Philosopher Shannon Vallor and I are in the British Library in London, home to 170 million items—books, recordings, newspapers, manuscripts, maps. In other words, we’re talking in the kind of place where today’s artificial intelligence chatbots like ChatGPT come to feed.

Sitting on the library's café balcony, we are literally in the shadow of the Crick Institute, the biomedical research hub where the innermost mechanisms of the human body are studied. If we were to throw a stone from here across St. Pancras railway station, we might hit the London headquarters of Google, the company for which Vallor worked as an AI ethicist before moving to Scotland to head the Center for Technomoral Futures at the University of Edinburgh.

Here, wedged between the mysteries of the human, the embedded cognitive riches of human language, and the brash swagger of commercial AI, Vallor is helping me make sense of it all. Will AI solve all our problems, or will it make us obsolete, perhaps to the point of extinction? Both possibilities have engendered hyperventilating headlines. Vallor has little time for either.

She acknowledges the tremendous potential of AI to be both beneficial and destructive, but she thinks the real danger lies elsewhere. As she explains in her 2024 book The AI Mirror, both the starry-eyed notion that AI thinks like us and the paranoid fantasy that it will manifest as a malevolent dictator, assert a fictitious kinship with humans at the cost of creating a naïve and toxic view of how our own minds work. It’s a view that could encourage us to relinquish our agency and forego our wisdom in deference to the machines.

It’s easy to assert kinship between machines and humans when humans are seen as mindless machines.

Reading The AI Mirror I was struck by Vallor’s determination to probe more deeply than the usual litany of concerns about AI: privacy, misinformation, and so forth. Her book is really a discourse on the relation of human and machine, raising the alarm on how the tech industry propagates a debased version of what we are, one that reimagines the human in the guise of a soft, wet computer.

If that sounds dour, Vallor most certainly isn’t. She wears lightly the deep insight gained from seeing the industry from the inside, coupled to a grounding in the philosophy of science and technology. She is no crusader against the commerce of AI, speaking warmly of her time at Google while laughing at some of the absurdities of Silicon Valley. But the moral and intellectual clarity and integrity she brings to the issues could hardly offer a greater contrast to the superficial, callow swagger typical of the proverbial tech bros.

“We’re at a moment in history when we need to rebuild our confidence in the capabilities of humans to reason wisely, to make collective decisions,” Vallor tells me. “We’re not going to deal with the climate emergency or the fracturing of the foundations of democracy unless we can reassert a confidence in human thinking and judgment. And everything in the AI world is working against that.”

AI As a Mirror

To understand AI algorithms, Vallor argues we should not regard them as minds. “We’ve been trained over a century by science fiction and cultural visions of AI to expect that when it arrives, it’s going to be a machine mind,” she tells me. “But what we have is something quite different in nature, structure, and function.”

Rather, we should imagine AI as a mirror, which doesn’t duplicate the thing it reflects. “When you go into the bathroom to brush your teeth, you know there isn’t a second face looking back at you,” Vallor says. “That’s just a reflection of a face, and it has very different properties. It doesn’t have warmth; it doesn’t have depth.” Similarly, a reflection of a mind is not a mind. AI chatbots and image generators based on large language models are mere mirrors of human performance. “With ChatGPT, the output you see is a reflection of human intelligence, our creative preferences, our coding expertise, our voices—whatever we put in.”

Even experts, Vallor says, get fooled inside this hall of mirrors. Geoffrey Hinton, the computer scientist who shared this year’s Nobel Prize in physics for his pioneering work in developing the deep-learning techniques that made LLMs possible, at an AI conference in 2024 that “we understand language in much the same way as these large language models.”

Hinton is convinced these forms of AI don’t just blindly regurgitate text in patterns that seem meaningful to us; they develop some sense of the meaning of words and concepts themselves. An LLM is trained by allowing it to adjust the connections in its neural network until it reliably gives good answers, a process that Hinton compared to “parenting for a supernaturally precocious child.” But because AI can “know” vastly more than we can, and “thinks” much faster, Hinton concludes that it might ultimately supplant us: “It’s quite conceivable that humanity is just a passing phase in the evolution of intelligence,” he said at a 2023 MIT Technology Review conference.

“Hinton is so far out over his skis when he starts talking about knowledge and experience,” Vallor says. “We know that the brain and a machine-learning model are only superficially analogous in their structure and function. In terms of what’s happening at the physical level, there’s a gulf of difference that we have every reason to think makes a difference.” There’s no real kinship at all.

