In March, a diet coach named Anthony Gustin, founder of an online food store called Perfect Keto (“Empowering your health journey in a food system that doesn’t care”), went viral on social media. The “clinician” and “food and fitness skeptic,” as he refers to himself on Twitter, tweeted that he had recently traveled to Africa to spend time with the Hadza, a group of foragers in Tanzania, to learn more about living a healthy lifestyle. In a hunting trip set up for tourists, Gustin followed the Hadza as they went about their day, observing how they hunt, socialize, and make their living. In the viral thread, he favorably contrasts these “wild humans” with “chubby, modern humans” living in “manmade zoos.” He calls studies of the Hadza a “LIE” and “mythical.” A photo shows Gustin sitting alongside several Hadza men, appearing pensive. “I hunted, killed, and ate a wild baboon (brains and all) with the indigenous Hadza tribe in Africa,” he tweeted. “Here are 13 things I learned about human health along the way.”

In his tweets, Gustin makes some astonishing observations about the Hadza. They “barely eat any plants” or fiber. “The men dream about big game hunts. Not huge salads or leafy greens.” Both the men and women only work for “3-4 hours a day.” The Hadza create no waste. They rarely rush, stress, or worry. And, believe it or not, they “rarely drink water,” opting instead for a “few sips of mud.” Though “nearly extinct,” the Hadza are still thriving in their “natural habitat.”

As an anthropologist, I’m used to encountering misconceptions about hunter-gatherers in the media. But rarely had I seen such a harmful combination of tropes, inaccuracies, and stereotypes—at least, not from the 21st century. Initially, I didn’t want to reply to the thread for fear of further amplifying it. But as the attention grew and multiplied, I felt compelled to correct the record. I replied to Gustin on Twitter, outlining not only the clear inaccuracies in the thread—the Hadza, for instance, eat an enormous number of plants1—but also explained how his claims had reawakened tropes from the darkest ages of anthropology. Gustin, who now has almost 23,000 followers on Twitter, called me a woke idiot and blocked me.

What Gustin doesn’t seem to realize—and appears to be willfully evading—is how his narrative, and others like it, perpetuate damaging beliefs in the social sciences, beliefs that those in power regularly exploit to further marginalize already precarious populations. Though Gustin seems just aware enough of the Hadza’s struggle over their sovereignty to fashion himself as the hero of their story: “The government was going to eradicate the Hadza’s land,” he says, “until they figured out tourists (like me) would pay to go to Tanzania to see them.”

What does Gustin get wrong about the Hadza and human health? Nearly everything. Gustin seems unaware that what he experienced on a short tour may not be representative of how an entire population lives when he’s not there. Almost every claim about their diet—the lack of fiber, plants, and water—is simply wrong.

Years of careful ethnographic observations and interviews with community members reveal what a short tour cannot: The Hadza have a diverse diet of tubers, berries, meat, baobab, and honey. The relative importance of each fluctuates with the changing seasons.2 Only about 15 percent of community members rely on hunting and gathering, with the majority opting for a predominantly agricultural diet.3 (Digging for tubers, an important fallback food and continuous source of calories, is primarily a task for women and sometimes children, who are conspicuously absent in Gustin’s narrative.)

What about the claim that the Hadza only work several hours a day? Once again, Gustin may be unaware—this time of how far he has tread into a decades-long debate in the field of anthropology. The proposition that hunter-gatherers live a life of leisure can be traced back most notably to anthropologist Marshall Sahlins, who referred to the way foragers live as the “original affluent society.”

Using a sampling of activity data from the !Kung—a forager group living near the Kalahari Desert—Sahlins claimed that hunter-gatherers spent no longer than five hours a day on labor. But he failed to incorporate into his estimates other forms of work, such as food processing and preparation, which upped the estimate significantly. The most recent and rigorous investigation into this question suggests that those in non-industrial societies work full days, laboring somewhere between 46-54 hours a week.4

More pernicious is the way Gustin’s thread caricatures Hadza life as one of “extreme happiness and leisure.” They spend most of their time “laughing, or telling stories,” Gustin says. This whitewashes the true story of the Hadza, which is radically more complex and nuanced. Many members of the Hadzabe, like law student and activist Shani Mangola, regularly speak out against the sort of mischaracterizations Gustin amplifies about his community. “[People] disrespect us and … use abusive language against us,” Shani has tweeted, “as if we [are] not human beings.” And there are plenty of legitimate stressors in their lives. “Land encroachment and environment destruction,” he tweeted, “is [a] huge problem.” He also shares that the Hadza lack enough resources. “We lose hope,” he added, “and [the] future of our kids become[s] hopeless.”

