One May day five years ago, an ambulance arrived for me. My eyes were twitching, hands shaking, thoughts racing and confused. At that point, I hadn’t slept for three days. I’d taken drugs, fell asleep at the wheel, bumped into a car at a red light. I was closer to suicidal than ever, but I wasn’t sad. Instead, I was agitated, frantic, paranoid. What put me at risk was not sorrow, per se, but loss of control: the careless apathy that might swerve a bike into traffic. My therapist convinced me I needed help. A phone call later, the ambulance took me to the mental hospital, where I stayed for a week and left with lithium.

Animals change with the spring. Bears come out of hibernation, dogs go into heat. Geese migrate. Humans? We go crazy. Spring is the season with the most yearly suicides, manic breakdowns, and involuntary mental hospitalizations. A psychiatrist I know calls mid-April “the witching hour.” That’s when his manic patients quit sleeping and start chattering away.

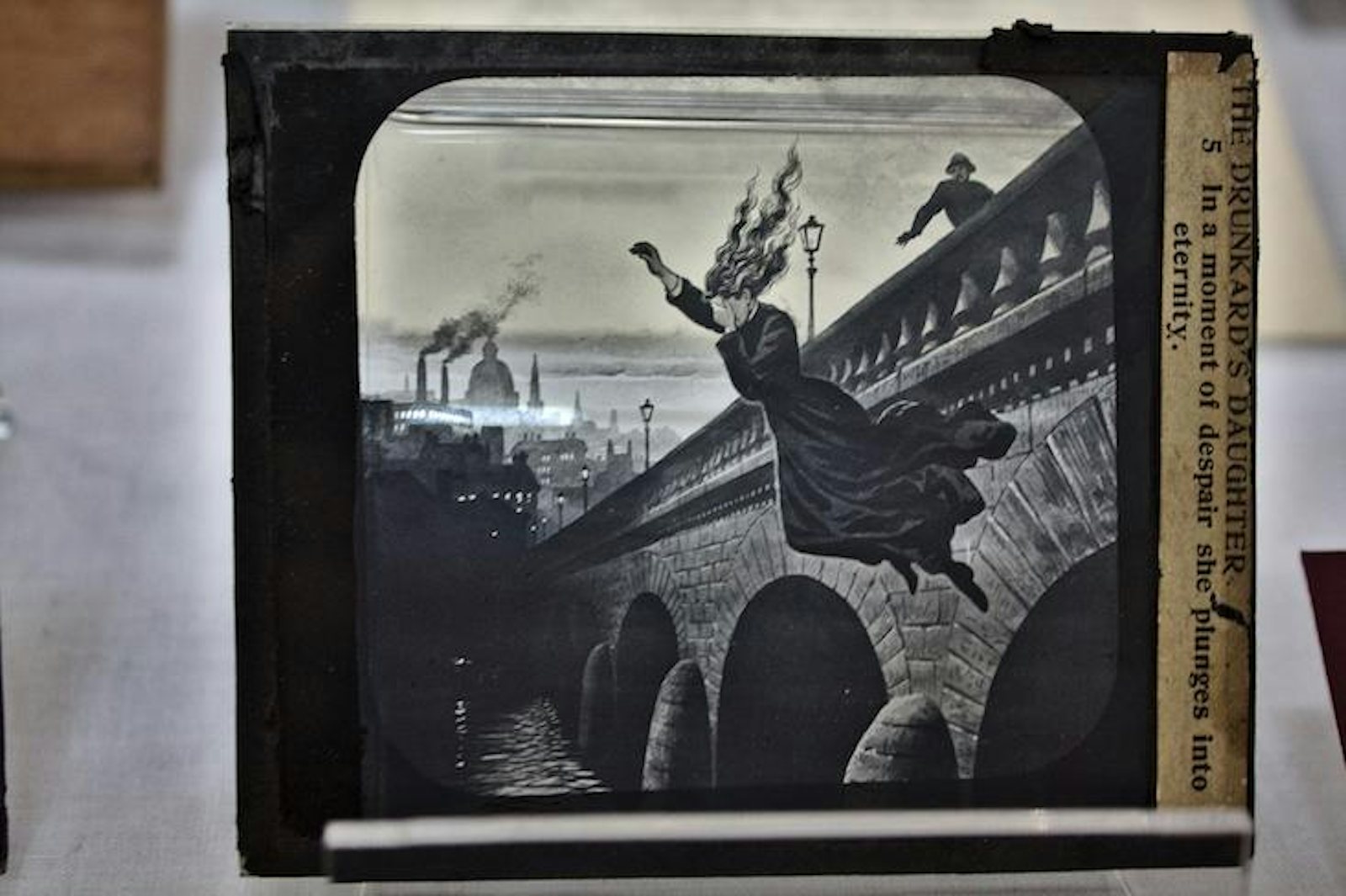

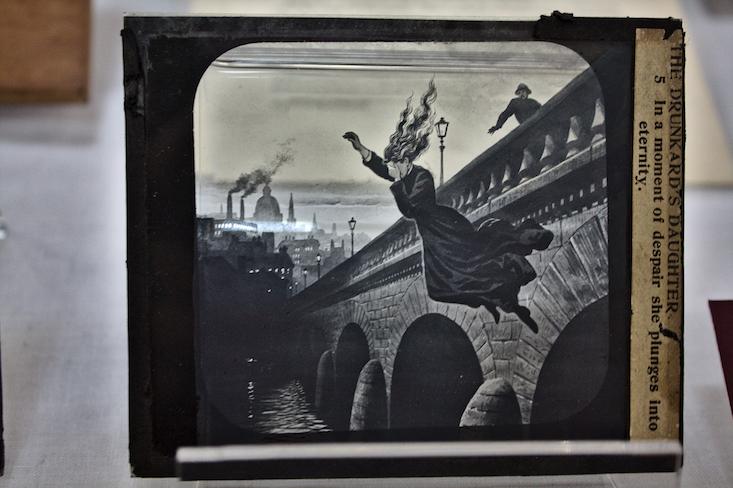

The evidence that suicides peak in spring, replicated many times, is especially striking in one study from Scandinavia. It looked at everyknown Danish suicide from 1970 to 2001, using Denmark’s state-maintained death registry. The data showed a dramatic surge between March and June, particularly for people with a history of mental illness. There were also smaller upticks in mid-summer and fall. The fall peak exists primarily for women, and for “non-violent” suicide—by poisoning, for example, as opposed to gunshot, hanging, or jumping from a bridge—and may relate to the time when children go back to school.

The pronounced spring peak in suicide risk, according to one theory, may result from sunshine’s effect on the brain. In mood disorders, especially bipolar illness, the circadian clock ticks out of synch with daylight. Melatonin, a hormone released by the brain’s pineal gland at night, encourages sleep but is suppressed by the sun. Melatonin levels begin increasing around 9pm and fade by the time we get to work in the morning. But these rhythms may cycle too quickly during mania or slowly during depression, leaving people alert at night when they should be sleepy. When melatonin goes up, so does serotonin, a neurotransmitter associated with mood and aggression. In April, the return of sunny days may act as a “precipitant,” as psychiatrists say, on a suicidal brain predisposed to impulsiveness. As to exactly how, the jury is still out.

The people “best” at suicide are known for upbeat moods and energetic drive.

The trend of spring suicide is notable because, among other things, it seems to reveal something about the nature of all suicides: Namely, that suicide has less to do with depressed mood than it does with agitated energy.

Depression is the most common mental illness, affecting some 30 percent of people at some point in life. Yet less than 5 percent of depressed people try to end their lives. What’s different about the ones who do? Apparently an aggressive loss of control.