I agree that apocalyptic claims have been given far too much airtime, I say to Vallor. But some researchers say LLMs are getting more “cognitive”: OpenAI’s latest chatbot, model o1, is said to work via a series of chain-of-reason steps (even though the company won’t disclose them, so we can’t know if they resemble human reasoning). And AI surely does have features that can be considered aspects of mind, such as memory and learning. Computer scientist Melanie Mitchell and complexity theorist David Krakauer have proposed that, while we shouldn’t regard these systems as minds like ours, they might be considered minds of a quite different, unfamiliar variety.

“I’m quite skeptical about that approach. It might be appropriate in the future, and I’m not opposed in principle to the idea that we might build machine minds. I just don’t think that’s what we’re doing right now.”

Vallor’s resistance to the idea of AI as a mind stems from her background in philosophy, where mindedness tends to be rooted in experience: precisely what today’s AI does not have. As a result, she says, it isn’t appropriate to speak of these machines as thinking.

Her view collides with the 1950 paper by British mathematician and computer pioneer Alan Turing, “Computing machinery and Intelligence,” often regarded as the conceptual foundation of AI. Turing asked the question: “Can machines think?”—only to replace it with what he considered to be a better question, which was whether we might develop machines that could give responses to questions we’d be unable to distinguish from those of humans. This was Turing’s “Imitation Game,” now commonly known as the Turing test.

But imitation is all it is, Vallor says. “For me, thinking is a specific and rather unique set of experiences we have. Thinking without experience is like water without the hydrogen—you’ve taken something out that loses its identity.”

Reasoning requires concepts, Vallor says, and LLMs don’t truly develop those. “Whatever we’re calling concepts in an LLM are actually something different. It’s a statistical mapping of associations in a high-dimensional mathematical vector space. Through this representation, the model can get a line of sight to the solution that is more efficient than a random search. But that’s not how we think.”

They are, however, very good at pretending to reason. “We can ask the model, ‘How did you come to that conclusion?’ and it just bullshits a whole chain of thought that, if you press on it, will collapse into nonsense very quickly. That tells you that it wasn’t a train of thought that the machine followed and is committed to. It’s just another probabilistic distribution of reason-like shapes that are appropriately matched with the output that it generated. It’s entirely post hoc.”

Against the Human Machine

The pitfall of insisting on a fictitious kinship between the human mind and the machine can be discerned since the earliest days of AI in the 1950s. And here’s what worries me most about it, I tell Vallor. It’s not so much because the capabilities of the AI systems are being overestimated in the comparison, but because the way the human brain works is being so diminished by it.

“That’s my biggest concern,” she agrees. Every time she gives a talk pointing out that AI algorithms are not really minds, Vallor says, “I’ll have someone in the audience come up to me and say, ‘Well, you’re right but only because at the end of the day our minds aren’t doing these things either—we’re not really rational, we’re not really responsible for what we believe, we’re just predictive machines spitting out the words that people expect, we’re just matching patterns, we’re just doing what an LLM is doing.’”

Hinton has suggested an LLM can have feelings. “Maybe not exactly as we do but in a slightly different sense,” Vallor says. “And then you realize he’s only done that by stripping the concept of emotion from anything that is humanly experienced and turning it into a behaviorist reaction. It’s taking the most reductive 20th-century theories of the human mind as baseline truth. From there it becomes very easy to assert kinship between machines and humans because you’ve already turned the human into a mindless machine.”

It’s with the much-vaunted notion of artificial general intelligence (AGI) that these problems start to become acute. AGI is often defined as a machine intelligence that can perform any intelligent function that humans can, but better. Some believe we are already on that threshold. Except that, to make such claims, we must redefine human intelligence as a subset of what we do.

“Yes, and that’s a very deliberate strategy to draw attention away from the fact that we haven’t made AGI and we’re nowhere near it,” Vallor says.

Silicon Valley culture has the features of religion. It’s unshakeable by counterevidence or argument.

Originally, AGI meant something that misses nothing of what a human mind could do—something about which we’d have no doubt that it is thinking and understanding the world. But in The AI Mirror, Vallor explains that experts such as Hinton and Sam Altman, CEO of OpenAI, the company that created ChatGPT, now define AGI as a system that is equal to or better than humans at calculation, prediction, modeling, production, and problem-solving.

“In effect,” Vallor says, Altman “moved the goalposts and said that what we mean by AGI is a machine that can in effect do all of the economically valuable tasks that humans do.” It’s a common view in the community. Mustafa Suleyman, CEO of Microsoft AI, has written the ultimate objective of AI is to “distill the essence of what makes us humans so productive and capable into software, into an algorithm,” which he considers equivalent to being able to “replicate the very thing that makes us unique as a species, our intelligence.”