Almost every claim about the Hadza’s diet—the lack of fiber, plants, and water—is wrong.

Beyond the scientific inaccuracies, what compelled me the most to respond to Gustin’s tweets was his framing of the Hadza as an exotic curio, as “wild humans” trapped in the Stone Age. On his personal podcast, Gustin claimed, incorrectly, that the Hadza have “been more-or-less unaffected in their way of life for the last 50,000 years.” They’re a “window into the past,” he said. Gustin’s “adventure buddy” Paul Saladino—proponent of the dubious “Carnivore Diet”—chimed in: “The Hadza are the closest thing we have to a time machine.” Gustin added, “These people want to live like this. They don’t want to transition to a more ‘civilized’ way of life.”

This type of argument is nothing new; it is a recurring motif in the pseudoscientific attempt to characterize human variation. The history of discourse around Indigenous populations has ranged from the explicitly violent to the benevolently racist. A common trope in this genre is that of the Noble Savage, a wild human uncorrupted by the evils of civilization, living in harmony with nature.

This idea is most commonly attributed to Jean-Jacques Rousseau, and has been invoked throughout the centuries as a way to draw distinctions between “civilized” and “primitive” man. It carries with it a deep paternalism, an idea that Indigenous groups are somehow naive, unspoiled, and innocent, in need of protection. The Indigenous are not the authors of their own lives, nor are they given permission to set their own agenda. No, Westerners are here to do that for them. They know better: The Hadza don’t want their culture to be “spoiled by civilization.” Never mind the fact that this means depriving them of the choice to access education, infrastructure, and healthcare.

Gustin may not realize his role in this story, but his ignorance does not absolve him of his complicity. On his podcast, he recounted the moment that his Hadza guide told him and Saladino that they’re welcome back, but they should bring with them more ugali—a food made of maize meal. “In my mind, I thought, ‘I’m not going to bring you ugali!” Gustin said. “‘I’ll bring you more arrowheads!’”

A more overtly malignant stereotype in the history of anthropology is that of the Indigenous as subhuman, on a rung between civilized man and his primate kin. On his podcast, Gustin is careful to note that the Hadza are, in fact, Homo sapiens. (Imagine needing to clarify that.) Yet he goes on to describe them as an “endangered species,” saying, on his podcast, “Without tourism, they would have been wiped out completely by now.”

Gustin notes that the Hadza are, in fact, Homo sapiens. Imagine needing to clarify that.

This type of language—almost exclusively used to describe non-human animals—is dehumanizing, strips these communities of their agency, and sets the stage for persistent discrimination and exploitation. Though Gustin lionizes tourism as the solution to the Hadza’s struggles, it can often have a devastating influence on Indigenous ways of life.

“The Hadza often find the steady flow of tourist arrivals to the settlement in Mang’ola tiresome,” anthropologist Haruna Yatsuka writes in a 2018 report.5 “[They] must strike a precarious balance between their own ways of life and the pressures to perform that way of life in the commodified context of the global tourist economy.” Tourism gives Indigenous people “the impossible task,” argues archaeologist Michael Rowland, “of acting out pre-contact stereotypes of themselves produced by the colonizing culture.”6

The negative effects of the tourist trade on foragers’ lives are well documented. The commodification of Indigenous culture often carries a steep cost. An infamous account comes from the Shuar, a forager-horticulturalist group in Amazonian Ecuador with whom I regularly work. The tourist trade that began in the late 19th century deeply affected their communities. The Shuar would ritually craft tsantsa, or shrunken heads, from the bodies of their fallen enemies. The Western interest in collecting tsantsa—which still line the exhibit halls of places like Ripley’s Believe It or Not—set into motion a sharp rise in war raiding to satisfy the increasing demand of explorers and tourists, a trend which lasted for nearly 100 years and robbed countless lives.

Despite the inaccuracies and stereotypes, Gustin’s thread revealed interest in the insights anthropology can offer about human health. As it happens, biological anthropologists spend decades conducting rigorous and ethical research on these very questions. So, what can biological anthropology say about living healthier?

Let’s begin with diet. Unlike our primate cousins, who have a relatively limited menu of foods to choose from, humans are tremendously flexible omnivores. The ability to thrive on an immense variety of food has helped us inhabit nearly every ecosystem on the planet and devise the cuisines that make up our rich culinary world. It is tempting to think that our bodies are in a state of evolutionary mismatch, such that the cultural and energetic environment has changed too rapidly for our genes to keep up. There is some truth to that, but as with all things anthropological, there is nuance to consider.

