It’s an all-too-familiar headline: Coral reefs are in crisis. Indeed, in the past 50 years, roughly half of Earth’s coral reefs have died. Coral ecosystems are among the most biodiverse and valuable places on Earth, supporting upward of 860,000 species and a great deal of human well-being—but warming waters are an existential threat. And nowhere are reefs suffering more than in the Caribbean.

After last summer’s unprecedented heat wave, when water temperatures off the coast of Florida exceeded 100 degrees Fahrenheit, coral populations there sank to just 1 percent of their historical abundances. As hard as conservationists have fought to protect corals, they are quickly running out of options.

But what if corals from elsewhere could thrive there?

This question burst into view earlier this year when coral geneticist Mikhail Matz proposed translocating corals from the Pacific Ocean into the Caribbean, setting off a conversation that reverberated far beyond the biology conference where he gave his talk. The idea was picked up by Nature; the BBC called. Matz’s post on X (formerly known as Twitter) about the idea garnered thousands of views.

The proposal diverges radically from conventional conservation practices. Coral conservation in particular has long involved trying to protect them from human insults such as pollution and destructive fishing. As climate change began exacerbating declines, conservationists slowly accepted the practice of coral restoration as well. They started growing local corals in nurseries and replanting them in failing reefs—but even this shift to more active, hands-on strategies reflected a principle that guided earlier approaches. Coral species evolved to live where they are now found; conservation was about preserving those local lineages, not introducing new ones.

Matz, who is based at the University of Texas, Austin, is aware that his proposal to move corals to new waters is a major break with convention. “We don’t want to just plop corals from ocean to ocean,” he says. “We want to develop a good research plan for how we could do it safely and efficiently if it comes to that. We hope it wouldn’t. But that hope is diminishing.”

Because the devil is so often in the details, I sat down with Matz in his office to understand what exactly he was suggesting and why. Matz showed me a graph of global declines. In aggregate the trend is bleak—but when he zoomed in on particular regions, differences emerged.

In the waters between the Philippines, Indonesia, and Palau—called the Coral Triangle and home to the ocean’s most diverse assemblage of coral species—the situation is actually improving. Coral cover, or the proportion of reefs covered in healthy coral, increased from 33 percent in 1983 to 37 percent in 2019. “Corals are still winning the game here,” Matz says.

But in the Caribbean, the forecast is dire. Coral cover has declined from about 35 percent to 16 percent in the same time period. “We’ve lost all these forests, all these jungles,” Matz says, referring to coral thickets that long dominated Caribbean reefs. “The reef is dissolving and being eaten away by parrot fish. And then you add in sea level rise,” which deprives reefs of the light they need to survive.

Corals are still winning the game here.

From about 50,000 years ago until the 1970s reefs were dominated by two species of branching coral, known as elkhorn and staghorn, in the genus Acropora. Today, these species are critically endangered. They also have undergone an extreme physical change. Matz showed me photos of staghorn skeletons collected in the 1700s and in the present. Three hundred years ago, the coral’s branches were as big around as a person’s leg; the typical modern coral’s branches are the size of a finger. Compared to its ancestors, it is unrecognizable.

Adding to their troubles, Caribbean staghorns and elkhorns follow a procreative strategy of growing big, living long, and reproducing when fragments of themselves break off and grow into new colonies. A problem with such asexual reproduction, however, is that it only produces clones, thus foregoing the possibilities that arise from mixing genes. That reduces the corals’ ability to adapt to rapid environmental changes.

Elkhorn and staghorn corals do reproduce sexually as well, but inefficiently. They spawn once per year and broadcast billions of eggs into the sea. Across a coral’s several-hundred-year lifetime, just one or two might be fertilized and survive, a process called recruitment. That worked fine for 50,000 years, but no longer. “Even in the early ’70s and ’80s, these corals were basically extinct,” Matz says. “They have written themselves into a life-history corner from which they are unlikely to recover.”

The Coral Triangle, however, is home to upward of 130 different Acropora species. They have evolved beyond the branching form to include other shapes: plates, arms jutting from a central stem, and fingers extending up from a plate. These corals recruit between 10 and 100 times better than their branching Caribbean cousins. When one hears of reefs recovering in the Indo-Pacific, says Matz, “it’s mostly those plating bushy kind of things. It comes back really, really rapidly—in less than 10 years.”

“So what do we do?” he continued. “We take these super-recruiters and put them in the Caribbean. Because we need those to get resilience back to the reefs, the ability to spring back after being knocked down. Right now, you destroy a Caribbean reef, it stays destroyed.”