In a 2005 review, titled “Dissecting the suicide phenotype: The role of impulsive-aggressive behaviours,” Gustavo Turecki, an expert on suicide at McGill University, argues that impulsivity is a crucial aspect of suicide. We are less likely to kill ourselves for a particular reason, than when we lose reason altogether.

“Impulsive-aggressive traits are part of a developmental cascade that increases suicide risk,” across disorders from depression to bipolar, schizophrenia to alcoholism, Turecki writes. “We all have levels of impulsivity. We may buy things without thinking, things we don’t need. But those people who tend to do this more frequently, and have a history of being a bit more aggressive, are more likely to die by suicide,” he says.

Bipolar disorder is a mental state that is prone to suicide exactly because it tends toward those qualities. Bipolar patients kill themselves at a rate higher than anyone else. (Next are schizophrenics.) What makes bipolar deadlier than depression, it seems, is this cocktail of aggression and impulsivity mixed with hopelessness. In the state called “mixed depression”—an agitated jitteriness with depressed mood—bipolar patients in a Finnish hospital were 65 times more likely to attempt suicide than when stable, one study found. Patients with classic depression were just 25 times more likely. When in a melancholic phase, however, bipolar patients were no more likely to try suicide than those with severe classic depression. Only when agitated by mania did their suicide risk spike.

The people “best” at suicide, then, are known for upbeat moods and energetic drive. Sleepless, manic patients sometimes go on impulsive sprees of shopping, sex, and socializing, or launch ambitious projects. Their most conspicuous trait is not an emotion but restlessness: agitated by constant curiosity or irritability, they don’t sit still. Their eyes keep moving. Bipolar II in particular runs a higher risk of those dangerous mixed states, and accordingly, of suicide.

Come spring each year, some bipolar patients raise their lithium dosage. Their doctors know that spring brings agitation. And it is specifically agitation that the drug works to block. Lithium is the most effective anti-suicide agent known. It tamps down suicide risk by 60 percent compared to placebo, a 2013 paper showed, not only in bipolar but in major depression. By restraining impulsive aggression, the researchers concluded, lithium might be used to stop suicide not only in patients with mania, but those with any mental illness.

“People who respond to lithium have a very rapid decrease in the pressure to kill themselves, in young people in particular,” says Antontello Preti, an Italian psychiatrist and an expert on suicide at the University of Cagliari. “They [may] still say, ‘I see no reason to live.’ But they won’t try to kill themselves. It’s like lithium is switching some kind of button.”

Taylor Beck is a writer based in Brooklyn. Before writing, he worked in brain imaging labs studying memory, sleep, and aging.

WATCH: The therapeutic value of reliving traumatic memories, according to the psychiatrist and neuroscientist Rachel Yehuda.