sea mink fits into our past provides a lens through which we can view our relationship with the American mink and other animals in the future, and will hopefully help us find a new balance that serves Maine’s existing species—humans included—in a changing world. ![]()

Lead image: shauttra / Shutterstock