A simplistic—and incorrect—understanding of this evolutionary process would lead one to conclude that the best diet is the one that our “caveman” ancestors ate, as if our bodies were in a state of perfect health during the Pleistocene and simply stopped evolving in the following years. This shallow understanding of human evolution is pervasive, and yet it is the flawed foundation on which Gustin builds his argument. The idea that the “correct” diet is an ancient one is also the backbone of fads like the Paleo Diet, and “adventure buddy” Saladino’s Carnivore Diet, which can, as his website claims, take us “back to our ancestral roots.”

When I hear that we “should eat like the humans of the Paleolithic,” my initial response is: Which humans of the Paleolithic? This epoch—which ranges from 2.5 million years ago to around 12,000 years ago—began with Homo erectus in Africa and ended with Homo sapiens everywhere. Which diet, exactly, are we supposed to be following? The Paleolithic Arctic Diet, composed mostly of marine meat? The Paleolithic Amazonian Diet, made of tubers and fish? Or perhaps, as Gustin and Saladino claim, we should order from the Hadza menu of baboon and honey.

So, what can biological anthropology say about living healthier?

While there is no single “correct” diet to emulate from the past, we can gain some insights by considering how human physiology varies from that of other primates. The patterning of our teeth—a combination of flesh-ripping incisors and fiber-grinding molars—are suited for an omnivorous diet of both animal meat and plant foods. The reduced size of our gut and the way our digestive system processes food supports the same conclusion. This does not mean that we should eat both animals and plants; that would be committing the naturalistic fallacy (just because something is found in nature, does not imply it must be good, or moral).

We can also pool data from extant foraging communities and look for similarities and differences. Here, however, there are far more differences than similarities. As anthropologist Herman Pontzer, who has worked with the Hadza for several years, states in a 2018 paper with his colleagues, “Dietary diversity among hunter-gatherers is so vast that dietary universals are few.”7

A handful of similarities remain. Work by anthropologist Melvin Konner suggests that the diets of those in foraging societies are markedly lower in sodium and refined carbohydrates, and much higher in fiber and protein, than those of folks in industrialized settings.8 Plus, all human groups cook their food, and that food is always a mix of both plants and animals. Beyond that, dietary diversity is the norm, and the data here suggest, as Katharine Milton argues, “that humans can thrive on extreme diets as long as these diets contribute the full range of essential nutrients.”9 These include macronutrients—things like carbohydrates, fats, water, and protein—and micronutrients, like vitamins. A person eating a diet rich in vegetables, fruits, and lean proteins will almost certainly have everything they need. “The range of ‘natural’ human diets is vast,” Pontzer writes in his book Burn. “People eat whatever is available.”

What about exercise? Surprisingly, the Hadza do not appear to be expending more energy than more sedentary and industrialized populations. That’s strange, because accelerometry data—collected through devices that measure steps—suggest that the Hadza are extremely physically active: Women are walking an average of nearly 4 miles a day, while the men regularly walk double that.7 And yet their measures of total energy expenditure—the number of kilocalories they burn in a day—are virtually identical to those of sedentary Americans.

In a 2017 Scientific American article, Pontzer writes, “It seems so obvious and inescapable that physically active people burn more calories that we accept this paradigm without much critical reflection or experimental evidence.”10 But what experiments reveal instead is a fascinating fact about human health: Our bodies adjust to higher activity levels and put a cap on the number of calories we burn each day. How? By taking away energy from other physiological tasks, like cell maintenance, and freeing those calories up for physical activity.11

This research has consequences for how we think about conditions like obesity. It has long been believed that the obesity epidemic is a result of both higher caloric intake and a sedentary lifestyle. And many people believe that weight loss is best achieved through diet and exercise. It’s widely assumed that a calorie in is equivalent to a calorie out. Just treat it like arithmetic: Eat less than you burn. But it appears our bodies don’t follow this rule so rigidly; they don’t like to spend more than a certain number of calories a day and are willing to turn down functions, like cell maintenance, to do it. Perhaps the focus, then, should be less on burning energy through physical activity, and more on reducing the energy we take in through food. “The Hadza don’t develop obesity and metabolic disease for the simple reason that their food environment doesn’t drive them to overconsume,” Pontzer writes in Burn. “The Hadza [showed us] a new way of understanding ourselves.”

On Gustin’s website, he states that when he “started to learn more about science,” he became “enamored with the thought of modifying diet and exercise.” Who can fault that? Science can inspire us to pursue any number of passions. But it is important to recognize that it is imperfect. Anthropology in particular has been fraught with centuries of racism, colonialism, and imperialism, the effects of which still echo into the present and color how people talk about human variation. But like science more broadly, anthropology is self-correcting. My friends and colleagues in anthropology care deeply about the people with whom they work, the people who invite them into their homes and communities.