When she saw Altman’s reframing of AGI, Vallor says, “I had to shut the laptop and stare into space for half an hour. Now all we have for the target of AGI is something that your boss can replace you with. It can be as mindless as a toaster, as long as it can do your work. And that’s what LLMs are—they are mindless toasters that do a lot of cognitive labor without thinking.”

I probe this point with Vallor. After all, having AIs that can beat us at chess is one thing—but now we have algorithms that write convincing prose, have engaging chats, make music that fools some into thinking it was made by humans. Sure, these systems can be rather limited and bland—but aren’t they encroaching ever more on tasks we might view as uniquely human?

“That’s where the mirror metaphor becomes helpful,” she says. “A mirror image can dance. A good enough mirror can show you the aspects of yourself that are deeply human, but not the inner experience of them—just the performance.” With AI art, she adds, “The important thing is to realize there’s nothing on the other side participating in this communication.”

What confuses us is we can feel emotions in response to an AI-generated “work of art.” But this isn’t surprising because the machine is reflecting back permutations of the patterns that humans have made: Chopin-like music, Shakespeare-like prose. And the emotional response isn’t somehow encoded in the stimulus but is constructed in our own minds: Engagement with art is far less passive than we tend to imagine.

But it’s not just about art. “We are meaning-makers and meaning-inventors, and that’s partly what gives us our personal, creative, political freedoms,” Vallor says. “We’re not locked into the patterns we’ve ingested but can rearrange them in new shapes. We do that when we assert new moral claims in the world. But these machines just recirculate the same patterns and shapes with slight statistical variations. They do not have the capacity to make meaning. That’s fundamentally the gulf that prevents us being justified in claiming real kinship with them."

The Problem of Silicon Valley

I ask Vallor whether some of these misconceptions and misdirection about AI are rooted in the nature of the tech community itself—in its narrowness of training and culture, its lack of diversity.

She sighs. “Having lived in the San Francisco Bay Area for most of my life and having worked in tech, I can tell you the influence of that culture is profound, and it’s not just a particular cultural outlook, it has features of a religion. There are certain commitments in that way of thinking that are unshakeable by any kind of counterevidence or argument.” In fact, providing counterevidence just gets you excluded from the conversation, Vallor says. “It’s a very narrow conception of what intelligence is, driven by a very narrow profile of values where efficiency and a kind of winner-takes-all domination are the highest values of any intelligent creature to pursue.”

But this efficiency, Vallor continues, “is never defined with any reference to any higher value, which always slays me. Because I could be the most efficient at burning down every house on the planet, and no one would say, ‘Yay Shannon, you are the most efficient pyromaniac we have ever seen! Good on you!’”

People really think the sun is setting on human decision-making. That’s terrifying to me.

In Silicon Valley, efficiency is an end in itself. “It’s about achieving a situation where the problem is solved and there’s no more friction, no more ambiguity, nothing left unsaid or undone, you’ve dominated the problem and it’s gone and all there is left is your perfect shining solution. It is this ideology of intelligence as a thing that wants to remove the business of thinking.”

Vallor tells me she once tried to explain to an AGI leader that there’s no mathematical solution to the problem of justice. “I told him the nature of justice is we have conflicting values and interests that cannot be made commensurable on a single scale, and that the work of human deliberation and negotiation and appeal is essential. And he told me, ‘I think that just means you’re bad at math.’ What do you say to that? It becomes two worldviews that don’t intersect. You’re speaking to two very different conceptions of reality.”

The Real Danger

Vallor doesn’t underestimate the threats that ever-more powerful AI presents to our societies, from our privacy to misinformation and political stability. But her real worry right now is what AI is doing to our notion of ourselves.

“I think AI is posing a fairly imminent threat to the existential significance of human life,” Vallor says. “Through its automation of our thinking practices, and through the narrative that’s being created around it, AI is undermining our sense of ourselves as responsible and free intelligences in the world. You can find that in authoritarian rhetoric that wishes to justify the deprivation of humans to govern themselves. That story has had new life breathed into it by AI.”

Worse, she says, this narrative is presented as an objective, neutral, politically detached story: It’s just science. “You get these people who really think that the time of human agency has ended, the sun is setting on human decision-making—and that that’s a good thing and is simply scientific fact. That’s terrifying to me. We’re told that what’s next is that AGI is going to build something better. And I do think you have very cynical people who believe this is true and are taking a kind of religious comfort in the belief that they are shepherding into existence our machine successors.”

