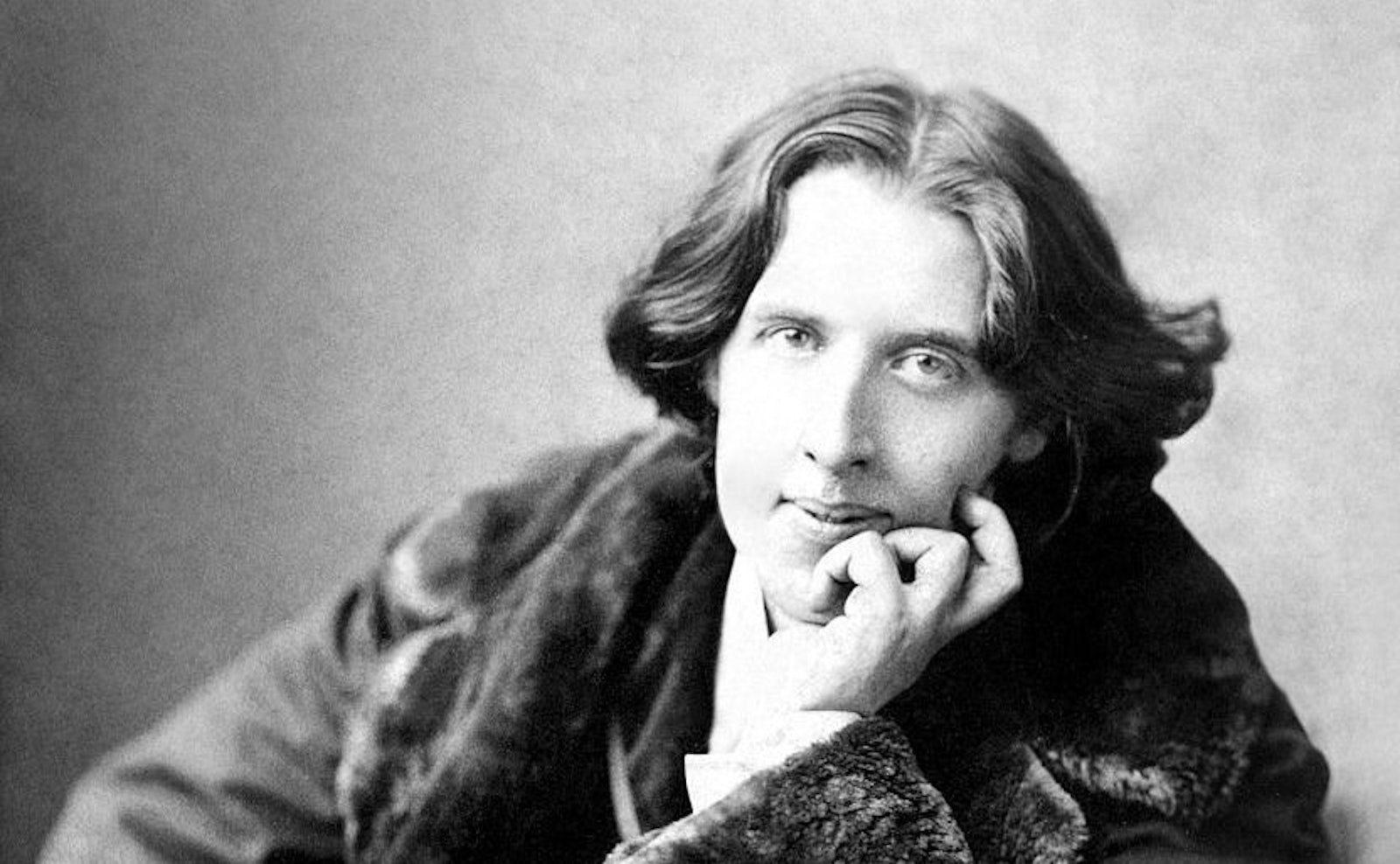

Oscar Wilde, the famed Irish essayist and playwright, had a gift, among other things, for counterintuitive aphorisms. In “The Soul of Man Under Socialism,” an 1891 article, he wrote, “Charity creates a multitude of sins.”