Some of them are working to redefine what ethical cross-cultural research looks like in the 21st century, paying attention to the impact their research can have on vulnerable populations. In a 2020 paper, for example, anthropologist Alyssa Crittenden and her colleagues write, “The growing appetite for including diverse populations in work on demography, health, wealth, cooperation, cognition, infant and child development, and belief systems raises unique scientific and ethical issues, independent of discipline or research topic.”12 Crittenden has also supported the founding of the Olanakwe Community Fund, a mutual-aid organization created by the Hadza, based on a strong desire among the community for greater access to educational opportunities and a seat at the political table. She is not alone in these endeavors.

I am intimately familiar with the joy of learning about humanity; I have built my career on it. And I see that same curiosity in others, eager to learn more about the human story and their role in it. We share this in common, along with the thousands of other quirks and nuances that make us human. Scientists and the public have a symbiotic relationship: The public supports our work, through grants, tuition, and their attention, and in return, we owe them the spoils of our research, helping to guide their thinking on what it means to be human. And sometimes that means setting the record straight on Twitter. ![]()

Dorsa Amir is an evolutionary anthropologist and postdoctoral research fellow at U.C. Berkeley. Follow her on Twitter @DorsaAmir.

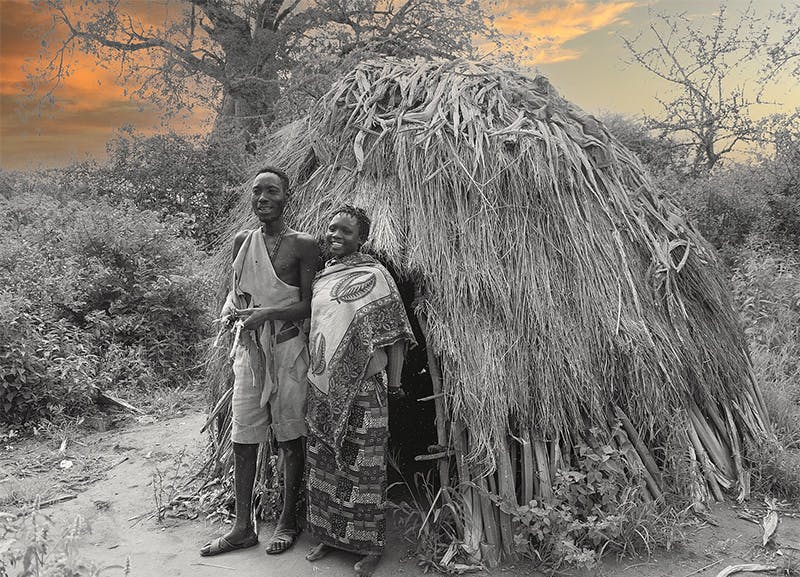

Lead photo: Marzolino / Shutterstock

References

1. Marlowe, F.W., et al. Honey, Hadza, hunter-gatherers, and human evolution. Journal of Human Evolution 71, 119-128 (2014).

2. Marlowe, F.W., & Berbesque, J.C. Tubers as fallback foods and their impact on Hadza hunter-gatherers. American Journal of Physical Anthropology 140, 751-758 (2009).

3. Pollum, T.R., Herlosky, K.N., Mabulla, I.A., & Crittendon, A.N. Changes in juvenile foraging behavior among the Hadza of Tanzania during early transition to a mixed-subsistence economy. Human Nature 31, 123-140 (2020).

4. Bhui, R., Chudek, M., & Henrich, J. Work time and market integration in the original affluent society. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 116, 22100-22105 (2019).

5. Yatsuka, H. Sustainable hunting as commodity: The case of Tanzania’s Hadza hunter-gatherers. Globe Journal 11 (2018).

6. Rowland, M.J. Return of the ‘noble savage’: Misrepresenting the past, present and future. Australian Aboriginal Studies (2004).

7. Pontzer, H., Wood, B.M., & Raichlen, D.A. Hunter-gatherers as models in public health. Obesity Reviews 19, 24-35 (2018).

8. Konner, M., & Eaton, S.B. Paleolithic nutrition: Twenty-five years later. Nutrition in Clinical Practice 25, 594-602 (2010).

9. Milton, K. Hunter-gatherer diets—a different perspective. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 71, 665-667 (2000).

10. Pontzer, H. The exercise paradox. Scientific American Special Editions 27, (2017).

11. Pontzer, H., et al. Constrained total energy expenditure and metabolic adaptation to physical activity in adult humans. Current Biology 26, 410–417 (2016).

12. Broesch, T., et al. Navigating cross-cultural research: Methodological and ethical considerations. Proceedings of the Royal Academy B 287 202001245 (2020).