People may call cancer cells all sorts of derogatory names, but homebody isn’t one of them. Born into tumor cells, they relocate to surrounding tissues when their original homes become a toxic mess under the stress of their own overcrowding, the assault of chemotherapy, or when conditions elsewhere seem better.

Some oncologists characterize the process of cancer’s spread throughout the body—called metastasis—as a kind of diaspora. And since 90 percent of cancer mortality involves some degree of metastasis, the details of the journey may help researchers strategize against the affliction. “In cancer circles, there’s a kind of dogmatic view: Here’s where cells start and end,” says Bruce Robertson, an ecologist at Bard College in Annandale-on-Hudson, New York. But this perspective ignores many factors along the way. “By studying the movement of animals across landscapes, we know how organisms interact with their environment,” Robertson says, “and that holds true at the cell level.”

Together with Kenneth Pienta, an oncologist at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore, Md., Robertson describes metastasis in terms of human diasporas. For one, just as remnants of people’s homelands remain embedded in their identity long after a move, cancer cells never fully melt into their new surroundings. For example, in breast cancer, cells from an initial tumor will carry the genetic fingerprint of the original locale after they migrate to bone tissue. Identifying these cells in their new homes might help oncologists target them specifically with toxic drugs while leaving normal cells unscathed.

Secondly, in a diaspora, people often move to places previously scoped out by their compatriots so that neighborhoods don’t feel entirely foreign. Cancer cells similarly appear to beckon to other cancer cells, by secreting chemicals like cytokines and growth factors that mobilize and recruit cancer cells to future sites of metastasis, Pienta writes.1

These homing signals might be used to lure cancer to slaughterhouses. In a June issue of Future Oncology, investigators describe how chemical messengers in the nervous system, called neurotransmitters, might attract brain cancer cells to a location where drugs, radiation, or surgery could be safely concentrated.2 Cancers that spread quickly, like small cell lung carcinoma, will likely be the best targets for this approach of attract-and-kill instead of search-and-destroy.

Researchers applied a related approach to viruses in 2007, by creating “virus traps” out of bacterial cells. Normally, a virus invades bacteria by grabbing onto hair-like appendages, or pili. But in this case, the cells had the wrong sorts of pili, and the viruses flocked to the cells, but died before they could enter. While the initial experiments were run on viruses that attack bacteria, researchers are trying to adapt the technique to HIV by decorating cells that HIV cannot infect with proteins that attract the virus.

Although cellular snares have only been tested in petri dishes, researchers employ traps that take advantage of organisms’ innate urges in other contexts. For example, on Guam, wildlife managers plan to rid the island of invasive brown tree snakes by baiting them with dead mice stuffed with acetaminophen, the active ingredient in Tylenol and paracetemol that is toxic to snakes. “By looking at cancer from an ecological perspective, we can start to manipulate cues and the consequences of those cues to kill cancer cells,” says Robertson. In this case, the draw of home is the poison.

Katharine Gammon is a freelance science writer based in Santa Monica, Calif. who writes for Discover, Wired, and other outlets.

References

Pienta, K.J., Robertson, B.A., Coffey, D.S., and Taichman, R.S. The Cancer Diaspora: Metastasis beyond the Seed and Soil Hypothesis. Clinical Cancer Research 19 (21), 5849-5855 (2013).

Dennehy, J.J., Friedenberg, N.A., Yang, Y.W, and Turner, P.E. Virus population extinction via ecological traps. Ecology Letters 10 (2), 230-240 (2007).

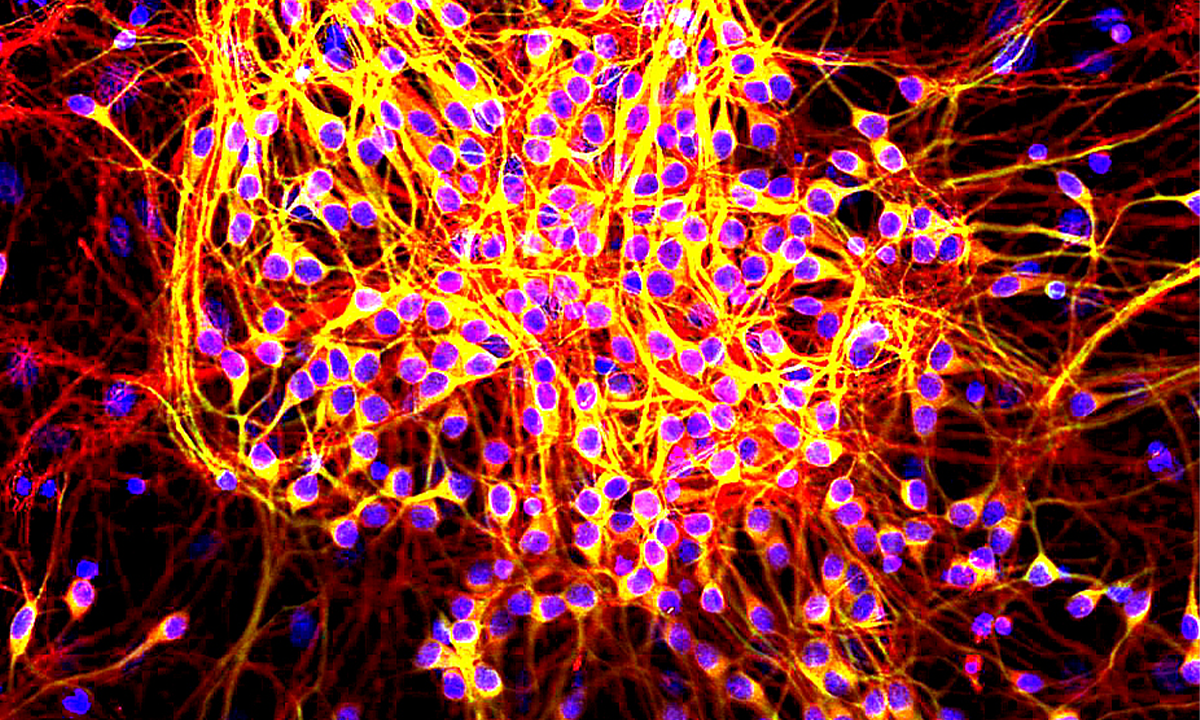

Lead photo by Kuruganti G. Murti, St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital; Courtesy of Nikon Small World.