So perhaps Wilde wouldn’t have been surprised to hear of a series of recent scandals in the U.K.: The all-male charity, the President’s Club, which raised money for causes including children’s hospitals through high-valued auctions, was forced to close after the Financial Times uncovered sexual assault and misogyny at its annual dinner; executives of Oxfam, a poverty eradication charity, visited prostitutes while delivering aid in earthquake-stricken Haiti, and were allowed to slink off to other charities, rather than being castigated for their actions; and ex-Save the Children executives Brendan Cox and Justin Forsyth stepped down from their roles at other charities, after allegations of sexual harassment and bullying toward junior female colleagues resurfaced.

You might wonder how people who seem so good by occupation could be so bad in private. The theory of moral licensing could help explain why: When humans are good, it says, we give ourselves license to be bad.

In a recent paper, economists at the University of Chicago reported that working for a socially responsible company motivated employees to act immorally. In one experiment, people were hired to transcribe images of short German texts and paid 10 percent upfront, with the remaining payment being delivered if they completed the transcriptions, or if they declared the documents too illegible to transcribe. When they were told that, for every job completed or marked illegible, 5 percent of their wages would be donated to Unicef’s educational programs, the instances of cheating rose by 25 percent, compared to where no charitable donation was offered. Cheating manifested in both workers not completing jobs (taking the 10 percent upfront fee and running) and also workers saying that documents were too illegible to transcribe (and so receiving the full fee).

“The share of cheaters [was] highest when we frame corporate social responsibility as a prosocial act on behalf of workers,” the researchers, John A. List and Fatemeh Momeni, found. When the workers felt a greater sense that their own actions would lead to charitable donations, like Robin Hood, they in turn felt enough license to steal, essentially, from their employer to give to charity. “The ‘doing good’ nature of [corporate social responsibility] induces workers to misbehave on another dimension that hurts the firm,” List and Fatemeh concluded.

When humans are good, we give ourselves license to be bad.

A parallel might be drawn between the transcribers cheating in order to give more money to charity, and the organizers of the male-only dinner hiring hostesses for titillation, in order to increase the appeal of the event and drive up donations. But there are problems using this theory to explain instances of sexual assault. Moral licensing only applies when the bad behavior can be self-rationalized as good—or, at least, ambiguous.

In a 2011 study, researchers at the University of Oklahoma asked students to complete mental math tests on a computer, simple arithmetic problems only involving numbers one through 20. They were told that they would be shown a math problem, and needed to press the spacebar to bring up the response box. If they failed to do that quickly enough, the answer would automatically appear, ostensibly due to a bug in the computer program, still in its piloting phase.

Students were given either 10 seconds or 1 second to press the spacebar, on the working assumption that, while students who failed to press the spacebar in 10 seconds were deliberately cheating, those who failed to press the spacebar within 1 second, could “rationalize their failure to do so as incidental rather than immoral.” After the test, the students were then asked how many times they had failed to press the spacebar quickly enough, thereby seeing the answer. The prevalence of lying was significantly higher amongst the 1-second group.

But generalizing that moral licensing only occurs when bad behavior can be “rationalized” or “prosocial” overlooks the nuance of moral license theory, argues Daniel Effron, of the London Business School, who specializes in organizational ethics. “There are two versions of moral licensing theory,” he says. “One is the ‘moral credentials mechanism,’ which is more to do with rationalization. Basically it states, ‘I’ve done some good stuff. I’ve shown that I’m a good enough person. Now I can act ambiguously, because, as a good person, I know that my behavior is more likely to be good than bad.’ The other is the ‘moral credits’ mechanism, which works like a bank account. You do good stuff, you put a deposit in your bank account. You do bad stuff, you take a withdrawal. In that case, the bad deeds don’t have to be rationalizable.”

The latter version explains—though, obviously, does not excuse—the bad actions of Forsyth, Cox, and company. They had built up enough “moral credit” to justify taking some withdrawals, at least in their minds. This isn’t to say that the theory can determine or predict whether a good action will lead to bad behavior, Effron says.

He also stresses that the “charity sector isn’t any more vulnerable” to instances of moral licensing than any other sector. Humans are very good, he says, at finding reasons to be bad and making “mountains of morality out of molehills of virtue.” Studies have shown that trivial acts, including buying environmentally friendly cosmetics, can give consumers a moral license to behave badly. But, he adds, “You could make the argument that in the charity sector, you don’t have to work as hard to find your moral license for being bad.”

Abbas Panjwani is a journalist at Full Fact, the UK’s leading fact-checking charity. He has previously written for the Sunday Times. Follow him on Twitter @abbas_panjwani.