It’s

easy to think of our cells’ inner workings as parts in a well-oiled

machine—like tiny crankshafts and gears they chug along in their

endless task of transcribing information from DNA, manufacturing

proteins, and sending them off to transact the business of living.

Much

popular writing about cell biology emphasizes the exquisite precision

of this process, and not unfairly; these minute workings can seem far

more exact than the human scale where we stub toes and struggle to

assemble IKEA furniture. The fact that cells have proofreaders,

proteins that skim along freshly made DNA checking for and removing

errors, only adds to the impression of fierce efficiency. But cells

are evolved structures, born from mess, and they are not always as

tidy, as certain, as we expect.

Despite

the proofreaders, errors do creep in during DNA replication, and the

resulting mutations can cause diseases like cancer. Yet messiness can

sometimes be helpful for species in the long run, and likely

contributed to the shape of life today. Imagine that while making new copies of its DNA, a cell slips up: It

puts in a C base where there should be a G base, and the error is

passed down into the cell’s offspring; if the error happens in a

sperm or egg cell, it goes to the offspring of the organism of which they are

a part. This error could be disastrous—perhaps that C makes the

difference between a normally functioning enzyme and one that works

not at all. Or it could be neutral, meaning that not very much

changes. In a very few cases, the enzyme might work better than

before. When that happens, an organism bearing that mistake—that

mutation—may creep ahead of its cohort. Maybe it survives a

disaster thanks to better efficiency from that enzyme, and over time,

the new mutation spreads through the gene pool. Even if the mutation

changes things very little, chance could spread it throughout a

population, through a process called genetic drift. “The

role of stochastic events (survival of the luckiest) is sometimes

hard to distinguish from the role of optimization (survival of the

fittest),” wrote

biologist Dan Tawfik several years ago.

Scientists

aren’t exactly sure how many new mutations crop up each generation

in humans—for years, the standard estimate was round 100-200, but

one 2011 study,

using whole genome information from two families, has put it at about 30–50. And the rate of mutation is more than a curiosity: Seeing how

many mutations separate us from cousin species and multiplying that

by the rate of change is one way scientists measure the time since we

diverged from each other—a “molecular clock.” So that new,

lower mutation rate—30-50 changes per generation—implies that our

common ancestor with chimps was not 5 million years ago, as had been

thought, but 7 million years. (For

a fascinating look at the question of how we measure human mutation

rates and how they affect our understanding of the past, check out

this

post by

anthropologist John Hawks.)