It’s impossible to talk about translocating corals without considering the risks. They include—at a minimum—importing diseases and the possibility that Indo-Pacific corals will harm Caribbean animals, either by failing to provide proper habitat or actively competing with local species or disrupting local ecologies in some as-yet-unconsidered way. Matz wants to start studying those risks now, in laboratories and large experimental aquaria. “Let’s not wait until midnight to start planning,” he says. “If push comes to shove, we’ll know how to do it.”

That life history worked fine for 50,000 years, but no longer.

One fear is that transplanted corals could become invasive: proliferating out of control and causing even more harm to Caribbean reefs. By one assessment, invasive species are implicated in 60 percent of global biodiversity losses. The damage wrought by unwittingly translocated creatures, like comb jellies that collapsed anchovy fisheries in the Black Sea in the 1980s, testify to the destructive potential of marine invasions.

There’s a case to be made, though, that intentionally moving species can be done responsibly. An analysis of 125 years of such translocations in the United States found that, when done for conservation purposes, they’ve been overwhelmingly successful. It was translocations done for pest control, trade, or agriculture—without conservation in mind—that caused the majority of the problems.

Lessons have been learned from past mistakes; regulations now require comprehensive risk assessments before species are introduced. Despite perceptions, intentional translocations have “tended to have their intended consequences and not the unintended ones,” says Clare Palmer, a bioethicist at Texas A&M University. “But people always worry about the unintended ones.”

The reefs most at risk from translocation gone wrong are those rare places where Acropora are still healthy and invasive coral could outcompete local colonies. One of the last such reefs is in Tela, Honduras. Yet Antal Börcsök, co-manager of the reef’s marine protected area, would support research into translocation. He says he recognizes that the failures of staghorns and elkhorns elsewhere may one day reach that reef, too.

Moving Indo-Pacific coral to the Caribbean, if it were to happen, wouldn’t only be about the science, or even mostly about the science. It would really be about making the decision to do so.

Ethical arguments may favor trying translocation, says Palmer. Living coral reefs absorb wave energy generated by storms, protecting coastlines from destruction; people depend on reef life for subsistence and livelihoods. In Florida, those benefits are worth billions of dollars each year—and replacing lost coral would also prevent the inestimable suffering of animals for whom reefs are home.

Another key question is who gets to decide, says Irus Braverman, an environmental law scholar and author of Coral Whisperers: Scientists on the Brink. In the U.S., multiple federal and state agencies would weigh in. But should that decision-making be limited to authorities? Braverman insists that the public needs to have a voice. “These are important decisions about our relationship with nature that should be democratized,” she says.

Regulators in the U.S. may solicit public input, but those forums can be hard to access. Also, people at agencies responsible for policy decisions may not be from communities connected to reefs. When Palmer studied proposed translocations of whitebark pines—a northwestern tree threatened by climate change in its present range—farther north, the process involved input from Indigenous people who would be impacted, she says. Similar participation, along with that of other people who live near and work on the reefs, would be critical for coral translocation.

Tiffany Duong lives in the Florida Keys and volunteers with conservation groups who grow and plant native corals to repopulate reefs. She described the arduous work of moving corals from undersea nurseries to aquaria during last summer’s heat wave and said plans are already underway for a larger emergency rescue this summer. Knowing that the corals she helped plant were dying was heartbreaking.

“If enough research was done for each species, so we were certain it wouldn’t screw with the new environment, I’d be baseline okay with it,” Duong says of translocation. “You have to be okay with a shift. Otherwise, you have a waste zone.”

Although Matz’s proposal is radical, it’s not without precedent. In 2003, researchers diving in Jamaica’s Discovery Bay noticed some unusual coral; John Bruno, a coral ecologist at University of North Carolina Chapel Hill, recognized it as an Indo-Pacific species, called a mushroom coral, that shouldn’t have been in the Caribbean at all.

The coral’s origin was a mystery. Originally, it was reported that the corals arrived in 1966 when the director of Discovery Bay’s research station visited the Red Sea, returned with some specimens, and used the reef as a holding tank for them. He died unexpectedly, and the corals were forgotten. Later genetic work, however, suggested the corals had come from a researcher who brought them from Hawaii.

In a comment about the discovery published in 2003, Bruno and his colleagues described how the coral “survived two of the most damaging hurricanes in Jamaican history, the collapse of the native coral population, and subsequent domination of the reef by macroalgae.” Although the new species didn’t appear to be causing problems, “the fact that it has survived in this new environment should be viewed as an ominous warning of potential future invasions.”