Vallor doesn’t want AI to come to a halt. She says it really could help to solve some of the serious problems we face. “There are still huge applications of AI in medicine, in the energy sector, in agriculture. I want it to continue to advance in ways that are wisely selected and steered and governed.”

That’s why a backlash against it, however understandable, could be a problem in the long run. “I see lots of people turning against AI,” Vallor says. “It’s becoming a powerful hatred in many creative circles. Those communities were much more balanced in their attitudes about three years ago, when LLMs and image models started coming out. There were a lot of people saying, ‘This is kind of cool.’ But the approach by the AI industry to the rights and agency of creators has been so exploitative that you now see creatives saying, ‘Fuck AI and everyone attached to it, don’t let it anywhere near our creative work.’ I worry about this reactive attitude to the most harmful forms of AI spreading to a general distrust of it as a path to solving any kind of problem.”

While Vallor still wants to promote AI, “I find myself very often in the camp of the people who are turning angrily against it for reasons that are entirely legitimate,” she says. That divide, she admits, becomes part of an “artificial separation people often cling to between humanity and technology.” Such a distinction, she says, “is potentially quite damaging, because technology is fundamental to our identity. We’ve been technological creatures since before we were Homo sapiens. Tools have been instruments of our liberation, of creation, of better ways of caring for one another and other life on this planet, and I don’t want to let that go, to enforce this artificial divide of humanity versus the machines. Technology at its core can be as humane an activity as anything can be. We’ve just lost that connection.” ![]()

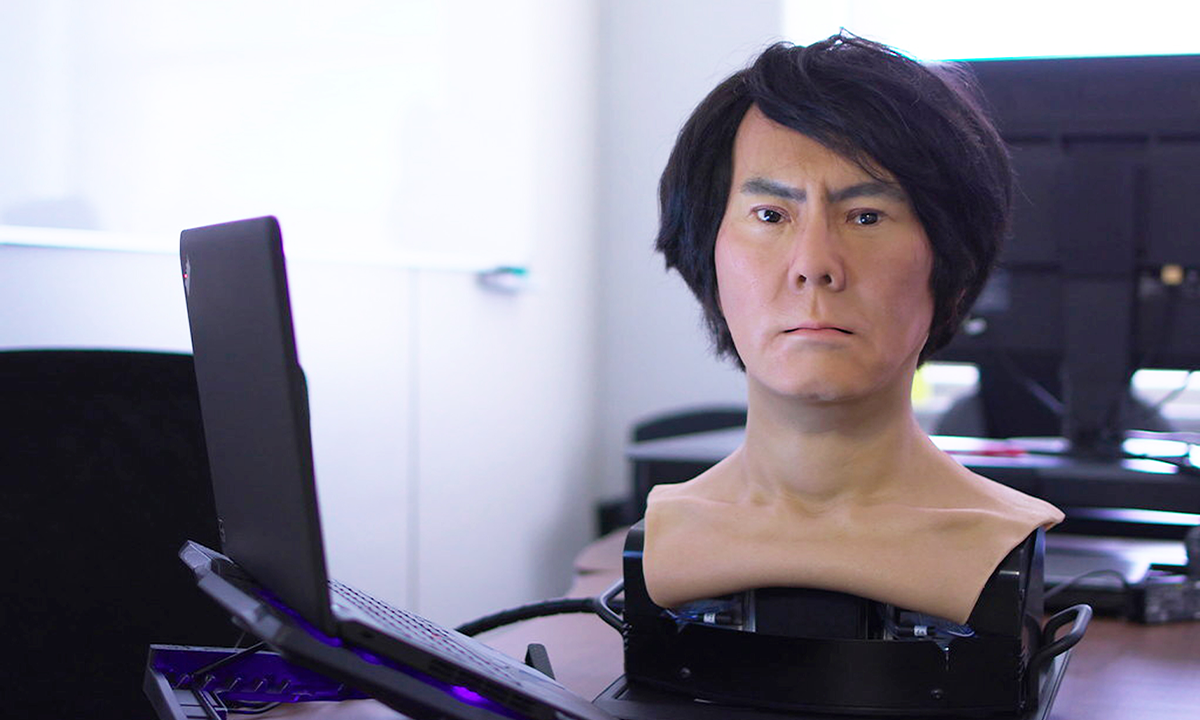

Lead image by Tasnuva Elahi; with images by Malte Mueller / fstop Images and Valery Brozhinsky / Shutterstock