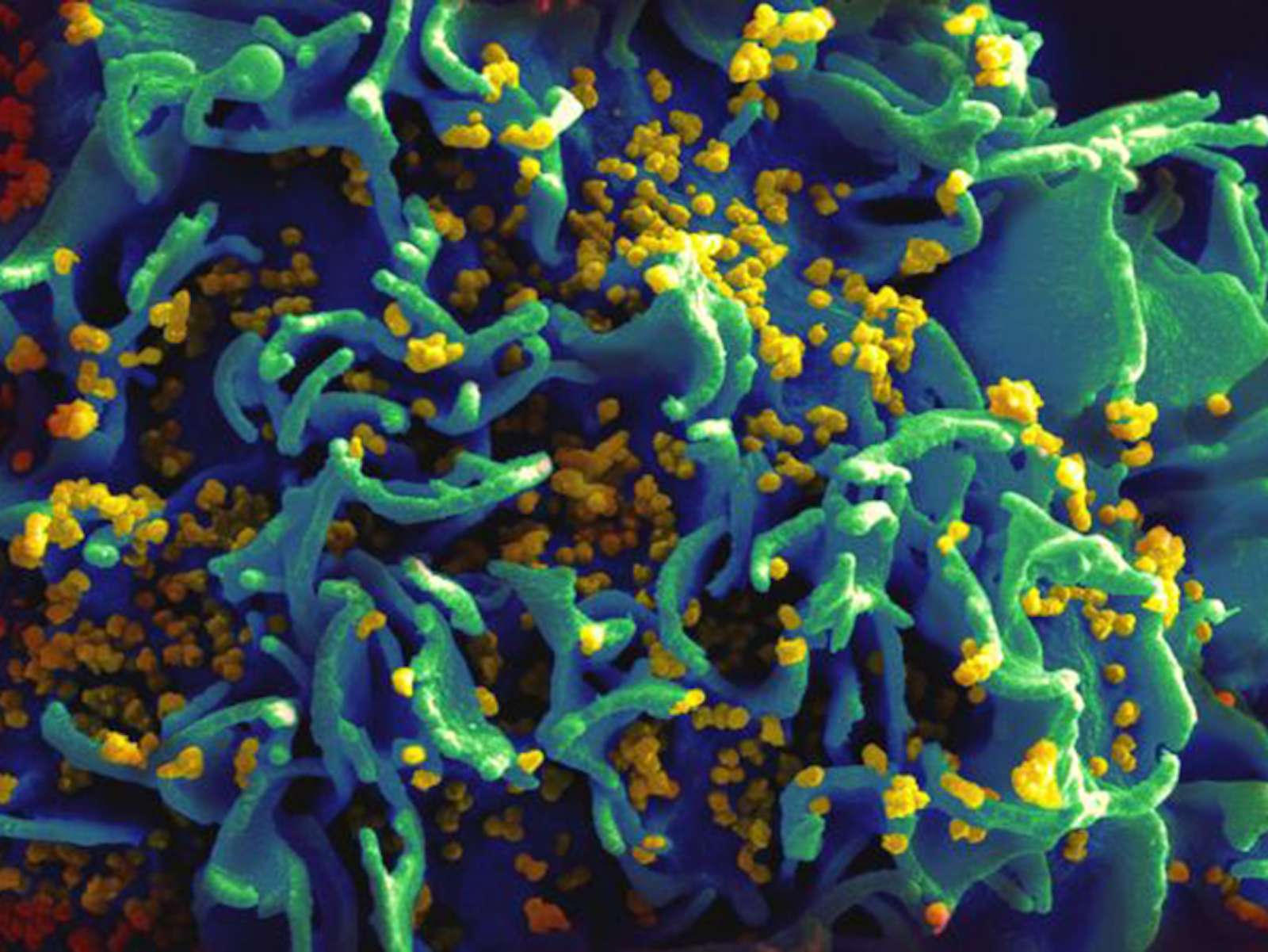

Viruses,

to the chagrin of the hosts they infect, have the highest

mutation rates around. They don’t have cells—just protein shells

packed with genetic material and little else—and it’s debatable

whether they’re even alive, yet they use similar machinery to

propagate. And they make mistakes constantly when fabricating new

copies of their genetic material for their daughter viruses, with

mutation rates up to 20,000,000 times higher than in humans. (Up to

about 10-3 to 10-5 per base per generation in viruses,

as compared to humans’ 5

x 10-11 per base per replication.)

These mistakes doom a certain portion of them but also allow for

extremely fast evolution: When the piled-up mistakes change the virus

enough so that it becomes invisible to a host’s immune system, it

can hack its way into our cells and reproduce in enormous numbers.

This fast evolution is why you need a fresh flu shot every year, and

why we don’t have a cure for the common cold. It’s why you can’t

predict whether an individual will progress from HIV to AIDS, even

when they are teeming with viruses, a study published last year in the Proceedings

of the National Academy of Sciences

suggests. In the computer model used by the researchers, individuals

with identical genetic backgrounds can have vastly different disease

outcomes—developing AIDS or not—because of random, chance

mutations in the virus. These imaginary people’s genetics were

similar to those of patients who often, but not always, manage to

avoid developing AIDS, and the study helped explain why even having

good genes can’t always save you: randomness is at work.

It’s

a messy, uncertain world on the cellular level, and it can have grave

consequences: Because of these tiny changes on the microscopic scale,

we don’t know how what flu virus will mutate and jump to humans,

and we don’t know who will develop AIDS and who will live to a ripe

old age with HIV. The messiness of mutation is also part of why we

can’t know what species, including our own, will be like millennia

from now. We’ll just have to wait and see how the future unfolds.

Veronique Greenwood is a former staff writer at DISCOVER Magazine. Her work has appeared in Scientific American, Popular Science, and the sites of Time, The Atlantic, and The New Yorker. Follow her on Twitter here.