Two decades later, Bruno says of Matz’s proposal to move coral from the Indo-Pacific to the Caribbean that “Emotionally, I am against it. And that’s more my philosophical stance as a preservationist. But realistically, given how much we’ve already changed everything and how quickly Caribbean reefs are changing, I think we should talk about this as a potential solution.”

Does Bruno still consider the mushroom coral’s ability to survive in the Caribbean “ominous?” Says Bruno, “I don’t feel like that anymore.” ![]()

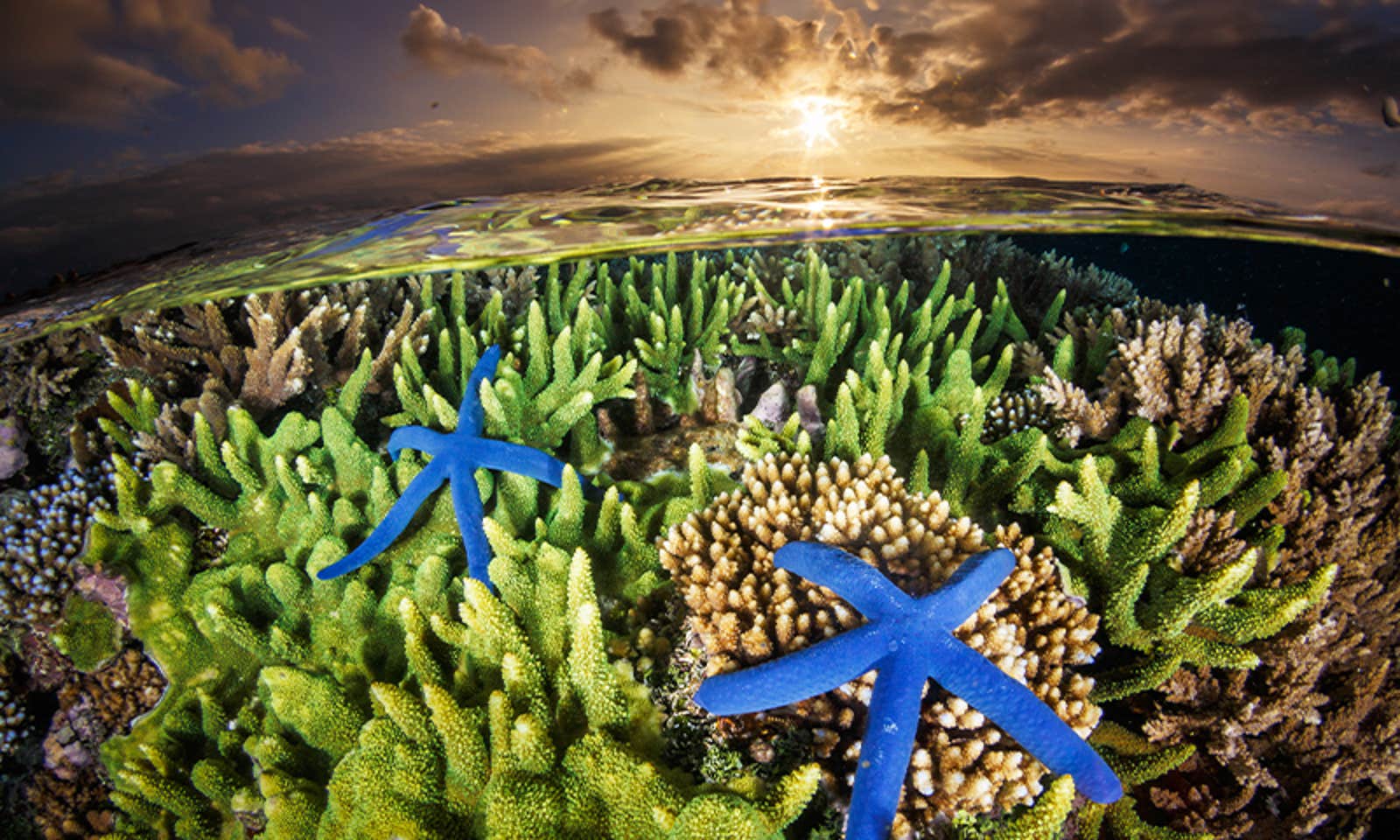

Lead photo by Grant Thomas / Ocean Image Bank