The stories have become all too familiar in Japan, though people often do their best to ignore them. An elderly or middle-aged person, usually a man, is found dead, at home in his apartment, frequently right in his bed. It has been days, weeks, or even months since he has had contact with another human being. Often the discovery is made by a landlord frustrated at not receiving a rent payment or a neighbor who notices an unpleasant smell. The deceased has almost no connections with the world around him: no job, no relationships with neighbors, no spouse or children who care to be in contact. He has little desire to take care of his home, his relationships, his health. “The majority of lonely deaths are people who are kind of messy,” Taichi Yoshida, who runs a moving company that often cleans out apartments where people are discovered long after they die, told Time magazine. “It’s the person who, when they take something out, they don’t put it back; when something breaks, they don’t fix it; when a relationship falls apart, they don’t repair it.”

These lonely deaths are called kodokushi. Each one passes without much notice, but the phenomenon is frequent enough to be widely known. The Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare reported there were 3,700 “unaccompanied deaths” in Japan in 2013, but some researchers estimate that because of significant under-counting, the true figure is closer to 30,000. In any case, the frequency of kodokushi has been on the rise since they emerged in the 1980s.

The increase seems to be associated with deep social changes in the country, particularly the breakdown of the traditional multigenerational Japanese family. In 1960, about 80 percent of elderly Japanese lived with a child; since then that number has split in half. Combined with the fast, well-known aging of the population—today about one in five Japanese people is over 65; that number is projected to grow to one in three by 2030—that leaves a lot of seniors adrift. Already almost a quarter of Japanese men and a tenth of Japanese women over age 60 say there is not a single person they could rely on in difficult times. “It’s like a microcosm of the aging society in Japan,” says a Japanese official. “It’s something no one had anticipated a decade ago.”

The country’s 25-year-long economic doldrums is also a factor. Many men have lost jobs, been forced to retire early, or faced other financial problems, depressing their social standing and making it harder just to get by. Money woes are particularly hard for the generation of Japanese men who came of age when the economy was booming, who invested so much of themselves in their work, forsaking the personal relationships, even with their own children, that could otherwise keep them engaged as they age. “Their world has evaporated under their feet,” says Scott North, a sociologist at Osaka University who studies Japanese work life. “The firm has been everything for these men. Their sense of manliness, their social position, their sense of self is all rooted in the corporate structure.”

In many ways, kodokushi seems to be specifically Japanese. It’s afflicting a society simultaneously coping with significant change in family structure and a generation-long economic slump. Japanese people in sad isolation may feel limited by gaman, the ideal of suffering through tough times without complaint, keeping a stiff upper lip. Similarly, the society has traditionally rejected the American trend toward medicalizing mental illness and mood disorders, spurning talk therapy and antidepressants long after they became commonplace in the West. Many lonely seniors never reach out for help or connection.

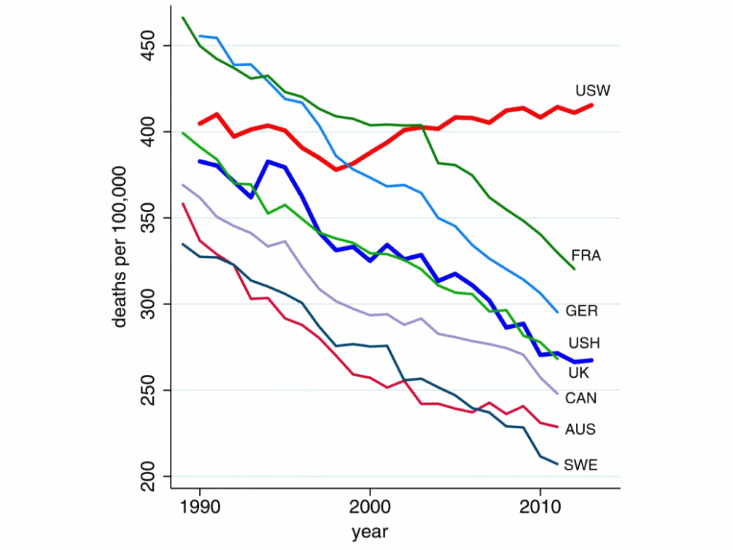

But the increase in deaths of despair may not be unique to Japan. In November of last year, Nobel Prize–winning economist Angus Deaton and Anne Case reported a reversal in one of the most reliable and reassuring trends in modern public health: A big slice of the American populace was dying faster than expected. Deaton and Case, a pair of Princeton economists who happen to be married to each other, specifically found that the mortality rate for white people aged 45–54 without a college education had increased dramatically between 1999 and 2013. The increase ran counter to all recent historical precedent, and it contrasted with concurrent decreases among black and Hispanic people in the U.S. and nationwide decreases in all other rich countries. “Half a million people are dead who should not be dead,” Deaton told the Washington Post. “About 40 times the Ebola stats. You’re getting up there with [deaths from] HIV-AIDS.” Deaton said the increase is so contrary to longstanding trends that demographers’ first reaction would be to say, “‘You’ve got to have made a mistake. That cannot possibly be true.’”

Deaton and Case’s report was soon followed up by another that came to a similar but even broader conclusion. The New York Times analyzed over 60 million death certificates collected by the CDC and found that the mortality rates for all white people between the ages of 25 and 54 had increased since 1999—not only the smaller demographic that Deaton and Case had studied. The study found that the death rate was increasing particularly quickly for white women.

As for why we’re seeing this unexpected increase in mortality, Deaton said, “Drugs and alcohol, and suicide . . . are clearly the proximate cause.” The drugs include the widely reported epidemics of abuse of both heroin and prescription opioid painkillers like oxycodone, both opioids. But behind the epidemic of drug abuse, according to many experts, are economic challenges and weak community and personal bonds. “On a range of social and economic indicators, middle-aged whites have been falling behind in the 21st century,” wrote the authors of yet another recent study that came to a similar conclusion. Health is declining and death rates increasing among less-educated white people because of their “disengagement from the mainstream economy; declining levels of social connectedness; weakened communal institutions; and the splintering of society along class, geographic, and cultural lines,” they wrote.

Looked at that way, the American crisis may not be so dissimilar from the Japanese one. People in each nation are facing social and economic challenges that may be somewhat beyond their abilities to handle. They try to cope in different ways, depending on their personal and cultural backgrounds, and they fail in distinctive ways, as well. Too often, we find out about their struggles with despair only after their sad deaths.

Amos Zeeberg is a freelance science journalist soon relocating to Tokyo. Follow him on Twitter @settostun.

The edited lead photograph is courtesy of Trung Kaching via Flickr.